Father Figure

Russ Sullivan, BA '83, doesn't like to sit still.

In more than 20 years of work in Washington, Sullivan has built a life in politics, succeeding on Capitol Hill as staff director of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee and then as a partner in McGuireWoods, a prominent D.C. law firm.

At the same time, he's sown the seeds of a different legacy.

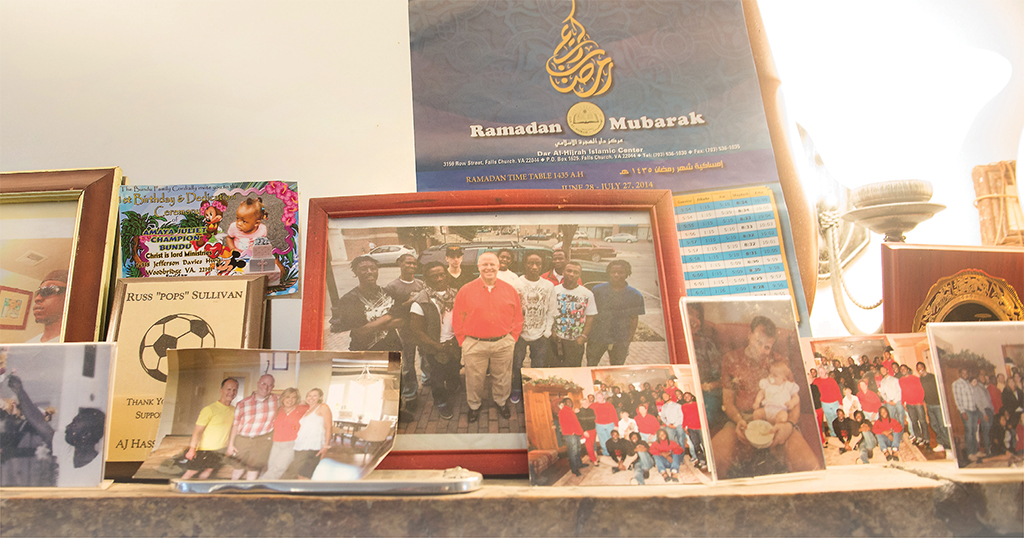

The 53-year-old has served as legal or designated guardian to 19 at-risk teenage boys, half of them from African countries such as Sierra Leone or Ghana. More than a dozen other youth know him as Pops and look to him as a mentor.

And now--at the urging of those young adults and with their help--he's raising three young brothers who lost their mother to cancer.

"For most of us, he's kind of that one rock in my life that I can count on," says Hussein Yusuf, 23. "To have somebody like Russ come in and take his time and be a father figure to us was amazing."

Yusuf, like many of his friends, grew up with a single mother working two jobs. "Nothing's guaranteed," he says--not where you live or whether you'll stay at the same school. "It's like the ocean waves moving back and forth, but Russ is like that one rock."

You get the sense of what Yusuf means as Sullivan talks of his days, of a whirl of texts, calls, visits: helping a 20-something in Arkansas figure out a car situation so he can keep an internship, waking young people up in person to make sure they get to where they are supposed to be, checking the youngest boys' report cards, and more.

But at the first stop of this Saturday night, a car dealership, Sullivan settles into the office as if he has all the time in the world--considering a purchase from one of his older boys while schooling the youngest in real-life economics.

"How much do you think that car costs?" he asks the 10-, 11- and 12-year-old brothers. One guesses $100, another $250. "I wish," Sullivan's voice booms. "If it were any of those prices, I'd buy it right now!"

This is Sullivan, the teacher, finding in each moment a nugget to tease out, ask about, passing on some part of the world he knows to the young people beside him.

Time was one of the gifts he gave early on.

He moved to Washington at 27 and describes his first years as "typical young adulthood," focused on launching a career, building a network in D.C.

Always active in church, he carved out hours with area teens.

In neighborhoods where male role models, and sometimes white faces, were rare, Sullivan made time--for Bible studies but also for regular Saturdays of community service, nights of movies or bowling and trips to reward good grades or goals achieved.

By the time he turned 40, he had been a mentor for years and had helped establish a nonprofit, Capital Area REACH, to offer mentoring, community service opportunities and job training to local teens.

Along the way, he began giving his then-girlfriend advice on parenting her teenage son. At that time, the son's best friend, Sean Jackson, was living with an aging grandmother.

If Sullivan was so good at parenting teens, the girlfriend finally told him, why didn't he take Jackson and become his guardian for his last two years of high school?

"I learned that I did not know very much about parenting at all," Sullivan remembers.

He couldn't tell when Jackson was lying or telling the truth. On his 18th birthday, Jackson, who is now close to Sullivan and calls him dad, shook Sullivan's hand, said thank you and announced he was moving in with his girlfriend.

"It motivated me, actually, strangely, to try again, and do better," Sullivan says.

Sullivan believes in the power of perseverance, and it's marked his journey.

A love of politics, born in a second-grade mock election mirroring the 1968 presidential election, led him by sixth or seventh grade to be the yard sign coordinator for city council candidates in his hometown of Little Rock, Ark. When people asked for a sign, he would get on his bike, take it over and put it up their yard. Or, he would call a list of supporters to ask if they would take a sign.

He was elected student body president at Baylor. In 1982, Sullivan worked with then--Baylor President Herbert H. Reynolds to found Baylor Ambassadors, an organization dedicated to assisting Baylor in lobbying local, state and federal officials. (He continues to serve Baylor in a number of ways, including as a member of the Baylor Alumni Network Advisory Board and assisting with Baylor in Washington.) He organized student workers and volunteers for Welcome Week and spent a summer working for an Arkansas secretary of state.

But that only took him so far.

"I tried for like seven summers to come to Washington, D.C., to be an intern and failed. I never got a job," he recalls. "I tried to work at the finance committee two summers, failed. The job I eventually got (at a law firm) was the third or fourth one I had applied for."

In the face of challenge, Sullivan grew more determined. "I knew I would like the work if I got the opportunity. Also, I didn’t want to lose."

It's that strength he works to pass on to his boys, telling them that when things don't go according to plan "that's all the more important time to show that you can win, to stay in there, conquer, learn that you can actually make it work."

As staff director of the finance committee, Sullivan spent his days on billion- and trillion-dollar issues--becoming known for his hard work, for leaving his office empty and working alongside the assistants and interns.

Meanwhile, he was fine-tuning his skills as a parent. He set strict rules--including no cursing, a rule he also had for his staff at work--and encouraged them to improve their grades. Community service was a cornerstone, because it offers youth a different perspective on life while developing job skills such as project management and working in a team. And Sullivan worked right alongside them.

He pushed his sons and youth he was mentoring, such as Yusuf, to continue their education.

Yusuf, raised by a mother who had fled Somalia, still remembers the call he got from Sullivan the summer after he graduated from high school.

Sullivan's urging and incentives--like a ski trip for improved grades--had led Yusuf to up his grade point average from a 1.9 to a 3.0.

Yusuf had applied to schools, visited campuses with Sullivan and was accepted to Potomac State College of West Virginia, along with several of Sullivan's other kids.

But as the summer went by, Yusuf made no move to go. "I just didn't really see the possibility for me to do it," he recalls. "I didn't see myself being able to pay for it, my mom being able to pay for it."

Then Sullivan called and stepped in to help. He took Yusuf and others to campus, settling them in, paying for books and classes, and making sure the only thing the new college students had to worry about was their studies.

"There's helping, but for somebody to do that without asking anything in return," Yusuf says. "He doesn't want anything from you but for you to succeed."

Sullivan can be dogged in that.

"He'll keep working on it until you address whatever's bothering you," says son Abu Kamara. "He sticks on it. Even when you're trying to avoid the problem, he sticks on it. That's amazing. Most people would give up. 'Your problem is your problem.' He doesn't give up. It's like he loves that, the challenge."

Earning more to help pay for college was one of the principal reasons Sullivan left the Senate Finance Committee for McGuireWoods. At the time, he recalls, "I had 13 in college, and most of them needed my help to stay in school." In all, he has helped dozens cover the cost of higher education.

These are far more than financial arrangements. At the root of it, this is family.

Sullivan takes vans of boys to Arkansas each Christmas. Last year, 25 went. They stay with Sullivan's large extended family and fit in some community service in Little Rock.

He keeps up a daily flow of calls and texts. "I'd say about half of them I get a text from at some point during the day," Sullivan says.

And each Sunday, Sullivan gathers his flock at the Church at Clarendon, a congregation in Arlington. They eat lunch together, sharing the news of the week, seeing what the youngest boys have to say next.

Rashid Fullah remembers when he first met Sullivan and heard the constant urging to reach out to the other boys, to be a positive influence, to support each other. "I was like, 'Why? Why would I do that?'"

The more he saw Sullivan devote his free time to others, the more it became second nature. Fullah has given time to a dental clinic in Falls Church that assists low-income patients and pulled together a group to go to New Orleans to help rebuild after Hurricane Katrina.

When he got his nephew into football, Fullah did more than just make sure his nephew got to practices and games. He saw that his nephew's friends, also with single, working mothers, needed a way to get to practice, too.

Working with Sullivan and Capital Area REACH, he established a football dads program. Last fall, the program's young volunteers got 11 football players and nine cheerleaders to practices and games.

Mirroring his experience with Sullivan, those relationships grew. Fullah and others pick up youth from the program for church each Sunday. They have been asked to talk to their charges about schoolwork and to come to parent-teacher conferences.

When three brothers in the program lost their mother to cancer, Fullah was adamant. Sullivan should take in the young brothers. The older boys would help.

Today, the young brothers have a host of older ones, with Fullah and three others serving as mannies, or male nannies, taking them to school, to activities, putting them to bed and getting them up.

"We have an elaborate family structure that you won't find anywhere else," Sullivan says. "But it is the best thing for these kids. It is helping each one of us to grow, and we're figuring it out."

And Sullivan is at the center, balancing it all.

Ask him how, and he's got any number of answers. "I'm a good delegator," he says at one point. "I don't watch TV," he says at another.

On a Sunday morning, en route to wake up some of the boys in person for church, he comes around to the parable of the talents.

"Here I am, born in the United States of America, we're all 5s compared to the rest of the world. I'm fortunate enough to have a great job, buy a house, have extra places to live," he says. "I better be using the resources God has given me to impact the Kingdom."

He thinks of Pharaoh's daughter taking in Moses, one of the first foster kids. "I need to be responsible to raise the kids in a way that honors God, helps them become independent, honest, humble servants, strong but humble servants," he says.

And there's something else.

Sullivan recalls the impact of a single moment at a particular stairwell in a strip shopping center. "A big part of my life and perspective goes to that stairwell," he says.

One of his kids happened to ride by the shopping center on a bicycle shortly after a robbery in the stairwell and was arrested. He spent more than two years in jail and was nearly deported before the conviction was overturned.

"It cemented in my mind that so many of these kids just don't have the advantages that most Americans have," he says. "I've had points along the way with these kinds of incidents that renew my passion for going that extra step. That's part of what keeps me going."

For guardians or foster parents, the commitment ends once a youth turns 18.

Sullivan never saw it that way.

What I tell the kids is, from my perspective, if they want me to be their Pops forever, that's great. If they don't, that’s their choice," he says. "I'm willing to keep the relationship going."