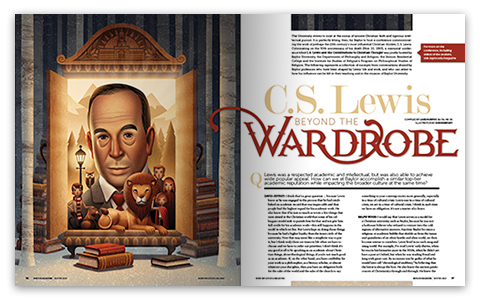

C.S. Lewis: Beyond the wardrobe

The University strives to exist at the nexus of sincere Christian faith and rigorous intellectual pursuit. It is perfectly fitting, then, for Baylor to host a conference commemorating the work of perhaps the 20th century's most influential Christian thinker, C.S. Lewis. Culminating on the 50th anniversary of his death [Nov. 22, 1963], a memorial conference titled C.S. Lewis and His Contributions to Christian Thought was jointly hosted by Baylor University, the Departments of Philosophy and Religion, the Honors Residential College and the Institute for Studies of Religion's Program on Philosophical Studies of Religion. The following represents a collection of excerpts from conversations shared by Baylor professors who have been shaped by Lewis' life and work, and who can attest to how his influence can be felt in their teaching and in the mission of Baylor University.

Lewis was a respected academic and intellectual, but was also able to achieve wide popular appeal. How can we at Baylor accomplish a similar top-tier academic reputation while impacting the broader culture at the same time?

David Jeffrey: I think that's a great question ... because Lewis knew as he was engaged in the process that he had established an academic record that was impeccable and that people had the highest regard for his academic work. He also knew that if he just so much as wrote a few things that were aimed at the Christian world that some of his colleagues would seek to punish him for that and not give him full credit for his academic work--this still happens in the world in which we live. But Lewis kept on doing those things because he had a higher loyalty than the inner circle of the university. Now that may seem like a simplistic way to put it, but I think truly there are times in life when we have to choose and we have to order our priorities. I don't think it's any good at all to be speaking as an academic about Christian things, about theological things, if you're not much good as an academic. If, on the other hand, you have credibility for your work as a philosopher, as a literary scholar, or almost whatever your discipline, then you have an obligation both for the sake of the world and the sake of the church to say something to your contemporaries more generally, especially in a time of cultural crisis. Lewis was in a time of cultural crisis; we are in a time of cultural crisis. I think in such time we have an obligation. It's not a matter of a choice.

Ralph Wood: I would say that Lewis serves as a model for a Christian university such as Baylor, because he was not a hothouse believer who refused to venture into the cold regions of alternative answers. Anytime Baylor becomes a religious or academic bubble that shields us from the issues and quandaries of an often hostile and alien world, we then become untrue to ourselves. Lewis lived in no such snug and smug world. For example, I've read Lewis' early diaries, when he was in his formative years in the 1920s, when he didn't yet have a post at Oxford, but when he was reading Freud and Jung with great care. By no means was he guilty of what he would later call "chronological snobbery," by believing that the latest is always the best. He also knew the ancient predecessors of Christianity through and through. He knew the Stoics inside and out. He knew the Greek classics quite well. And he studied them as a Christian. He believed that Christians are always called to set their faith in relation to all of the alternatives. So it's the range of Lewis' knowledge--and his ability to engage Christian and non-Christian things--that make him a model Christian scholar for us here at Baylor.

Tom Hibbs: Let me add that I think one of the ways we counter the tendency to have these two things separate from one another--the life of scholarship and addressing the sorts of questions that ordinary human beings ask at the most important moments of their lives--is by recruiting faculty who can do both, and by cultivating the kind of community amongst faculty and students where we aim to do both those things every day, and where the two things become not artificially connected, but organically and seamlessly connected, because we all are both scholars and human beings and human beings first and last.

What are the challenges facing Baylor as a Christian university today, and how do they compare to those faced by Lewis in his day?

David Jeffrey: One of the challenges for Christian universities today might be the relatively low order of hold that many of our students have on their own culture. I would say in particular their own religious culture. They come in often better educated perhaps in some technical ways than they were 20 years ago, but I suspect more poorly educated as Christians than they were 20 years ago and most certainly than 30 years ago. By that I mean that biblical Christians tend not to know the Bible very well. Liturgical Christians tend not to have attended church enough to really understand what the liturgy is intended to do. And almost all of them lack a sense of their tradition in the largest sense, Christian history in the largest sense. So, among us, Christian identity that has intellectual substance is not maybe what it ought to be, and that is a challenge.

Doug Henry: Many of our students grapple with a widespread cultural assumption that says, "Smart people outgrow God." Even when our students rightly reject such nonsense, they realize that serious-minded, theologically orthodox Christians are thought of as backwards, or naïve, or uninformed. In fact, one can find few places where skepticism about Christianity holds more powerfully than in America's elite universities. Intelligent, educated people just don't take "that stuff" seriously, where the stuff at stake involves two millennia of profound reflection on the triune God who creates and loves the world. In some cases, our culture retains certain Christian values, but in a way that largely deprives them of their supernatural moorings and their place within the biblical narrative. Our students may not always know the history of secularization or its scope, but they certainly sense its influence in today's culture.

Compounding our difficulties, many become vulnerable to the trend du jour because of a poor grounding in Christian intellectual traditions. Without deep understanding of our heritage, we risk being deprived of its riches without even knowing it.

We must face the cultural predicament posed by secularization courageously, knowledgeably, and patiently. From Baylor's founding until today we have offered an education that is deep, rigorous, given to serious questions, and open to honest criticism. All such things are possible precisely because we embrace a thoroughly Christian frame of reference.

David Jeffrey: I think in some ways the conditions we face are analogous to the conditions that Lewis faced in England 50 to 60 years ago. That is to say that we have a nominal civic Christianity in which at least some people know something about and have respect for the Gospel in its broad outlines, but there is 'nominalism' in their connectedness, which means they don't have much grip, necessarily, on the important things. Lewis had to take his radio audience in the 1940s to be not quite pagan, but pretty close--at very low levels of Christian formation--and as having a great deal of cynicism about the applicability of what little they knew to the real world. I think that's one parallel that might make the Lewis conference apropos.

Todd Buras: I agree with that. That's the connection I see in the conversations we are having here. The need of intellectually serious Christianity, given the cultural predicament that's been described, and the aim to provide that for our students, is something that I think we all feel very deeply. The role Lewis has played in pointing the way toward that kind of engagement in our culture is remarkable. One way to explain his status in broadly evangelical culture is that he was able to do that for a previous generation. And that's part of the reason why, at least for someone like me, he continues to hold that kind of fascination and what he did, the way he was able to represent his faith as a credible counter-voice to the popular culture, still seems to work pretty well in certain ways. There's a lot to learn from the way in which he succeeded.

Ian Gravagne: I would say all of these are excellent points and even amplified all the more when you look at the students and the faculty in mathematics, engineering and the sciences (STEM). Here the question of the Christian university is simply a question of relevance anymore. What does a Christian university have to offer in the realm of hard scientific evidence and mathematical proof? If that's the currency of your study and the currency of your research, where does Christian belief fit in? That's the level at which we have to have a conversation. But, Lewis speaks well into those questions. When I read [Lewis'] books with students who are engineers, they very quickly latch on to ideas that he wrote about, that still resonate.

For example, take the idea that Christ didn't come to say that he had the truth or that he was going to tell us the truth. He came to say that he WAS the truth. When they begin to really understand that fundamental statement, that little piece of Christian doctrine, and then connect that with the idea that they are part of this uncovering of truth in their study; when they do mathematics and science and engineering, they are uncovering truth in some way, that turns light bulbs on for them.

Lewis also writes in ways that are suggestive of a deep understanding of what it means to have a model, a concept of how something works that isn't that thing, but that represents it well. Of course mathematicians and engineers and scientists all have models of how things work that we know aren't reality, but help us to understand reality.

So there are lots of connections Lewis makes to the questions that concern STEM folks, but I suspect most students have never thought about them before. I enjoy coming along and using Lewis to say, "Here is why your faith is relevant to your work and your faith is relevant to teaching and learning in the classroom." God bless him for his ability 60 years after the fact to continue to be able to do that.

How significant was Lewis as a cultural influence, and how can we at Baylor carry that torch?

Alan Jacobs: One of the things that's not often enough noticed about the broadcast talks that Lewis did for the BBC, that later became Mere Christianity, is that they were wartime talks. When Lewis begins with this section called "Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe," he was speaking to an audience that was getting moral instruction and moral exhortation on a daily basis. That is, on the BBC all day every day, in signs they would see in their shops, they were being encouraged. The only sign we see today is "Keep Calm and Carry On," right? That sign was actually never released, interestingly enough, but there were a hundred others. It was an environment in which people were being told day by day by day, "Pull together," "Do your part," "Don't shirk," "Don't let the side down." That kind of moral exhortation was something they were prepared to hear because it was part of the wartime propaganda, not in a critical sense but a descriptive sense.

When the war was over and England entered into its post-World War II malaise, Lewis' influence in England declined precipitously. At almost exactly that same time he appears on the cover of Time magazine and then becomes enormously important in the U.S. So it turns out that while his message had a short-term effect in England, he lost that central place--except as a writer of children's books--in England, but, his reputation continued to escalate here in the U.S.

America proved to be more fruitful soil over the long-term than his native soil. There could be all sorts of reasons why it worked out that way, but over the long haul his influence in the U.S. absolutely dwarfs by orders of magnitude his influence in the U.K.

David Jeffrey: Lewis in America is almost always preaching to the choir. That is to say, his readership is already a Christian world, a Christian culture in America composed of Catholics as well as evangelicals and other Christians. Knowledge of his contributions as an apologist drops precipitously outside of that group.

But Lewis offers a model for something that's desperately missing in American culture--namely that we're always willing to buy wisdom at retail but seldom willing to do the wholesale work to get it for ourselves. This probably sounds like an extreme statement, but what I mean is this: Not only was Lewis a generalist of a sort that would be more permissible at Oxford or Cambridge in his day than here now, but that therefore he learned more. Lewis started as a philosopher, learned classical languages, went on to literature and so on, and then he could do theology with a kind of a range that is not often found here. We're not producing this sort of scholar in our culture. It's one thing to hold Lewis in awe for what he did and to be gratified to bask in the reflective glory of his intellectual life. It's another thing to encourage students such as are at Baylor right now to imitate his intellectual virtues, to pursue the languages, to get the philosophy, and to acquire the intellectual resources and tools that will enable them, by the time they are 55, to write something half so interesting as he wrote when he was 55. That's what we're not doing as well as we should.

There positively is a great challenge for Baylor, to try and educate our very bright students and to give them everything we can and then push them on toward that kind of a model. It may be that our culture is going to hell in a handbasket more quickly than England was in the '60s. So someone's going to have to do some reconstructive work, and part of that work, I think, has to be done by intellectual Christians for Christianity to have a salty voice in the 21st century in America. I don't think we should expect it will all be done by televangelists and even really good people working on the street corner.

Alan Jacobs: What I find myself thinking about as we have this conversation is a character in one of Lewis' novels. In That Hideous Strength, one of the two central characters is Mark Studdock. There's a passage about a third of the way into the book in which Lewis describes Mark's extreme vulnerability to manipulation--he pauses in the action and says, "It must be remembered that Mark had at his fingertips scarcely a scrap of genuine learning. The severities of a traditional humanistic education and a rigorous scientific education alike had passed him by. He didn't have either one. And, therefore, he was utterly vulnerable to rhetorical manipulation, as he just didn't have the intellectual equipment." It's interesting that the two words that Lewis uses are "severities" and "rigor." Those are interesting words. What Lewis is saying very clearly, is that if Mark had had either one, if he had had either a first-rate scientific education or a first-rate humanistic education, he would have been equipped to offer at least some resistance. But he had nothing. He always did well in "essays and general papers"--if he had the opportunity to bloviate he could sound good, you know? But that was really all there was to it. He was, Lewis says, a "hollow" man.

Not to be disparaging of our students, but we need to remember how little they know when they get here and how few "rigors" and "severities" that they have undergone, in order that we may educate them more rigorously, but also to be compassionate towards them and realize that they are not going to be able to catch up overnight. It's going to require a lot of patience from us to get them up to speed in these matters. But we do well to think of our students as being in many ways like Mark Studdock, beset on all sides by rhetoric from television, movies, the Internet,

even the books they read; they are getting buffeted by this stuff and they don't necessarily have what it takes to stand up straight in a gale like that. That's how I think of our job in a lot of ways.

Todd Buras: Baylor is trying to function as the salt and light in the world. There's a saying that I got, I don't know from where--maybe a class on politics--that "if you're explaining, you're losing." The things you've heard expressed here in the last few minutes, they are very complicated ideas about how the church engages the world--the academic world and the broader culture. It's a very complicated project and difficult to explain and communicate, in some ways its hard for me to pin down. But Lewis does the same sorts of things and people just get it. Why you would engage in this broader project that's been described, that's something that needs explaining; Why you would read Lewis' works, doesn't. That's interesting to me. That's one of the things I've noticed in the level of interest students are capable of mustering for conversations about Lewis, which I haven't seen them capable of mustering for any other intellectual subject.

There's something in his example that reflects a certain kind of hunger for intellectually credible and rigorous engagement of culture from the point of view of faith that people recognize--it's there, he did it well, and its something we all need to be doing.

Alan Jacobs: I do want to say, that probably the best teacher I had in graduate school was de-converted from Christianity by reading Mere Christianity. I think what happened was that its importance and ideal characteristics had been so magnified to him that he was expecting that this was the book that was going to solve all his problems, answer all of his questions; and when he read it and it didn't do that, the bottom just kind of dropped out from under his faith. Which means that we all have work to do, right? Lewis is not the universal solvent. He's not the answer to every question or the prescription for every disorder. And I think if there's a real failure that evangelicals and others who love Lewis have habitually had, it is using him as a crutch rather than seeing him as an example.

The real questions are "Can we do for our audiences what he did for his audience? Can we rise to that challenge?" And we probably can't do the range of things that he did because his range was unique, I think. Nobody else, no other Christian writer I can think of, has been successful in so many genres; but, we can all do our part within the scope of our competence and our expertise. The question is not "How do we get people to read Lewis?"--even though it's great to get people to read his books--but I also want to set as a challenge for myself: Can I do in my own limited way what he did? I've got to address American university students in 2013, not a BBC radio audience in England in 1942. So, what would be the corresponding thing for me to do here? I think that's what Lewis would have wanted. From 1945 on, he despaired that there were so few people who were taking up his mantle and trying to do what he did. He kept saying, "Other people can do it. I'm not the only one who can do this." He wanted to train people who would follow his example.

How are we doing as a Christian university? Are we teaching and training our students in appropriate ways?

Lori Baker: It's absolutely a teaching and training issue. Our students come in fundamentally Christian. They have strong Christian values. Some of my students study the Bible well; but when I say "Christian scholars" they automatically assume I'm talking about someone from the religion department. They don't imagine that that means across campus. One student that I've talked to...and worked with... she's an exceptional student, explained to me that she keeps her opinions to herself in classes when they contradict her Christian values.

And I said that there's no reason to do that within the academy. That's the whole point of your education. We're here to help you think through these deeper questions. If you don't express those, then the professor doesn't have the opportunity to discuss that further. So she's beginning to talk in her classes about things that she's developed in her own faith. Most of the students I have, often who have strong Christian convictions, have been indoctrinated in the idea that those convictions have to be kept separate, the life of the mind versus the soul, so they don't combine their intellectual life with their faith life. We talked about this with students before, but that's pretty fundamental and the second I say anything about being a strong Christian and learning about these ideas and readings, they just latch on and they're so excited to hear a faculty member talk about it.

Todd Buras: I think that the straight answer has to be that it's a very mixed bag. In some cases, things are going really well and students are finding themselves in the kinds of conversations that open their minds up and open their hearts up to see their faith in a new way--as something that animates the life of the mind and permeates the life of the mind instead of something totally on the side. I don't know that there's any one thing we can do to give students that sort of experience. I think that often happens by virtue of things faculty members say in class and in areas where the connections are very naturally. It also happens in the interactions students have with faculty outside of class in our residence halls and on mission trips and things like that. But it may not happen at all for some students--and that's why I say it's a mixed bag.

David Jeffrey: What I think is going on at Baylor owes to a growing recognition that you cannot create a meaningful form of discipleship, a meaningful form of life which can be called Christian, except by pooling the resources of those who are disposed to learn and to teach and to give their lives to that so that the entire community can benefit from it. Baylor has an idea of its role historically, which is, I think, really interesting. At one time, we put in this way: "This is the largest Baptist University in the world--a kind of guardian of Baptist culture."

One of the things that's true at Baylor now, that maybe wasn't so true even in our recent past, is we now think of ourselves as having a still greater responsibility. We have a responsibility to Christian culture more broadly conceived, not just Christian culture in the state of Texas or the United States, but in the world.

So one of the things that we've been doing is we've been bringing in faculty and students from a much wider range of backgrounds. We've been engaging churches from a wider range of denominations. We've been thinking about what Don Schmeltekopf, my predecessor in the provost office, called "big tent orthodoxy," as the kind of model that makes the most sense for the relationship of the Gospel to the world.

And we haven't imagined that the university solves all of the problems. It surely can't. But we have imagined that the university has particular resources which can be given to the church and given to others disposed to receive it. Whether they receive it merely as instrumental knowledge--or whether they get a formation which more broadly helps them to know and think like a Christian, that is, to think in the terms of the qualitative in learning, to put it in Lewis' terms, rather than the merely quantitative and informational--that remains a pressing question for Baylor's future identity as a Christian university.

Alan Jacobs: I believe the deep, rich resources of the broad tradition of Christianity--East and West, for 2,000 years--do not foreclose intellectual possibilities, but enable intellectual possibilities. I came to Baylor because I think people here believe that, too. This is a place where the leaders are, I think, saying to me and to others, "If you want to take advantage of the richness of that tradition in order to pursue serious intellectual inquiry and take major intellectual risks, then let's go for it."

Web extra:

How has C.S. Lewis impacted your sense of vocation as a Christian thinker, Christian writer, or Christian teacher?

David Jeffrey: I am old enough to have studied C.S. Lewis in a class at Wheaton College led by Clyde Kilby, who was a great friend of Lewis. He was arranging for me to go study there [Cambridge] with Lewis, but Lewis, of course, did not survive long enough for that to happen. But I'll always remember this class because it was vivid with the impact of a very fine mind expressing itself through several genres at once. Lewis wrote as a philosopher. Lewis wrote as a philologist. One of my favorite books is one I expect almost none of you have read, called Studies in Words. He wrote as a novelist, he wrote as a children's writer, he wrote as a theologian, he wrote wonderful essays in practical theology, he wrote as a critic of the educational system in The Abolition of Man. Everywhere you turn, Lewis was tackling a new genre and I had never met anyone like that before. He fired my imagination considerably. The way he has affected me is that he gave me an eye on the university, a view into the university in terms of what at its best it can be as a stimulus to wide ranging thinking informed by a Christian worldview; there's no question I got a great deal of that perspective from Lewis. At the same time he published an absolutely wonderful academic novel called That Hideous Strength, a terrific critique of the university; it was prescient, it was prophetic, it was telling us then about where we are now.

Ralph Wood: I wouldn't be teaching at Baylor were it not for C.S. Lewis. That sounds like a ridiculous claim but I can candidly declare that without his early influence on my life, I seriously doubt that I would be in this room at this hour.

In 1959 when I was 16 years old, I thought that I was meant to be a Baptist preacher. Some people still accuse me of having pursued that vocation under the guise of teaching. I accept the accusation gladly, though I also point out that it's because I've never found anyone willing to lay hands on me and, therefore, I am not ordained. I very much wanted to attend Baylor because Baylor was regarded as the Baptist Jerusalem on the Brazos. It's where every Baptist boy who thought himself called to ministry wanted to study. My pastor, an excellent Baylor grad, was my model. Yet my parents were public school teachers in a little backwoods town "behind the pine curtain," as we call East Texas, and they couldn't afford to send me, so I was not able to come to Baylor.

I attended a small and rather undistinguished state school where there was no department of philosophy, no department of theology. All I had was the Bible and Jesus, as it were, and I needed a lot more than that. And I so discovered C.S. Lewis as a freshman. And Lewis saved my life. He taught me that to be a devout Christian to the best of one's ability, and to be thinking as hard and clearly as one could about ultimate questions, were things that went together and were not meant to be divorced.

And so I went from Mere Christianity, the book which most people cut their teeth on, to the larger circle of Lewis books - the Problem of Pain, Miracles, even A Grief Observed. I had never even heard of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, so I soon read it and the other Narnia Chronicles. I gradually discovered that Lewis is probably at his best in such fiction as That Hideous Strength, which is part of his space trilogy. Thus did I begin to be convinced, under the influence of C.S. Lewis, that an unthinking Christian is a contradiction in terms. As a result, I have spent my entire career reading and teaching other serious Christian writers: C.S. Lewis and his close friend J.R.R. Tolkien, Flannery O'Connor and Walker Percy, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, G.K. Chesterton and Dorothy L. Sayers -- the true Christian heroes of the 20th century poetic and literary world.

In fact, I began my second year of teaching at Wake Forest in 1972 by devising a course very similar to the course called The Oxford Christians here at Baylor. There I teach not only The Screwtape Letters but also The Great Divorce and Till We Have Faces, because in all of these imaginative works, Lewis does not provide easy answers to difficult questions, so that if you have a doubt or if you find yourself in perplexity, you can go to the right page in Lewis in order to find the right answer. On the contrary, as Rowan Williams argues in his splendid little book entitled The Lion's World, Lewis opens us up to an imaginative realm of "supposals," asking what it would be like both the problems and the wonders that the children confront in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, and that other characters meet throughout the whole of Narnia. Thus does he provide us a questioning and challenging faith, not a formulaic one.

Tom Hibbs: When I was a freshman at the University of Maryland, I had in my first semester at this very large secular institution, three atheists as professors. They were not mean people, they were not trying to destroy students' faith, but it was a challenge that I had never anticipated and was without any capacity to respond to.

And one of the things that Lewis gave me ... [was] an example of a Christian who was fundamentally committed to an investigation of arguments in the pursuit of truth. And that was immensely important to me, to discover an author who provided a kind of model on how to do that.

The other thing I would mention touches upon what Dr. Wood was saying about the imaginative universe. I'm a philosopher by training who likes film and theater and the arts and has an opportunity to write some about that, and I think that Lewis is absolutely crucial. You know what's interesting is that one of the most lasting impacts of Lewis into our own time is, surprisingly, in the realm of theater. You've got this one-person play/performance of The Screwtape Letters, you've got even perhaps more prominently an off-Broadway play that's in New York and in Chicago called Freud's Last Session, which is a dialogue between a very elderly Sigmund Freud and a very young C.S. Lewis.

It strikes me that Lewis' strength in his fiction is sensed in The Abolition of Man, that what young people needed was the formation of the moral imagination that mediated between what he called our animal appetites and our spiritual intellect. This has struck me in my work on contemporary film as a really important contribution of Lewis and again, as an anticipation of how far the culture would in some sense go wrong. There are some good things in the culture, with respect to moral imagination, but I think we can all quite readily pick out the corrupting influences in the culture and Lewis thought this formation of the moral imagination was absolutely crucial to the secular and believer alike.

C. Stephen Evans: I want to say something about mere Christianity, not the book, but the concept, because the concept of mere Christianity was hugely important to me. I grew up in a fundamentalist church; it was a very sectarian kind of place, and we thought we were the real Christians. Reading Lewis taught me that Christ's body, the church, is extensive, both in time and all over the world, and that I had much more in common with other Christians than I ever dreamed. In saying this I have to be careful: mere Christianity is not itself a type of Christianity. It's not a denomination. And Lewis would be the first to say, you shouldn't be content with only mere Christianity; you always need some more specific home with a more full-fledged liturgical life and doctrinal views, and all that goes with that, and that's very important. But nevertheless, Lewis taught me that the people in each of the great streams of the Christian faith, whether they are protestants or catholic or orthodox -- the people who are real believers and who are serious about their faith -- are actually closer to the other people in the other streams who are also serious about their faith....

What Lewis really taught me, I guess, was how to understand the real essentials of Christianity. It doesn't mean nothing else is important. Some of the things we Christians disagree on are quite important, but nevertheless, Lewis wants us never to lose sight of what's essential, what we have in common.

Lori Baker: C.S. Lewis was great critic of scientism. When I say scientism, I mean the dogmatic endorsement of the scientific methodology -- inductive methods of the natural sciences being the only way to obtain factual knowledge and to describe true knowledge about man and society. So while I'm a scientist and I do reduce things quite often in the work that I do, I acknowledge that there is the propensity for science to go outside its proper boundaries, and Lewis was concerned that the power of science would be abused, and indeed it can be and has been.

In That Hideous Strength, the character Lord Feverston reveals the real purpose of N.I.C.E., the National Institute for Coordinated Experiments, to the young sociologist Mark Studdock, who he is recruiting as a propagandist for the cause:

"If science is really given a free hand, it can now take over the human race and recondition it; make man a really efficient animal. The question of what humanity is going to be, is going to be decided in the next 60 years. Man has got to take charge of man. That means, remember, that some men have got to take charge of the rest. You and I ought to be the people who do the taking charge, not the ones who are taken charge of."

Lewis' views on scientism really connect with my own on this point. He lived during World War II and he saw first hand what the Nazi army did: the ability of men to take over using science, the will, the appropriation and the exertion of power over other men. I see a lot of Lewis' work focused on the idea of some taking the power of others. I think he's talking about each generation's power over its successors. If we look at modern science today and the power that we have over subsequent generations, the power that we have to make scientific decisions that have moral consequences each day is overwhelming. ... I find Lewis somewhat prophetic in his ability to call us out when we give science undue reign.