Learning to Fight

Baylor University and the Baylor College of Medicine's (BCM) National School of Tropical Medicine (NSTM) work together to fight neglected tropical diseases that prey on the world's most vulnerable.

Dr. Peter Hotez recognized a problem, a lack of recognition problem.

When the United Nations launched a series of health-related development goals in conjunction with the turn of the calendar in the year 2000, Hotez noticed that the diseases he dedicated his life to fighting — diseases that prey on the world’s most vulnerable — were lumped together and branded as “other diseases.”

“I realized then,” Hotez says, “that if we’re ever going to really solve these problems, we’re going to have to stop calling them ‘other diseases’ and brand them together as a group that’s every bit as important as HIV and AIDS or anything else.”

Nearly two decades later, these “other” diseases are known as neglected tropical diseases. Baylor University students and faculty are willing partners in the fight against the neglected tropical diseases. They are united by a shared mission, raising up a new generation of health leaders to serve, heal and render the word “neglected” as no longer accurate.

The growing academic partnership between Baylor University and the Baylor College of Medicine’s (BCM) National School of Tropical Medicine (NSTM) takes on multiple forms. For BU students, it is most readily experienced through a two-week summer immersion with the world’s top tropical disease experts inside lecture rooms and labs at the Texas Medical Center in Houston. The NSTM Summer Institute Program began in 2014 and has since welcomed about 20 to 25 students each summer to participate in an intensive program designed to introduce them to the opportunities and needs around them.

“If we’re ever going to really solve these problems, we’re going to have to stop calling them ‘other diseases.’”

Neglected tropical diseases consist of 17 common chronic parasitic and infectious diseases — maladies like Chagas disease, hookworm, Zika and Ebola. They are most acutely felt in areas where residents are least able to receive treatment. More than 1.4 billion people live below the World Bank’s poverty level of $1.25 in U.S. currency per day. Nearly all of them, collectively known as the “bottom billion,” suffer from at least one of the 17 diseases. The name “tropical disease” belies the fact that they can be found anywhere, including in the United States. Nearly 20 million Americans live in impoverished conditions, and nearly 12 million of them suffer from these diseases.

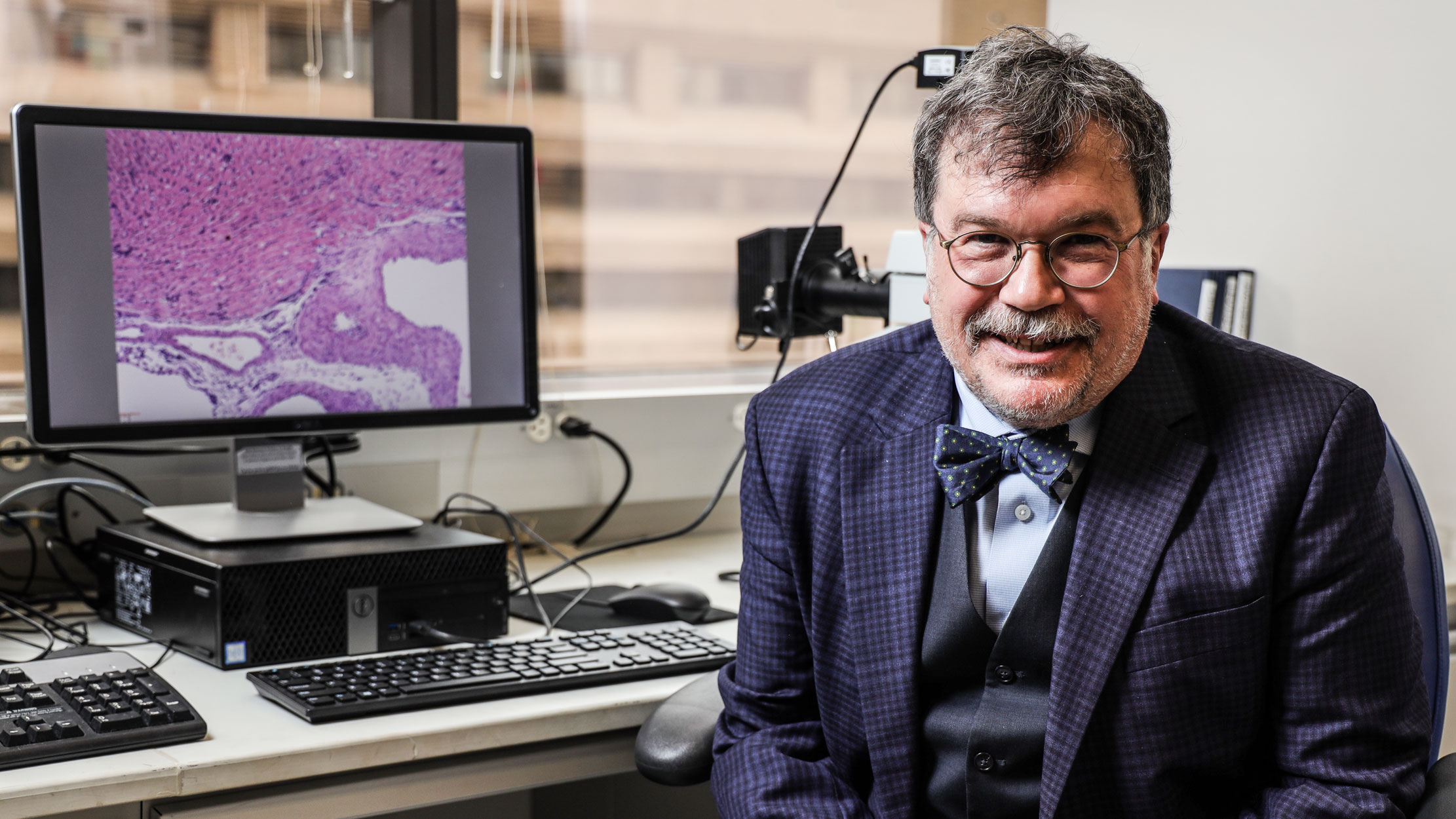

, National School of Tropical Medicine dean, Baylor College of Medicine professor, University Professor at Baylor University, and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

“These diseases are first and foremost the diseases of extreme poverty,” Hotez says. “They’re also a stealth cause of poverty. Wherever you see extreme poverty, that’s where you see them.”

Hotez is NSTM dean, Baylor College of Medicine professor, University Professor at Baylor University, and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development. He is a leading international expert and activist on topics of tropical disease and vaccine development. Hotez says the causes for the relationship between poverty and these diseases are many.

“We don’t understand exactly why,” Hotez says. “Is it poor quality housing? Absence of window screens? Is it environmental degradation around homes with discarded items that breed mosquitoes?”

The answers can be all of the above and more. That’s why, as students discover, they have to be multidisciplinary detectives in many ways — first understanding the sociology, housing, communication and culture of a place to more fully understand how diseases spread in different areas, and how to address them.

It is a formidable challenge, one that sears the conscience of students like Brian Adjetey, a sophomore business fellow from Corpus Christi, Texas, who participated in the Summer 2019 Institute.

“It opens your eyes,” Adjetey, a first-generation American whose parents emigrated from Ghana, says. “So many factors play into these diseases. Oftentimes, people want to help, but there’s so much to think about, like basic health infrastructure that not everyone has access to. There’s so much need, and learning about these diseases motivates you to want to learn even more and improve your own understanding and your own skills so that you can help.”

For Baylor University and Baylor College of Medicine, the roots of the Institute partnership extend beyond a shared name more deeply into a shared sense of mission. In the medical field, tropical medicine is far from the easiest path. The quest to cure and the desire to learn often lead tropical medicine professionals into places where sanitation, pollution and disease are constant concerns.

Tropical medicine, likewise, remains far from the most lucrative medical career path. Medical advances driven and vaccines created by tropical medicine professionals won’t be featured on Super Bowl commercials, and the people who benefit from them can’t pay for them. The field calls for people whose compassion overrides their desire for ease, and Baylor University is a place where such young people exist.

Hotez and his team joined Baylor College of Medicine to form the NSTM as the only school in North America whose sole focus is the understanding and eradication of tropical disease. They were soon thereafter introduced to Baylor University students whose enthusiasm for the work caught their attention.

“After we came to Houston in 2011, we began getting queries from Baylor University students in Waco because so many of them go abroad as a part of Christian mission trips,” Hotez says. “They were going to various countries around the world but recognized they wanted more of that framework around global health to understand everything that they’re seeing. As I met them, I was so impressed with the quality of these Baylor University undergraduates. They’re so enthusiastic and overwhelmingly kind.”

Dr. Maria Bottazzi, NSTM associate dean and professor, Distinguished Professor of Biology at Baylor University, and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

Hotez’s longtime colleague is Dr. Maria Bottazzi, NSTM associate dean and professor, Distinguished Professor of Biology at Baylor University, and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development. Bottazzi noticed a strong missional component almost immediately.

“The mission of Baylor as a university is quite distinctive,” Bottazzi says. “Already the student body, as well as the faculty and University leaders, have a drive for serving the world — the missionary interest. So that prepares the students we receive to work closely with Baylor College of Medicine. We have the same drive.”

The NSTM was born from those initial meetings. The partnership has grown to include collaboration between faculty members in Waco and Houston, but it was driven by students.

Dr. Rich Sanker, senior director of prehealth programs and undergraduate research in Baylor’s College of Arts and Sciences, says he sees a global interest among this generation’s students.

“They are predisposed to want to serve and lend their talents abroad,” Sanker says. “It was a natural fit for us to partner with NSTM on this program to empower them to enhance their abilities, cultivate their skill sets and awareness, and develop in service in meaningful ways.”

INTENSIVE FOCUS

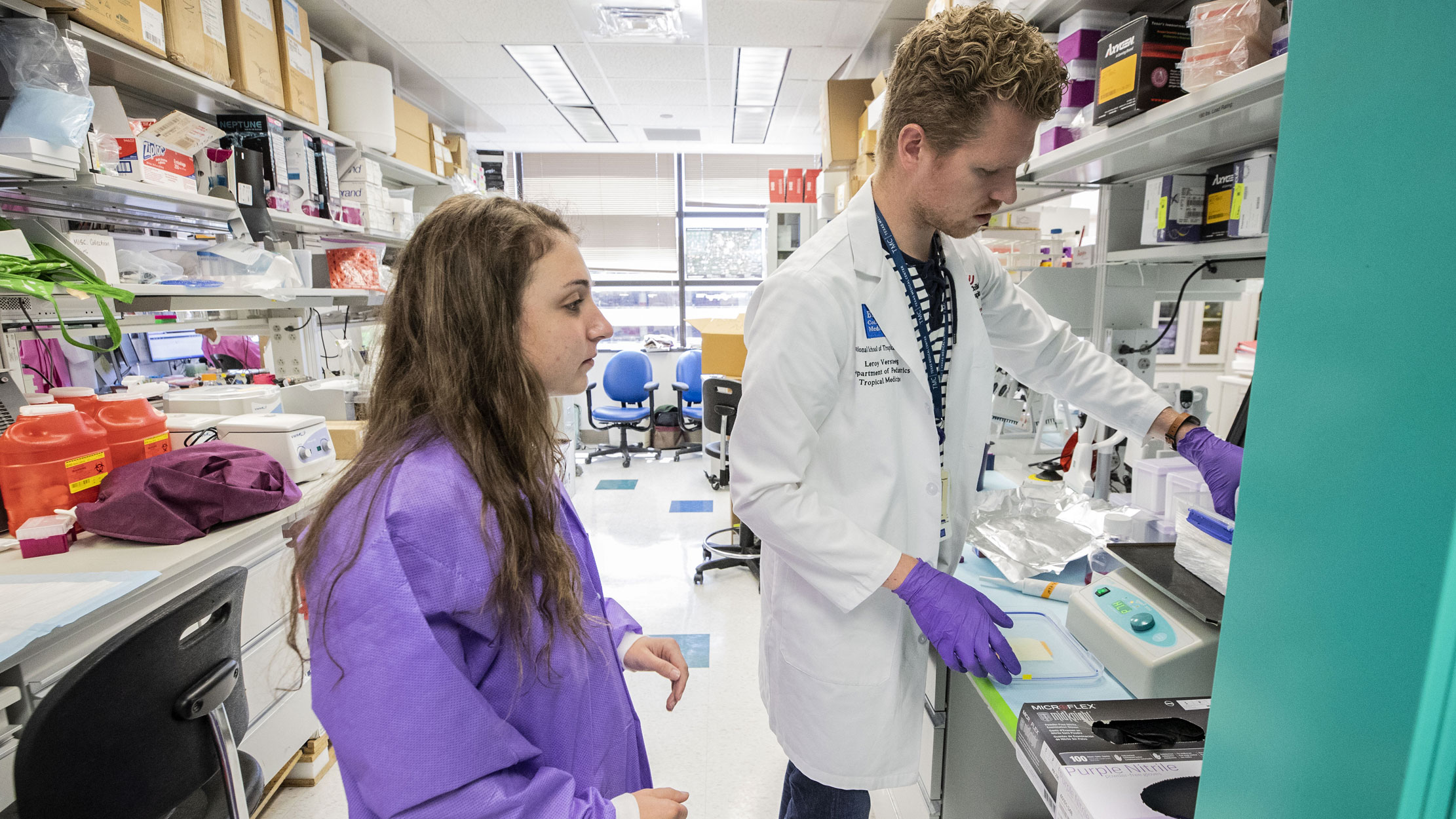

Inside a lab at the NSTM’s Center for Vaccine Development, Katie Lakey, a junior public health major and Summer 2019 Institute student, searches for parasites hidden in blood smears as she gazes through the lens of a microscope.

Outside, the Texas Medical Center is bustling with activity in a way only the world’s largest medical complex can, but Lakey’s focus is complete as she searches for organisms invisible to the naked eye. The hunt for parasites is an intensive process than can take 30 minutes to an hour for a student new to the parasitology field. Sometimes, Leakey shows a teacher what she thinks to be a parasite, only to learn her discovery is merely debris. Other times, Lakey is informed that it is indeed a parasite. The process helps her and other students hone their medical eye to determine the difference between what matters and what doesn’t.

“It’s exciting to be able to make the blood smears and train yourself to find the parasites,” Lakey says. “Usually that’s something you find in PhD programs. To be able to do it now is special, and we have the time to practice it until we perfected it.”

“These doctors understand that, if you want to change the world, you need more scientists, more doctors who say, ‘I want to invest my time into this.”

What Lakey and her fellow Institute students experience is a hallmark of the program: Lab experience that is real and lectures from the BCM professors and practicing medical doctors whose expertise is world renowned.

“One of the beautiful things about the program is that they don’t hold back their top scientists,” Sanker says.

The curriculum is rigorous — 10 days, lasting seven hours each, comprised of multiple labs and lectures in such subjects as parasitology, epidemiology, infrastructure disparities, infectious diseases, disaster relief, health communication, and more.

Farnaz Karimighovanloo, a junior biology major from Tehran, Iran, calls it a good challenge.

“The level of the courses is very high,” Karimighovanloo says. “With that, we were able to take the time to ask them questions about the presentations, and even email them afterwards. That led to me being able to go back and shadow them later in the summer in the area of infectious diseases, which is an area of interest for me.”

The experiences work in concert to paint a picture of the wide array of opportunities available to students in the field of tropical medicine. The career pathways in tropical diseases are far from monolithic. Students learn from doctors in vaccine development, veterinary medicine, infectious diseases, parasitology, public health, mosquitoes, vector-borne diseases, and more. This imparts in students a broader picture of the ways they can utilize their calling to serve.

Students’ eyes are opened to the options before them in tropical medicine, and NSTM faculty hope to spark an interest or reveal a pathway the students have not previously considered. NSTM faculty know they are playing a long game; diseases that impact more than a billion people — along with so many of the factors that contribute to them — aren’t quickly solved. Such great need demands a younger generation prepared to receive the baton.

“These doctors understand that, if you want to change the world, you need more scientists, more doctors who say, ‘I want to invest my time into this,’” Sanker says. “This isn’t an area where professionals can make the money they can in other area. These individuals take on a challenge knowing that no pharmaceutical company or huge commercial enterprise is going to result as a consequence. It’s not lucrative, but the work is significant. Dr. Hotez wants to cultivate that, and he understands that reaching undergraduate students is effective, especially undergraduates who show the depth of interest that Baylor students show.”

SERVICE + EXPERTISE

Baylor University is not the only university using resources to address tropical disease, but it stands out because of the way it melds the service component with expertise in medical training.

It is an investment that draws students, professors and researchers, including Dr. Kelli Barr, associate professor in Baylor’s biology department. Barr, a virologist, tropical disease biologist, Rising Star researcher and member of Baylor’s Tropical Disease Biology group, joined Baylor’s faculty last year.

“What I’ve seen is a university investing a great deal in this area, and specifically in students,” Barr says. “We’re bringing in new faculty, and we’re partnering with Baylor College of Medicine, but we’re also investing in research, missions and the undergraduate electives we teach. The electives here are above and beyond any other university I’ve been to. The expense and preparation put into these courses elevates courses like our clinical microbiology course for undergraduates above the same material students learn in veterinary school in other universities. And the students here are different. They want to help people.”

Barr works alongside Tamar Carter, assistant professor of tropical disease biology; Jason Pitts, assistant professor of biology; and Cheolho Sim, associate professor of biology in Baylor’s tropical disease biology group. Each uses his or her discipline in concert with that of colleagues in research and scholarship that advances knowledge in the field. As they collaborate with one another, they also grow a strong working relationship with NSTM faculty, many of whom travel to Waco regularly to visit with students and faculty. Both sides have found the partnership with NSTM holistically benefits their work, as well as the students they teach.

Sim has collaborated with NSTM faculty to research a transmission blocking vaccine for Brugia, a parasite that causes tropical disease like lymphatic filariases.

“In our department’s experience, today’s students arrive at Baylor with the drive to identify careers of service and positively impact the world,” Sim says. “Baylor’s Department of Biology, as well as the National School of Tropical Medicine, enjoy rich histories of accomplishment in global health. Therefore, collaboratively, we’re uniquely poised to address this need. Further plans for collaboration, in addition to the summer institute program, will advance Baylor’s ambition to become an R1/Tier 1 institution and also uphold its Christian value of service to the weak and afflicted.”

Such plans include a joint Bachelor of Science/Master of Science degree at Baylor and NSTM in biology of global health, expansion of the Institute to grow fourfold to 100 students, and an increased partnership between Baylor University and the Baylor College of Medicine that would elevate the breadth of work taking place at both institutions.

“I can’t tell you how many trips I’ve made to Waco and come back excited,” Hotez says. “What I would like to see is how the National School of Tropical Medicine becomes better integrated into a joint partnership with Baylor University and the Texas Children’s Hospital. There are great advantages to partnering with Baylor. We’re an academic health center, very much the biomedical model. We don’t have economists here, political scientists or humanities scholars. It provides a partnership to enrich this whole approach to poverty-related diseases from a holistic point of view.”

As exciting as future plans are to Sanker and other faculty members at Baylor and NSTM, the present reality of the partnerships continues to bring rewards in the form of change within students.

Lakey aspires to be a medical doctor with a focus in public health, and she plans to participate in medical missions trips at Baylor. Karimighovanloo hopes to return to her native country to address Iran’s HIV problem. She was captivated by the Institute’s health communications class, which spurred her goal to use strategic health communication in addition to medical treatment to address the issue.

Adjetey entered the Institute last summer already with a strategic plan in place — to major in business at Baylor before going to medical school, so he could better understand the business side of bringing treatment to the world. An Institute “Surgery in Developing Countries” class imbued in him a more specific goal to help places like Ghana, where his parents were born.

“You don’t treat the world’s bottom billion to make money.”

“I really learned how, in the U.S., if you have a minor disease, it can be cared for quickly,” Adjetey says. “In other countries, though, when you don’t get care quickly, that disease can morph into a much greater problem. I want to specifically work in a lower-middle- income country to help bridge the gap in health disparities between wealthy and lower income countries. That could look like working through a clinic or partnering with an academic institution and training the people in that country so we can together establish basic infrastructure that provides care for those that need it.”

Each student entered the Institute with a dream and exited with a more specific goal to pursue, shaped by faculty in Houston and Waco who model the mission they hope to continue.

“As Dr. Hotez told us, ’You don’t treat the world’s bottom billion to make money,’” Lakey says. “The goal is to get vaccines and treatment to them for free. I really admired that desire to change the world, and it made us all want to do that, as well — to make the largest difference for the largest amount of people around the globe.”