Fairy Tale Career

From Shakespearean set design and graduate school at Yale, to making Shrek and developing castles for Disney, Doug Rogers, BFA '82, has proven the sky is his limit.

Doug Rogers’ résumé sounds like make believe: art director for DreamWorks’ Shrek; production designer for Disney’s Tangled; associate designer, Into the Woods Broadway musical; artist, The Princess and the Frog; Bee Movie; Flushed Away; Sharktale; Puss and Boots; Luciano Pavarotti’s world tour; HBO’s Deadwood Mysteries; resident designer for the Shakespeare Festival of Los Angeles. All of that is a sampling.

“To me, design is design,” Rogers says. “I helped design the mass transit system in Monterey, Mexico. I also designed chicken salad spread containers in Dallas and magazines for the Woman’s Missionary Union. I’ve designed movies and Broadway shows. I’m the same guy.”

Rogers, who currently is concept designer for Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI), is working on the enlargement of the Hong Kong Disneyland Resort Castle. In 2016, he completed several WDI projects for the new Shanghai Disneyland.

“People always try to tell me, ‘Oh, you’re an animator, or architect or you’re this or that.’ I say, ‘No. I’m a designer,” Rogers says. “I know how to paint and illustrate, but those are necessary tools to do good design work. Some people get it, and some people don’t.”

Rogers was raised Baptist in Paris, Tennessee, home of the world’s biggest fish fry. While in high school, Rogers attended an event in Nashville, Tennessee. There, he met the speaker, Rev. Bill Glass, BA ’57, who, along with Paul Baker’s legacy and Baylor’s strong speech department, influenced Rogers to choose Baylor over Northwestern University and Vanderbilt University.

Rogers grew to love Baylor because the University helped him find a way to pay for his education when he first arrived on campus without enough money to pay for school.

“Baylor took care of me in that moment,” he says. “I had opportunities to leave the University to go to other ones; and, because of their commitment to me, I stayed.”

Rogers worked for the late Ruben Santos, ’59, former longtime director of the Bill Daniel Student Center (BDSC), doing graphic design and displays, running a film series, and designing sets for After Dark and Sing. He recalls comedian Jeff Dunham, BA ’86, emceeing shows for the BDSC and flying his remote-control helicopter towing a banner, dropping BDSC event flyers down 5th Street.

At the BDSC, Rogers also met many famous campus visitors like Van Cliburn, Chuck Mangione, Tom Jones, Neil Sedaka and Amy Grant. Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul and Mary offered Rogers a job in his animation studio in Maine; Rogers declined to finish his degree. He spent days over Thanksgiving break building large Christmas trees that Barbara Santos designed, including trees with Cotton Bowl and Peach Bowl themes.

“We had a crew that became family, and to this day I’m still part of the Santos family,” Rogers says. “Working in the SUB [BDSC] was an incredible experience, and Ruben Santos became an alternative father to me. If it wasn’t for Ruben and his wife Barbara, I probably would have starved. I didn’t have a car, I couldn’t even buy clothes—I was that broke.”

Rogers was also befriended by Sir Heinz Koeppler, a leading British politician and former visiting distinguished professor at Baylor.

“Once, I visited Sir Heinz in his office, and there sat the president of the World Bank and the custodian of Burleson Hall, then myself joining their conversation,” Rogers says. “Sir Heinz had that ability to bring people together and find connections no matter their background. What a gift. This is a man who’d made history helping to start SALT [Strategic Arms Limitation Talks] with the Soviet Union, and I could go see him every week.”

After graduation, Rogers worked in Birmingham, Alabama, and then in Dallas, while also acting on the side. There he met Tony Award-winning set designer Eugene Lee, whose experience includes Saturday Night Live, Sweeney Todd and Wicked. Lee did a production of The Tempest at the Dallas Theater Center, which Rogers called one of the pivotal moments of his life.

“That was the fulcrum; that was it,” Rogers says. “I saw that show night after night after night, primarily to experience the sets. They were unbelievable. The shows he did at the Dallas Theater Center have become some of the most important set design in the history of American theater. I just happened to be there, dumb luck, at the right time.”

After successfully filling in for an ill set designer, Rogers quit his graphic design job and resolved to pursue set design full time. He became a visiting professor at the University of Southern Mississippi while developing his portfolio to apply to the exclusive Yale University School of Drama Master of Fine Arts in theater program. Out of hundreds of applicants from around the world, Rogers and eight other designers were accepted into the design program. In another twist, actor Paul Giamatti was one of the individuals selected for the acting program and later provided his voice for Turbo, a film by Susan Slagle—Rogers then-future wife.

“It was incredibly hard, and I met many brilliant people,” Rogers says. “Classes at Yale, particularly at the drama school, only end when the discussion is over. It was not unusual for us to have classes go eight or 10 hours. You had to defend everything you believed and still do so in a diplomatic way during these intense discussions.”

During a summer break from Yale, Rogers began working at the Los Angeles Shakespeare Festival. He arrived in Los Angeles the week of the Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman murders. The Shakespeare Festival took place blocks from the murder scene.

“Going back and forth from coast to coast, I would be exhausted and cold at Yale and hours later be having dinner with Martin Short and Rita Wilson at events related to the Shakespeare Festival,” Rogers says.

Wilson and husband Tom Hanks were the primary fundraisers for the festival. That summer, Rogers designed the outdoor theater where Hanks played the role of Falstaff in Henry IV.

Roger’s Yale thesis was an innovative set design for Othello, which was well received when he adapted it for the festival. Soon thereafter, a friend recommended him to John Schaffner and Joe Stewart, who hired Rogers to be part of a television show.

“My very first job out of Yale was working under the table—because I wasn’t in the union—on the Friends TV show,” Rogers says. “It was the No. 1 show in America, and I’d never seen it. I’m walking around the set, meeting the cast and going to script readings, trying to fake my way through because I don’t know a dang thing about this show or who is on it.”

Rogers concurrently worked on The Drew Carey Show and designed props for the Rockettes Christmas performance. Next, he sought to work on the Dreamworks film Amistad, but instead producer and film studio executive Jeffrey Katzenberg hired Rogers to work for DreamWorks Animation, which turned out to be another chance of a lifetime.

“They showed me a 10-second clip of a demonstration that they were doing for Shrek, and the images were far more advanced images than Toy Story had been,” Rogers says. “I realized I was looking at the cutting edge of a new industry. All I could think of was Walt Disney going to the movie theater and seeing Al Jolson, and that changed everything for him when sound was invented. I thought, ‘This is the rarest of opportunities that has opened up to you.’”

DreamWorks needed someone not from a two-dimensional animation background who understood three-dimensional space. They heard about Rogers’ Othello set and valued his liberal arts background. During four years of work, Rogers designed roughly 80 percent of the Shrek film and worked with heralded production designer James Hegedus.

“We didn’t know whether it was good or not because we’d been looking at the same thing for years and hadn’t seen the movie with a live audience,” Rogers says.

That changed when a French film critic at a press event, came up to Rogers, kissed him on the cheek and said, “You have made the perfect film.”

Rogers was keen to sprinkle his love of Baylor into the movie.

“When you were coming into Duloc and there’s a sign off to the side that says, ‘Waiting time 45 minutes.’ There’s another line under there, a code that translates into ‘I hate the University of Texas.’ Then there’s a scene when Shrek is in Duloc fighting those knights and they all have emblems on their chest,” Rogers says. “Originally, I had the mascots from the Southwest Conference, but I got found out, so they made me change them. There is a knight with a green and gold knight outfit. That was the Baylor guy.”

Rogers says he once saw an ad from Texas A&M University promoting that some of their computer engineering alumni had worked on the film. It showed a picture of Shrek and Donkey with the words, “He was almost maroon.”

“I saw the ad and I thought about writing Texas A&M and saying ‘No, he’s green because a Baylor guy designed him,’” Rogers says.

Before Shrek was released, DreamWorks was nearing the edge of bankruptcy, and the company asked Rogers to show billionaire Steve Allen a preview of the work that had been done of Shrek when higher company executives happened to be out of town. DreamWorks was planning to ask Allen for more investment. It worked.

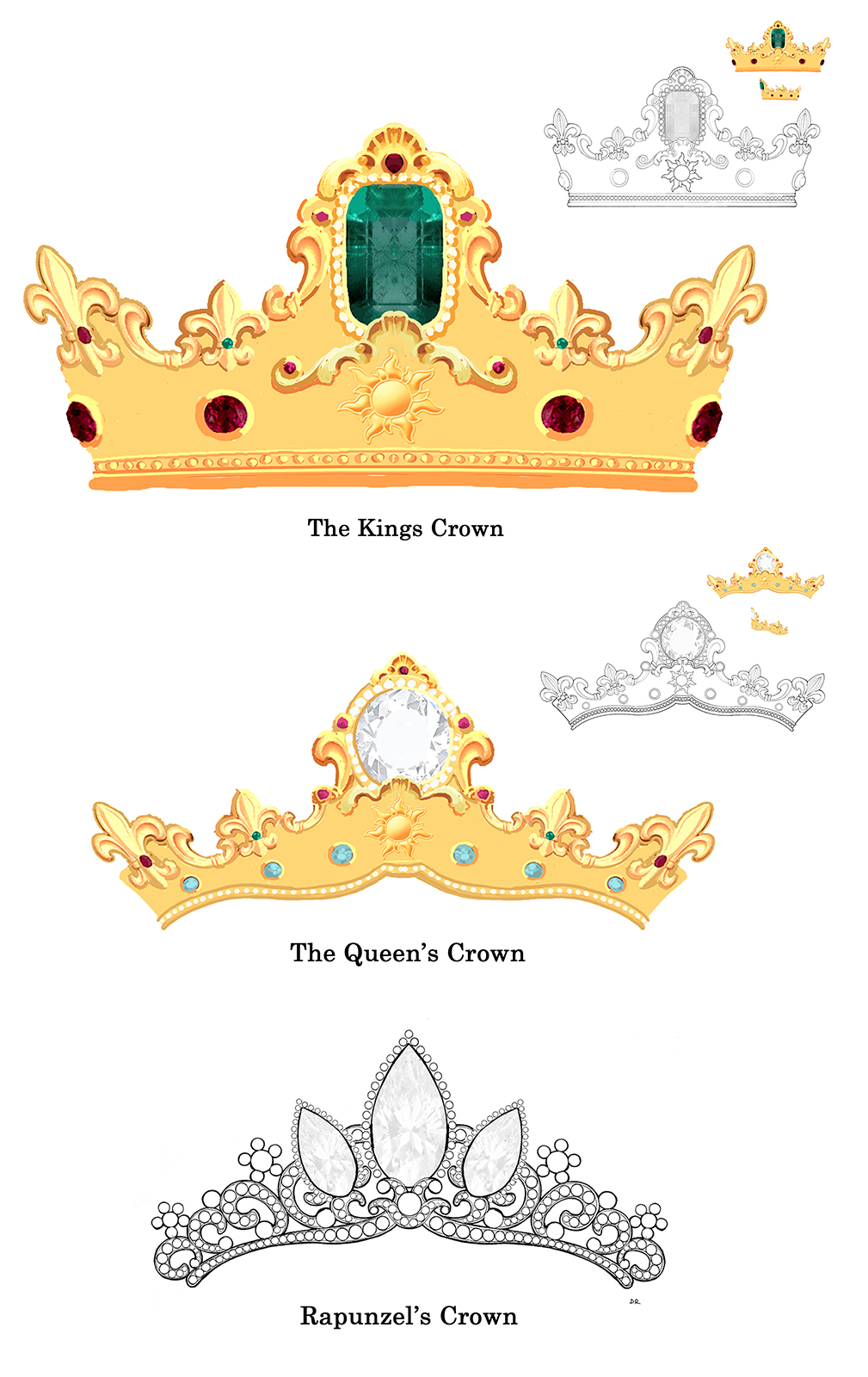

A couple of years later, Rogers was hired by Disney, and he began work on The Princess and the Frog and Tangled. He was about to begin work on Frozen when he was invited by WDI to be part of a creative charrette, a think tank, about the centerpiece of a new park in Shanghai, the Disney castle.

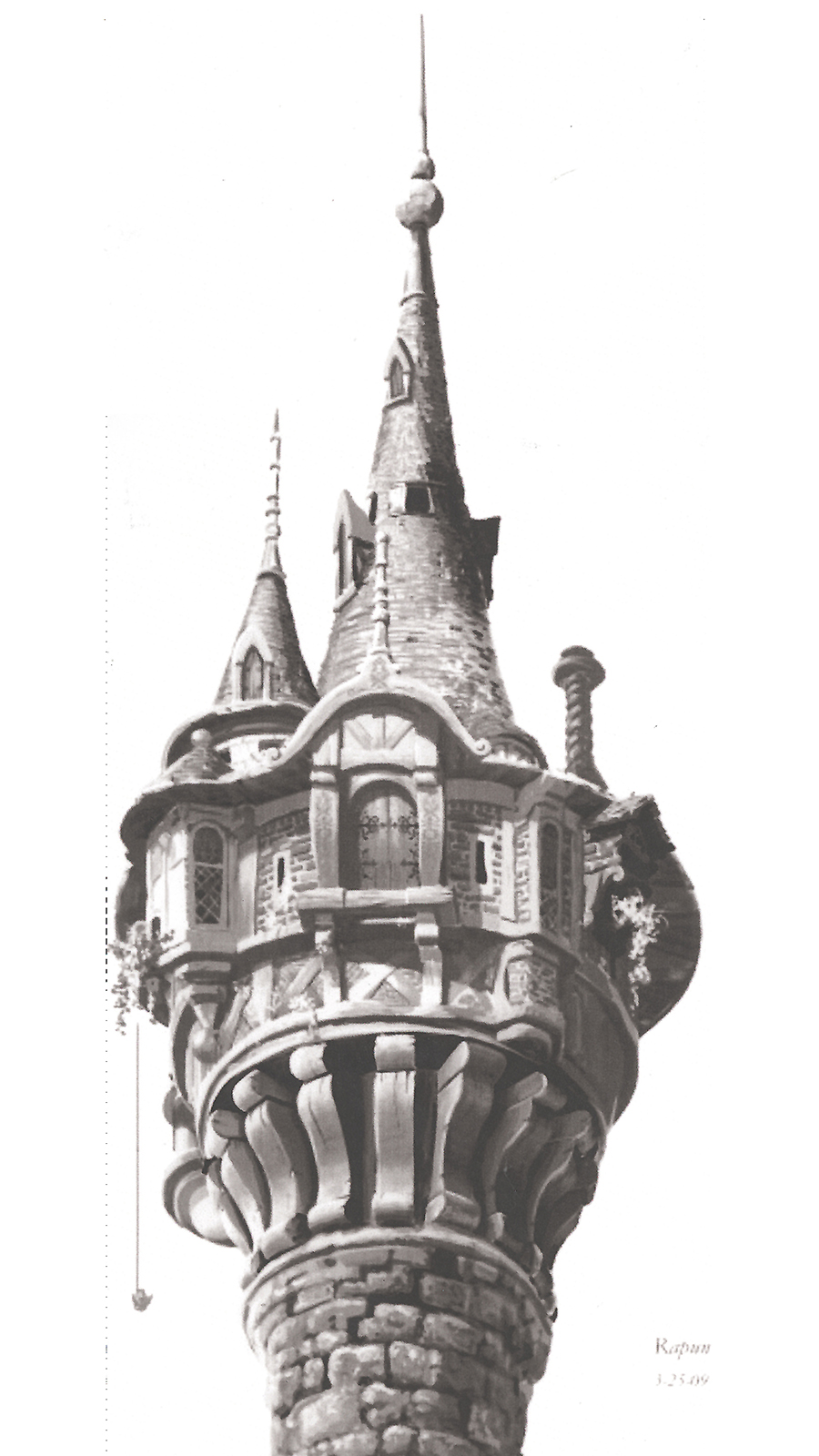

“They liked my castle that I had designed for Tangled, and I thought it was kind of funny that my theater side and my animation side was now coming together for this,” says Rogers, who joined Walt Disney Imagineering in 2010.

Shanghai Disney Resort opened in 2016. The facility’s castle, developed by Rogers, is 197 feet tall with five stories and a basement. It is the largest Disney castle and the world’s largest true castle designed since Germany’s Neuschwanstein Castle was built in the 1870s.

“There’s a lot to do and see in the castle; it’s like its own land. I wound up working on or designing 17 other things for the park in Shanghai,” Rogers says.

One particular project united Rogers with a fellow Disney Imagineer and fellow Baylor graduate Stephen Cargile, BFA ’87, who started a long Disney career while he was a Baylor student. Cargile sent to The Disney Studios a depiction of Sleeping Beauty for a movie poster, and they hired him, beginning his long career with the company, with a primary focus on designing characters.

In Shanghai, Rogers and Cargile were part of a three-person team that designed a 60-foot glockenspiel-style clock tower. Rogers developed the structure, and Cargile designed the clock’s animated characters. A video of them describing the 2016 project can be found on YouTube.

“Steve designed and incorporated characters from Star Wars, Marvel, Pixar and Disney animation characters. This was the first time that characters from across the Walt Disney Company were united together in one creation,” Rogers says.

Since then, Rogers has worked on projects for other Disney parks and hotels in Anaheim, California, and Paris. He still does theatrical set design and speaks around the country as time allows. Rogers returns to campus on occasion to visit with theater and film and digital media students.

He says taking people on an adventure and bringing them safely back home is at the heart

of Disney.

“There’s a trust, a certain quality people expect with Disney. The fairy tales, especially, contain basic underlying human morality stories. We really do care about that,” Rogers says. “We also layer the richness of the stories so that there’s always something that you didn’t see before, or you get a joke later on in life that you didn’t understand as a kid. We never forget that everybody was a child, and there’s still a portion of that child in everyone. That child is willing to take a risk and an adventure and is eager to learn something or experience something new.”

Rogers, who has enjoyed a long, illustrious and varied career, says that his fairy tale work experience is far from over.

“I have always had the belief that I need to be doing what I call national- or international-level work,” he says. “It may reach into your hometown community, but I always wanted to be doing something that was on that level of influence. I felt like I had something to say, and I wanted to say it. I still believe I have something to say, so I still am out there plying my trade. I’m not tired of it yet.”

Reflecting on his career thus far, Rogers is effusive in crediting his Baylor experience and the education for its role in his successes.

“My Baylor education was the greatest gift I ever received because it’s as good of a liberal arts education as you’re going to get. Baylor exposed me to so many different ideas and experiences,” he says. “A great liberal arts education inspires a way of thinking—thinking outside the box when most people don’t even see the box. As a designer, we see the world and how it’s composed and seek how we can improve it, or how we can fit into that world. I always examine everything, which definitely ties back to that liberal arts experience. I always look at things from different angles, not from just one.”

Given the near certainty that Rogers will keep creating magical experiences for millions, the rest of the world should be thrilled that Rogers’ happily ever after hasn’t happened yet.