Baylor and the Final Frontier

Ursa Major, Ursa Minor and other Bears up there

“For the eyes of the world now look into space — to the moon and to the planets beyond — and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest but by a banner of freedom and peace. We have vowed that we shall not see space filled with weapons of mass destruction but with instruments

of knowledge and understanding.” —President John F. Kennedy, Sept. 12, 1962

In his 1962 Address at Rice University on the nation’s space effort, President John F. Kennedy challenged American scientists to put a man on the moon in less than a decade. The nation’s eyes turned heavenward at the dawn of an era that would bring about more technological advancement than experienced in the totality of humankind to that point.

Texas, especially the Greater Houston area, was at the epicenter of what became known as the “space race” between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The space industry’s influence on Southeast Texas and the Lone Star State as a whole was evident.

Baylor University was not detached from this as many 1960s graduates began their careers in Southeast Houston, at least in some small part due to the area’s growth alongside NASA. More than a half century after President Kennedy’s challenge, the vast expanse of outer space remains a relevant realm for many Baylor alumni, faculty and current students.

Perseverance

James Hartsfield, B.A. ’85, is manager of communications and public affairs at Houston’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Those who remember the 2003 space shuttle Columbia tragedy may also recognize Hartsfield’s voice from the NASA-TV broadcast of the shuttle’s fateful re-entry. He also moderated media availability with flight director LeRoy Cain a few days after the accident. It was a somber day for all those involved with the Columbia mission, including Hartsfield, who was the public affairs officer for the space shuttle program at that time.

“The reason people love working for NASA is because we don’t quit. We persevere,” Hartsfield says. “It’s not because we don’t fail. We have failed tragically; but, when we fail, we don’t quit. It’s that ability to continue and keep trying. We remember the Columbia for more than the accident itself. We remember because we learn from it. The ability to recover from it is something I carry with me.”

He has never been to outer space in his more than 30 years as a NASA employee, but he certainly understands the endurance dynamic of space exploration. He also personally knows about perseverance.

Hartsfield, a Waxahachie, Texas, native, values his Baylor education, saying the University provided him with the proper tools for his career. He raves about the journalism department and the sundry talented writers and media members it has produced. But Baylor holds a special place in his heart for one singular reason: second chances.

“I was a really terrible person and student when I got to Baylor,” Hartsfield says, acknowledging that he was expelled after three semesters with a 0.8 cumulative grade point average. “I was on a self-made downhill trajectory.”

Essentially disowned by his parents, Hartsfield remained in Waco and worked as a motel night clerk, a pawnshop employee and a gas station attendant. Eventually, his friends who were still at Baylor convinced him that he was wasting his potential and his life.

Nine months after being expelled, Hartsfield arranged a meeting with Abner Anglin “A.A.” Hyden, Ed.D., who at the time was Baylor’s vice president of student life and dean of student affairs.

“I wish I could remember everything that was said, but I basically had to convince him to let me back in school — something I don’t think any university would have done with my track record,” Hartsfield says. “I never really stayed in touch with Dr. Hyden, but I have never forgotten what he did for me.”

Hartsfield hitchhiked to Waxahachie for what he describes as a “long weekend of convincing” his parents that this time would be different.

“Baylor and my parents forgave my dismal college start and allowed me another chance that I totally did not deserve,” Hartsfield says. “Those Christian values of forgiveness and belief that people can change are uniquely Baylor to me, and I am forever grateful.”

Shortly after returning to Baylor, Hartsfield found the biggest difference maker: a definite career path in journalism. He eventually was hired as managing editor for a small Galveston, Texas, area newspaper and covered the January 1986 space shuttle Challenger accident for that paper. He also covered President Ronald Reagan’s visit to Johnson Space Center three days after the accident.

Those events piqued Hartsfield’s interest in potentially working for NASA. He contacted someone in the Space Center communications office about doing a personal profile for the newspaper. To his astonishment, Hartsfield arranged an interview with longtime NASA spokesmen and public affairs officers John E. “Jack” Riley and Doug Ward, known as the “Voices of Apollo 11” mission that landed the first person on the moon. However, Hartsfield’s actual agenda was to get his foot in the door.

“I said, ‘I’m looking for a job, and here are all my clips and all my photos and everything I’ve done,’” Hartsfield says. “They were great people.”

NASA had no position for him at the time, but several months later Riley contacted Hartsfield for a position in the public affairs department. He started about a year before the September 1988 launch of Discovery in the space shuttle’s return to flight. His first tasks included increasing communications among employees through NASA’s in-house newspaper.

During the first half of his career, Hartsfield supported more than 80 space shuttle missions, including nearly 20 launches and landings, in mission control as a voice of NASA.

“Working on those missions and events in that room with that brilliant team was an amazing privilege and experience,” he says.

Hartsfield currently leads NASA’s award-winning communications team. “The team here today is the best I have ever worked with,” he says. “Even after 33 years, no two days are alike. Every day is new.”

Hartsfield was not the first Baylor alumnus to work at NASA and he certainly is not the lone Bear currently at Johnson Space Center. Brandi Dean, B.A. ’03, who also began her career as a newspaper journalist, is deputy manager for communications and public affairs. A Jasper, Texas, native, Dean never imagined being a part of the space industry as a child but has worked at NASA since 2006.

“NASA and space were not on my mind at all,” Dean says. “I was always reading and writing. But this has turned out to be a wonderful job for me.”

Several other Baylor alumni work directly at or tangentially with Johnson Space Center (JSC), including Dylan Mathis, B.A. ’94, M.A. ’96, who is integration manager for operational programs in the JSC external relations office.

“We work with astronauts to tell their story and communicate to the world all they do to benefit us on Earth through scientific research and exploration,” Mathis says. “Getting to work with storytellers for the commercial crew program and for the International Space Station — honestly, it’s the second-coolest job in the world.”

Additionally, current Baylor communications major Megan Hale recently completed a NASA internship. Hale, a Houston native, regularly visited JSC and attended space camps as a child. Unlike Dean, she dreamed of working in the space industry but did not envision her first encounter with NASA as an adult to be through communications.

“I came to Baylor as a biology major; looking back, I’m not a biology person at all,” Hale says. “I’ve always loved science because the more you learn about science, the clearer the Lord becomes through his creation.”

Hale shifted her academic major and says a 16-week NASA internship, which she completed last spring, provided an ideal convergence of her passion (science) and skill (communications). NASA asked Hale to continue on a part-time basis, but she was ready to return to being a student. Nonetheless, she hopes to return to NASA after graduating in December 2022.

“It’s a big commitment, and it was difficult at times,” she says. “But it was a childhood dream come true to intern at NASA.”

Protection

Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Purdy Jr., B.S. ’93, M.S. ’95, was destined for a career involving three things: computers, military and space exploration. A self-described “nerdy introvert” as a child, Purdy was mesmerized by the avant garde video game systems of the early 1980s. He was also the grandson of a U.S. Army lieutenant colonel and the son of a U.S. Air Force colonel who was a longtime space acquisitions officer.

Purdy’s father encouraged his son to attend a college with an Air Force ROTC scholarship and to pursue a career in computers, which was burgeoning at the time.

“One day, my parents tossed a bunch of college admissions books on the desk and said, ‘Pick one,’” Purdy says. “Baylor was on top, and I thought, ‘What’s Baylor?’”

Purdy was born in Ohio but grew up in Maryland, Alabama, California and Texas, where his family were residents as he began narrowing his college choices. He visited Rice University, the University of Texas at Austin and Baylor, where he immediately felt at home.

“It was literally every sort of visionary element as we wandered around campus,” Purdy says. “We visited during a break, so we got to talk to the deans, who walked us around, unlike at other places.”

Purdy attended Baylor as an engineering major with an emphasis on computers. He was a member of Air Force ROTC Detachment 810, which began at Baylor in 1948 —10 months after the national organization’s creation. He also was president of the Arnold Air Society, an Apple student representative and worked in the computer store. Purdy was an Air Force ROTC distinguished graduate and remained at Baylor for graduate school. Along the way, Purdy realized his specific professional skills.

“I was never one of the engineers that wanted to continually do breadboard engineering; that was never me,” he says. “The deepest, darkest depths of thermodynamics were not my cup of tea. Project management and managing teams suited me better.”

That is reflected in Purdy’s military career, which began in 1995 at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio where he was a simulation systems engineer. After various assignments and having climbed the ranks to colonel, Purdy was named director of space and missile systems center special programs with the U.S. Space Force in 2019.

Purdy was promoted to brigadier general in August 2020 and accepted his current assignment as 45th Space Launch Delta Commander (previously known as 45th Space Wing) three months later. He leads the safe and secure processing and launching of U.S. government and commercial satellites from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. Purdy is the final approval authority for all launches on the Eastern Range, a 15 million square-mile area that supports an average of 25 launches per year. He also manages delta launch and range infrastructure supporting NASA, commercial and missile test missions.

“I have multiple titles and wear many hats,” Purdy says. “Part of my job is managing the actual mechanics of the base here in Florida, but we also have personnel and equipment on Ascension Island in the South Atlantic. Then, you have the operational side, which involves scheduling launches, managing payloads, training forces and maintaining operation centers — making sure things run smoothly.”

Purdy estimates there were four to six rocket launches per year at Cape Canaveral a decade ago. However, in the last 12 months, there were 250 requests to launch, of which more than 200 were approved, 50 reached countdown status and 39 launched.

“We’re planning in a few years to support launch rates up to a few per day, every day,” he says. “We may be asked to be ready to launch in a couple of hours. That’s a whole different mindset.”

As the world — and the United States in particular — becomes more reliant on technology-based communications, protecting and preserving space is vital, and the Space Force is tasked with that assignment. Organized under the Department of the Air Force in a manner similar to how the Marine Corps is organized under the Department of the Navy, the Space Force was founded as an independent military service in December 2019. However, its roots trace back nearly four decades to the creation of the Air Force Space Command in September 1982.

“Back in the day, there were a lot of serious issues for the Air Force to focus their minds on. Even on a good day, space wasn’t necessarily the top one,” Purdy says. “Now that we split out a space force, we have dedicated full-time leadership that has direct access to Secretary of Defense offices.”

While at Baylor, Purdy was exposed to tools and concepts that laid the groundwork for his career. He also learned the value of teamwork, something he admits does not come naturally for most engineers.

“A lot of engineers are famously introverted. Forcing us on teams to coordinate with each other is incredibly important because that’s real life,” Purdy says. “People work together to achieve some goal for a company or government. The activities I participated in at Baylor, especially the cross-disciplinary ones, hit the most paydirt. My ROTC experience was really valuable because it gave me a lot of Air Force-specific ideas, but not all the ROTC folks were engineers, and we came at topics from many different angles. We want a diversity of thought, backgrounds and experiences to provide a better answer.”

Preparation

While Purdy leads a segment of the Space Force that largely focuses on protecting America from outside threats, two Baylor alumni focus on preparing future military leaders and policy thinkers.

Space Force Maj. Jamil Brown, B.A. ’09, is an Institute for Future Conflict Fellow and political science professor at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, teaching international relations, space policy and national security classes. He is a space operations officer and former Air Force Weapons School instructor. Brown’s previous assignments include GPS satellite operations, missile warning satellite operations and planning space operations support for U.S. Forces in Korea.

Brown sees a need to educate Air Force Academy students as well as the general public on the necessity of the Space Force. His space policy class aims to explain the importance of space while accepting that the answer may not be readily available.

“A part of our responsibility at this place in time is to define what space is supposed to look like, which then plays into some of the other things I do,” Brown says. “I spend a lot of time out in the community talking about space. Throughout all of those conversations, I’m reminding folks that space warfare isn’t blatantly two objects hitting each other.”

The son of Air Force parents, Brown was born in Florida but also lived in Alaska and Germany before attending high school in Texas. He enrolled at Baylor as a pre-med chemistry major but changed course after taking an economics class on a whim during his second semester. He also lived in Baylor’s Leadership Living Learning Center as a freshman.

“What initially drove me to attend Baylor was the idea of getting to work with different people from different backgrounds in a servant leadership capacity,” he says. “There was a very personal connection at Baylor. I can still name every single professor I had a Baylor. Through the way they taught their classes, they modeled what leadership should look like, especially in the military.”

The leadership characteristics Brown witnessed in his Baylor professors shaped who he is as an Air Force Academy professor and a Space Force major. He makes a point to know everyone’s name and to be empathetic to each person’s struggles.

“One of the things I highlight to all my students on the first day of class is that being overwhelmed is normal, but communicate that you’re overwhelmed and we can have a conversation and figure things out,” Brown says. “That approach 100 percent came from Baylor.”

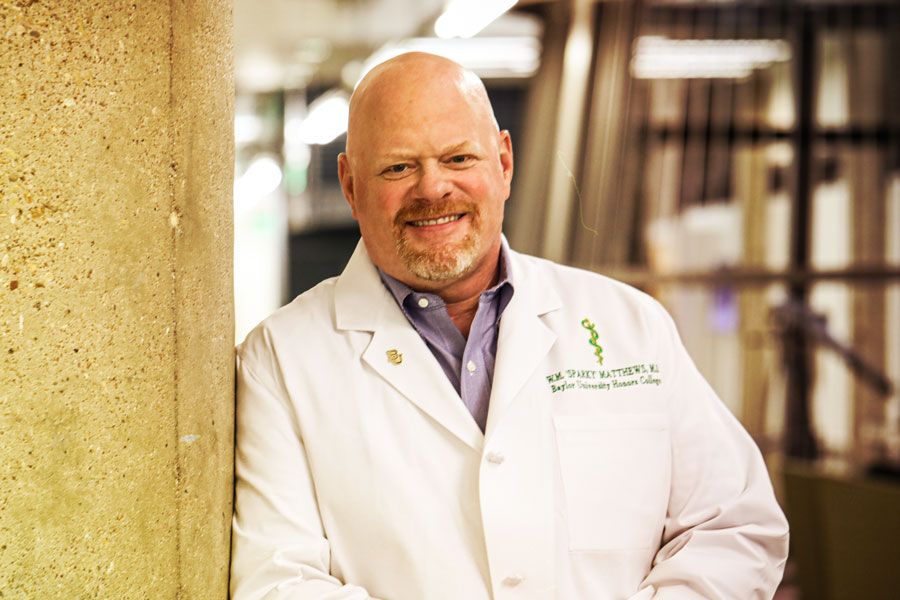

Likewise, Walter M. “Sparky” Matthews, B.A. ’92, M.D., the first Space Force Surgeon General, launched his career from Baylor. When Matthews retired as a colonel after nearly three decades of service in the Air Force and Space Force, he returned to his alma mater.

“I used to tell people my four years at Baylor were the best four years of my life, but that clock has started over again,” he says.

Matthews, an Honors College clinical professor and pre-med advisor, retired from military service and joined the Baylor faculty in February 2020. After meetings with the other service surgeons general and government agency directors about the military’s response at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Matthews has been an important member of Baylor’s COVID-19 Health Management Team.

“It’s like God filled my toolbox and gave me a house to build when I got back here,” he says.

Matthews, an Austin native, says he was “born with burnt orange hair” but spurned his University of Texas at Austin family for Baylor. He admits he is unable to say why he chose Baylor, that it was “purely the hand of God” that brought him to Waco. A couple of his older friends were already at Baylor when he was a high school senior; Matthews visited them at Penland Hall and attended a couple of classes.

“By the time my dad came to pick me up, I didn’t want to go home,” he says. “I never wanted to leave this. Baylor was home for me.”

Matthews was a member of the Golden Wave Band and sang in a group at First Baptist Church Waco, where he met his wife. He was mentored by David Pennington, Ph.D., and Bill Hillis, B.S. ’53, M.D., who encouraged Matthews to join the Air Force.

“There wasn’t a part of my Baylor experience that wasn’t ideal,” Matthews says. “Since before I graduated, I wanted to come back and do what I’m doing now. I wanted to be Bill Hillis to a new generation of students.”

The possibility of future space travel for the average person has broadened somewhat in recent years. Matthews, an aerospace medicine specialist, continues to study the effects of the air and space environment on the human body. In that regard, he likens the progression from air travel to space exploration to mankind’s progression from nautical navigation to deep-sea exploration.

“When man first got out onto the ocean, suddenly the environment was moving in a way that their body wasn’t used to, which causes seasickness — very similar to air sickness,” Matthews says. “Eventually came a long-duration voyage where the food, sun exposure, temperature, wind exposure are all different. We learned this by experiencing it. When we started going to the depths of the ocean, that’s like going from aviation to space. It’s a very similar transition.”

Baylor alumni help shape America’s outer space presence in many ways. Perhaps one day, Bears will board a spaceship for a weekend getaway to one of the stars that create the constellation Ursa Major.