Illuminating a Giant

Baylor professor helps shed light on the legacy of World War II hero and civil rights icon Doris Miller

Nearly eight decades after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the historic echoes of the events of Dec. 7, 1941, still add a sense of gravity to each word spoken on that hallowed ground. Such was the case Jan. 20, 2020 — Martin Luther King Jr. Day when U.S. Navy officers and federal officials gathered with the descendants of a humble Navy messman. He was the son of Waco sharecroppers and a man whose impact remained hidden in plain sight for decades.

Against the backdrop of Pearl Harbor, Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas B. Modly used carefully chosen words to explain how a Naval aircraft carrier would be christened for a sailor who was limited by the racial prejudices of his day to the ship’s lowliest job. Modly explained that the USS Doris Miller would be the first supercarrier named for an African American and the first named for a sailor. Modly chose, in part, the words of Baylor history professor T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D., to amplify Miller’s impact:

“Doris Miller’s heroic actions at Pearl Harbor and his quiet but persuasive voice as an advocate for positive change constituted a vital contribution toward the full and equal acceptance of Black men and women in the U.S. Navy and the nation that it serves.”

The use of Parrish’s words further illuminated that Miller’s impact had been diminished for too long. It was not long ago that Parrish’s understanding of Miller was limited,

as well.

Parrish, The Linden G. Bowers Professor of History at Baylor, spent his formative years in Waco. His father served at Pearl Harbor in 1941, barely 100 yards from Miller’s heroic station. Despite that proximity, Parrish and his father, along with a majority of Americans, heard little about Miller in the decades that followed the war.

In the process of contributing to the efforts to fund and construct a memorial to Miller in Waco, Parrish partnered with his friend and collaborator Thomas Cutrer, Ph.D., professor emeritus of history at Arizona State University, to write what would prove to be the first and only scholarly biography on Miller: Doris Miller, Pearl Harbor and the Birth of the Civil Rights Movement.

What began as a simple life story of a World War II hero rapidly grew in scope. Old newspaper articles, interviews and oral histories pieced together a more complete picture. Their research supported the book’s ambitious title.

Miller’s actions at Pearl Harbor were a catalyst that led to the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces, invigorated the forthcoming civil rights movement, and changed the nation in a way that far exceeds the recognition he received.

An American Hero

Miller was an expert marksman, a good quality for a serviceman in a time of war. However, his superiors on the USS West Virginia, the ship on which he served at Pearl Harbor, likely had no idea.

“Doris Miller grew up in a segregated nation, a segregated society, and he served in a segregated Navy,” Parrish says. “It was easy for the Navy to ignore a man like Doris Miller.”

Family and neighbors were perhaps the only ones who knew from the start how suited for service Miller truly was. His reputation for marksmanship developed as he hunted squirrels in the Speegleville countryside surrounding his Waco home. Miller was a tremendous athlete and played fullback on the A.J. Moore High School football team. He also worked in restaurant kitchens as a young man to support his family.

“The African American press eventually publicized Doris Miller’s heroics early in the war and called him the first American hero of World War II.”

When Miller enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1939, institutionalized discrimination limited his options to that of a cook third class or “messman.” He worked in kitchens, processed laundry and tended to his supervisors’ immediate needs. As a Black man, he was ineligible for promotion per Navy regulations.

“Of all the armed services, the Navy treated Black soldiers worse than any branch of the military,” Parrish says. “African Americans were confined to the worst kinds of jobs on board.”

Two years after enlistment, Miller was collecting laundry below deck in the early morning hours of Dec. 7, 1941. When the surprise attack began, Miller immediately reported to his battle station, only to discover that its anti-aircraft gun had already been destroyed. An officer ordered him to help move Capt. Mervyn Bennion, who was already wounded in the attack, to a safer position. Miller raced to a vulnerable part of the ship and moved the captain amidst heavy fire.

It was then, as the USS West Virginia began to sink, as sailors began jumping overboard, that Miller’s actions took a remarkable turn.

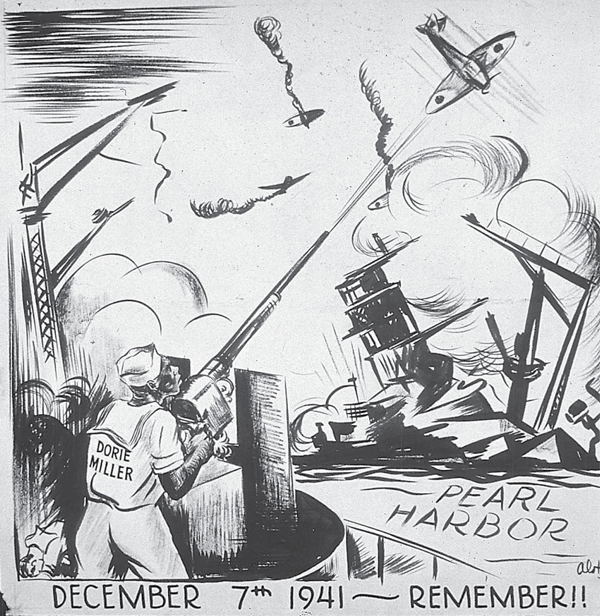

To the surprise of multiple officers, Miller manned one of two unmanned .50-caliber anti-aircraft guns and — despite having no training in the gun’s operation — began to fire. For 15 minutes amidst the chaos around him, Miller fired at Japanese aircraft until exhausting the gun’s ammunition.

Miller turned his attention to the water, which was oil-slicked and already aflame in spots. He pulled men to safety, “unquestionably saving the lives of a number of people who would have been lost,” according to the ship’s executive commander Roscoe Hillenkoetter.

When finally ordered to abandon ship, Miller was one of the last three men to leave the West Virginia. He then swam nearly 400 yards to safety, dodging Japanese fire and the wreckage of the USS Arizona along the way.

Miller’s fellow sailors took notice. Decisiveness and courage transcend rank or background, and word spread that an African American soldier had stepped up in trying conditions. His actions became legendary.

“The African American press eventually publicized Doris Miller’s heroics early in the war and called him the first American hero of World War II. And he was,” Parrish says.

Legends sometimes present historians with different versions of a story to examine for accuracy. While some retellings have Miller shooting down numerous planes, forensic evidence does not support that. What he accomplished, however, was even more meaningful.

Willing to Fight and Die

Miller’s actions at Pearl Harbor were extraordinary, and they reinforced a truth that should have been more ordinarily recognized: Black soldiers were also patriots, capable of stepping up in leadership, serving their fellow soldiers amidst life and death trials, and worthy of the full rights of being sailors, soldiers or citizens. It was a reality that the Navy wasn’t initially eager to recognize.

Word of mouth was the initial springboard for the fact that a Black sailor had led, served and saved at Pearl Harbor. Rumors circulated all the way to Black journalists in the North, who asked the Navy to make his actions public.

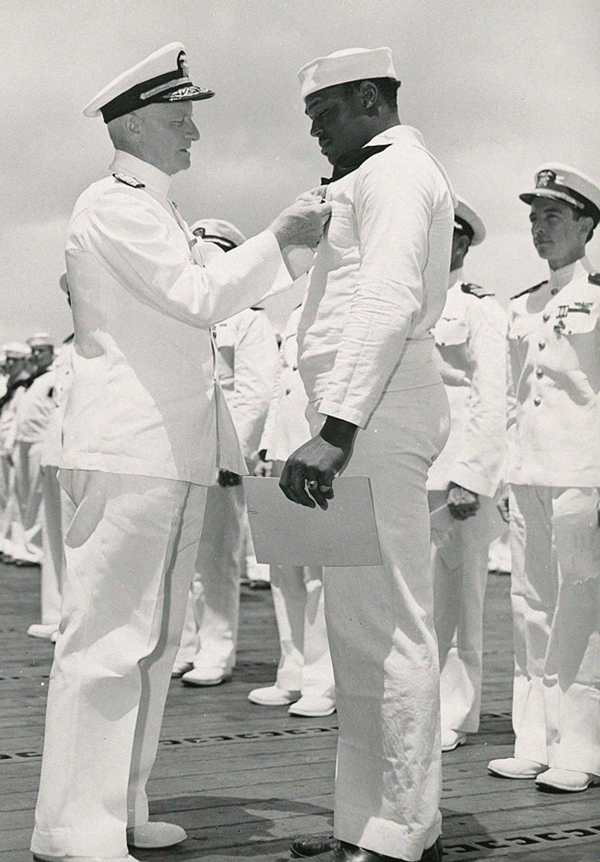

“The Navy was very reluctant to recognize what Doris Miller did, to release his name and to authorize the awarding of any medal, any distinction to him,” Parrish says. “It finally relented, but only under pressure.”

The journalists gained allies, including the NAACP and Northern politicians of both parties, in the push to highlight and honor Miller. Their persistence wore through the Navy’s initial defenses, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt eventually encouraged the Navy secretary to take action.

Miller was finally revealed as the anonymous Pearl Harbor hero, but Congress could not muster the support to award him the Congressional Medal of Honor, settling for the Navy Cross — the third-highest Naval honor at the time. He returned to serve on the homefront, publicizing war bonds and generating support for the U.S. war effort. Those speeches grew Miller’s confidence and berthed a desire for a leadership role in the U.S. war effort and the push for full civil rights for Black Americans.

In important ways, Miller had already done his part. The days after his heroism at Pearl Harbor were key in bring about more opportunities and recognitions for Black Americans in the military.

“Historians talk about the long civil rights movement, stretching all the way back to the colonial era,” Parrish says. “Military actions have long played a role in that. African American men participated in military action with White Americans in the American Revolution and subsequent wars. They did these things with a purpose, like Doris Miller — to show their patriotism and prove not only their fighting ability as worthy of respect, but to show their citizenship and prove their merit as full citizens of the United States, willing to fight and die.”

Parrish says World War II was the war that brought “permanent results,” and Miller was a catalyst. His actions rallied Americans to the cause and launched what was known as the Double V campaign: victory over tyranny abroad and victory over discrimination

at home.

“These moments were integral in pushing forward the civil rights movement to the crescendo that we now recognize and emphasize from the 1960s,” Parrish says.

In 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order desegregating the armed forces. Tragically, Miller was unable to celebrate. His tour of the homefront after Pearl Harbor eventually came to an end, and he was redeployed to the Pacific theater. His ship was sunk by a Japanese torpedo Nov. 24, 1943, at the Battle of Makin. Miller, 22, was not among the survivors.

A Permanent Legacy

Miller’s name continued to be heard long after his death in rallies, churches and other facilities where people gathered.

“Every time that a civil rights leader in the late 1940s talked about the great military service of African Americans throughout history,” they brought Miller’s name forward,” Parrish says, “as a hero, but also as a real catalyst to the ongoing civil rights movement and the success it achieved.”

Miller became a hero to millions of Black Americans, including Eddie Bernice Johnson, who was a young Wacoan at the time. Johnson is now the U.S. Representative for the 30th Congressional District of Texas.

Attendees pose with the statue of Doris Miller at the Doris Miller Memorial dedication in Waco, December 7, 2018.

“To have this man do what he did to save this nation, knowing what he had been through as a Black man, to put your nation above personal treatment,” Johnson says. “He was willing to give his life to save his superiors. I don’t know that there is a higher giving of one’s talent.”

Johnson has carried the mantle begun by past legislators to present Miller with the Medal of Honor, the Navy’s highest award. Those efforts continue, and awareness of Miller’s legacy is gaining momentum.

Efforts to build a Waco memorial to Miller began in earnest more than a decade ago. Parrish provided historical perspective to the project by writing a Miller history for the Request for Proposals for a sculpture, which now graces the memorial along MLK Drive in Waco. Parrish partnered with Cutrer upon discovering the lack of a scholarly biography of Miller.

“We wanted the book release in conjunction with the unveiling of the statue, but I had no idea what it would turn into. It became a much bigger story,” Parrish says.

“His story, his impact and his influence should become even greater and even more permanent for future generations.”

The Doris Miller Memorial was dedicated in 2018. The book, Doris Miller, Pearl Harbor and the Birth of the Civil Rights Movement, provided scholarly heft to efforts to honor him.

Unbeknownst to Parrish, the U.S. Navy was also considering ways they could elevate Miller’s name and legacy. The Navy had honored Miller in 1973 with the christening of the USS Miller, a destroyer escort ship. Modly, however, had his sights on something larger.

The Gerald R. Ford Class — America’s latest aircraft carrier class — are modern, nuclear-powered supercarriers staffed by thousands. No supercarrier had ever before been named for a sailor, but that changed at the USS Doris Miller naming ceremony in 2020 when a messman was elevated alongside U.S. presidents.

Parrish and Cutrer were invited to the naming ceremony in which Modly read a selection from their book. Parrish was unable to attend, but it was a meaningful moment for him and for others who, decades prior, had carried the torch to honor Miller.

The USS Doris Miller is scheduled to be laid down in 2026, launched in 2029 and commissioned in 2032. It will be the fourth supercarrier in the Ford class, following the USS Gerald R. Ford (commissioned in 2017), the USS John F. Kennedy (launched in 2019) and the USS Enterprise (currently under construction).

Closer to home, the Doris Miller Memorial with its dramatic Miller statue against the backdrop of the Brazos River and the forthcoming vessel serve to more fully illuminate the impact of a man who overcame racism, helped a nation more fully live out its founding ideals and made the ultimate sacrifice for his country.

“Doris Miller’s legacy is huge and permanent,” Parrish says, “His story, his impact and his influence should become even greater and even more permanent for future generations.”