Honoring Heroes

McLane Stadium's South Plaza now houses two new statues memorializing the bravery and service of alumni Medal of Honor recipients

The Battle of Iwo Jima had raged for weeks, and the morning of March 8, 1945, dawned with no promise of respite. Some 75,000 U.S. Marines had been charged with capturing the small island from more than 20,000 enemy soldiers established in hundreds of defense fortifications and miles of tunnels. It would become one of the most famous battles in World War II.

1st Lt. Andrew Jackson “Jack” Lummus Jr. died March 8, 1945, from wounds he suffered while fighting in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

That March morning would prove to be the last in the life of 1st Lt. Andrew Jackson “Jack” Lummus, Jr., a Baylor University alumnus (1941) who had grown up halfway around the world in Ennis, Texas. A star athlete at Baylor, he had gone on to play for the New York Giants in the NFL before enlisting in the U.S. Marine Corps a month after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

With officer casualties mounting during the fighting, Lummus had only days earlier been placed in command of a rifle platoon in Company E of the 27th Regiment. He was a trained Marine and, therefore, fully ready to meet the demands of responsibility when he led the platoon on a charge of Japanese positions.

Moving ahead of his forward lines after the platoon encountered heavy fire from concealed concrete pillboxes, Lummus was knocked to the ground by a nearby grenade explosion. He arose uninjured and succeeded in knocking out a pillbox containing three enemy fighters before coming under fire from a supporting pillbox and being hit by a second grenade, which sent shrapnel into his shoulder.

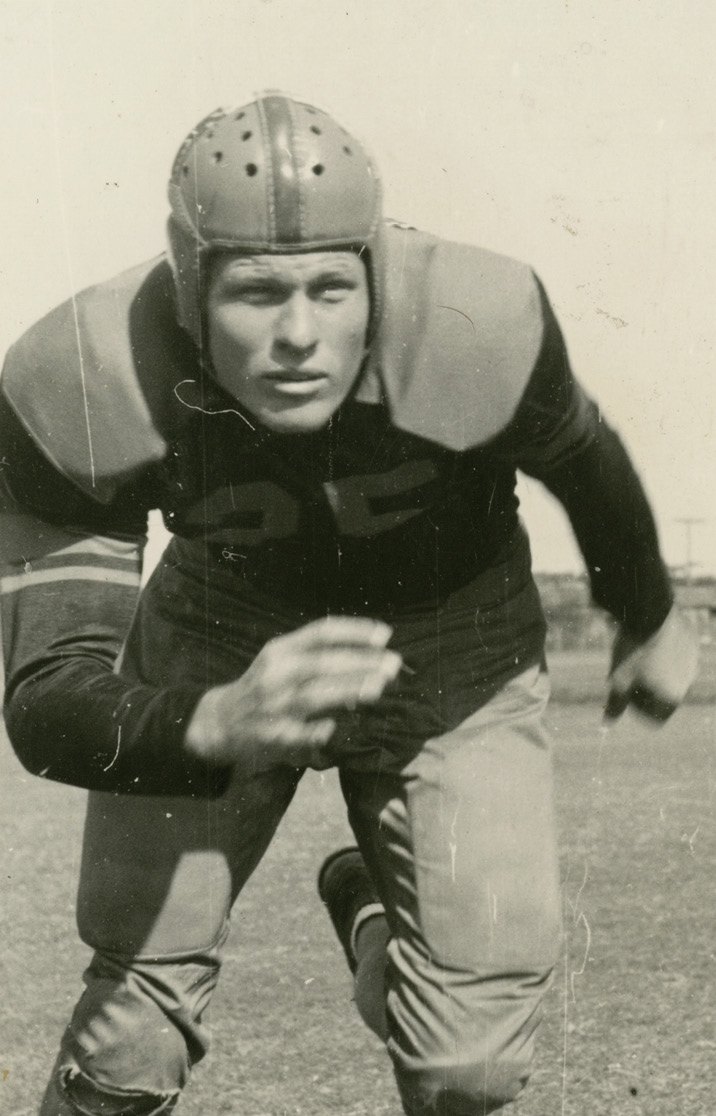

Jack Lummus was a three-time all-Southwest Conference center fielder on Baylor’s baseball team and an honorable mention All-America end on Baylor’s football team. He later played for the NFL’s New York Giants.

Resuming his one-man assault, Lummus killed the second pillbox’s forces and then returned to his men to lead the platoon’s advance. With Lummus at the front, the soldiers again came under fire. Once again, Lummus rushed forward into the open, attacking and killing the enemy in a third fortification.

Richard F. Newcomb’s book, Iwo Jima: The Dramatic Account of the Epic Battle That Turned the Tide of World War II, dramatically conveys what happened next as Lummus led his platoon across the battlefield:

“Suddenly he was in the center of a powerful explosion, obscured by flying rock and dirt. As it cleared, his men saw him rising as if in a hole. A land mine had blown off both his legs. . . . They watched in horror as he stood on the bloody stumps, calling them on. Several men, crying now, ran to him and, for a moment, talked of shooting him to stop his agony. But he was still shouting for them to move out, move out, and the platoon scrambled forward. Their tears turned to rage, they swept an incredible three hundred yards over the impossible ground, and at nightfall were on the ridge overlooking the sea. There was no question that the dirty, tired men, cursing and crying and fighting, had done it for Jack Lummus.”

Lummus was removed to an aid station, where he told the attending doctor, “Well, Doc, the New York Giants lost a mighty good end today.” He died later that day on the field hospital’s operating table at age 29. Lummus was one of 6,821 Marines who died during the Battle of Iwo Jima, which ended March 26, 1945, with a U.S. victory.

“Jack Lummus led alone in combat, so that his men didn’t have to take that type of risk, and he sacrificed his life so his men could fulfill their mission.”

A year later, Lummus was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest personal decoration awarded to U.S. military service members for valor in action. His citation, signed by President Harry Truman, concludes, “He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.” Initially buried on Iwo Jima, Lummus’s remains were interred in 1948 at Myrtle Cemetery in Ennis. On Veterans Day 2005, a monument in Lummus’s honor was dedicated in Austin’s Texas State Cemetery.

Jack Lummus was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for military valor in action. His mother Laura Francis Lummus was presented with her son’s award on Memorial Day, May 30, 1946, in Ennis, Texas, by Admiral Joseph J. Clark.

A Lasting Memorial

The bravery Lummus displayed in battle more than 75 years ago has inspired fellow Baylor alumnus Haag Sherman, B.B.A. ’88, for decades, looming large in his imagination as an example of selfless leadership.

“Jack Lummus led alone in combat, so that his men didn’t have to take that type of risk, and he sacrificed his life so his men could fulfill their mission,” Sherman says. “That quiet competence and selfless nature really resonates with me — that kind of dignified heroism.”

Sherman, who earned a Juris Doctor from the University of Texas at Austin in 1992, recently translated this admiration into public recognition. He and his wife Millette Sherman provided funding and leadership for the design and installation of bronze statues on the Baylor campus that honor Lummus and fellow Medal of Honor recipient John Riley Kane, B.A. ’28.

Kane, who played football and basketball at Baylor, was a colonel in the U.S. Army Air Corps (the precursor to the U.S. Air Force) during World War II. The two Baylor alumni are believed to be the only pair of collegiate letterwinners at any American university to have been awarded the Medal of Honor.

Grace under Pressure

While Lummus made the ultimate sacrifice fighting on the ragged hills of Iwo Jima, Kane’s heroism was displayed in distinctly different circumstances as a pilot in the European theatre of World War II.

John Riley Kane was commander of the 98th Bombardment Group during an attack on a complex of Nazi oil refineries in 1943. He received the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry in action and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

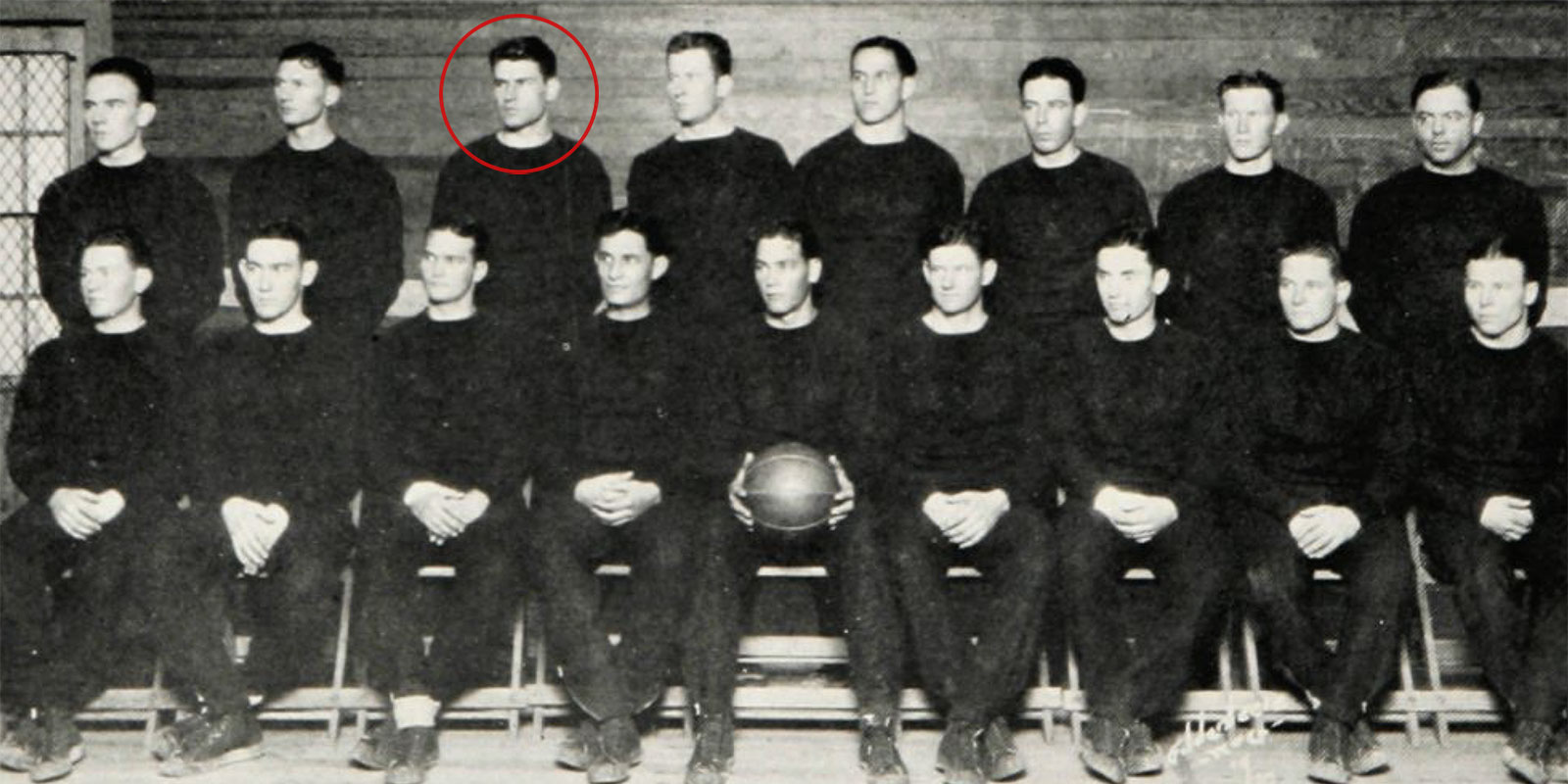

The son of a Baptist preacher, Kane enrolled in Baylor in the fall of 1924 with the aspiration of becoming a doctor — along with developing his skills as a football and basketball player. However, the man who would one day become a decorated war hero almost never lived to see the completion of his studies. He was one of only 12 survivors of the “Immortal Ten” tragedy Jan. 22, 1927, in Round Rock, Texas, in which a train hit the Baylor basketball team bus and killed 10 fellow students.

Kane received his commission in the U.S. Army Air Corps four years after graduating from Baylor. He is described by Leon Wolff in Low Level Mission as a “rough, bruising, hulk of mustached Southerner with a square jaw and icelike eyes.” Kane had a reputation as a fierce, talented combat leader in the Mediterranean, and his actions Aug. 1, 1943, earned him a permanent place in military history.

That was the day of Operation Tidal Wave, a massive bombardment of a complex of oil refineries in Ploiești, Romania, that supplied much of Nazi Germany’s petroleum. The approximately 2,400-mile round trip mission began early in the morning with almost 200 B-24 Liberators departing a base in Libya. Kane was the commander of the 98th Bombardment Group, known as the Pyramidiers, which flew as the third of five bomber groups that were to sweep over Ploiești’s refineries like a tidal wave.

However, problems soon arose. The first two groups were separated from the others in thick clouds and created a 60-mile gap within the formation during the long flight. When the first bomber group arrived at Ploiești, it mistakenly struck the target assigned to Kane’s group — the Astra Romana refinery.

Around 3 p.m., Kane’s men approached their target, skimming the treetops at 250 miles per hour. Despite burning debris, exploding oil storage tanks, delayed-action bombs and a fully alerted enemy, the Pyramidiers never wavered — even as anti-aircraft artillery and wing-destroying barrage-balloon cables took down many planes.

Although his plane, the Hail Columbia, was repeatedly struck, Kane made it through the inferno and circled the bomb site until all of his surviving squad was clear of the fight. Kane’s decision to continue circling spent much of his fuel and caused him to crash-land in Cyprus after nearly 14 hours in the air. He eventually returned to his home base in North Africa.

John Kane (circled) was one of 12 survivors of the “Immortal Ten” tragedy in which a train hit the Baylor Basketball team bus and killed 10 students Jan. 22, 1927, in Round Rock, Texas.

In the end, the bombing raid inflicted a 50 percent destruction of the Astra Romana refinery as well as heavy damage to three other refineries. Those achievements, however, came at a great price. Of the 47 B-24s that Kane led, 18 were shot down in the attack, and only nine of the Pyramidiers’ planes returned safely to their base. In total, 54 of the 178 planes that left on the raid were lost during what proved to be the deadliest air battle in U.S. history.

“I still recall the smoke, fire and B-24s going down like it was yesterday. Even now, I get a lump in my throat when I think about what we went through. I didn’t get the Medal of Honor. The 98th did.”

Nine days after the mission, Kane received the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry in action and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” He was also awarded the Legion of Merit for “personal leadership, foresight, keen judgment, expert planning, outstanding ability.”

After the war, Kane held several stateside commands. In 1947, he was assigned to the National War College at Washington, D.C., where he served until his 1956 retirement. Late in life, Kane told historian Michael Hill, “I still recall the smoke, fire and B-24s going down like it was yesterday. Even now, I get a lump in my throat when I think about what we went through. I didn’t get the Medal of Honor. The 98th did.”

Kane died May 29, 1996, at age 89, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

An Inspiring Story

Those connected to the effort to honor Lummus and Kane at Baylor are pleased with how the project turned out. Created by Dallas-based sculptor Dan Brook, B.A. ’83, both statues feature the men dressed in military uniforms denoting their affiliation and rank.

“When we were looking at photographs of Kane to use as reference for the sculpture, you could see he exuded confidence,” Haag Sherman says. “You could picture him addressing his men before Ploiești, and Dan Brook’s work captures the leadership that provided the impetus for his men to agree to what, in effect, was a suicide mission.”

Like Kane before him, Lummus’s path to Baylor was as a student-athlete. After receiving a scholarship in 1937, he lettered in football and baseball during his years at Baylor. Whether on the gridiron or the diamond, Lummus was a study in speed and strength. He was a three-time all-Southwest Conference center fielder and an honorable mention All-America end in football who “could cover more ground than a six-inch snowstorm,” in the words of one teammate.

After the 1941 baseball season, before graduating, Lummus left Baylor to play minor league baseball with the Wichita State Spudders. He signed a uniform player’s contract with the New York Giants (NFL) that fall and played nine games as a rookie defensive end. Lummus helped the Giants reach the NFL Championship Game, played two Sundays after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. From there, Lummus joined the U.S. Marine Corps and entered into a contest with much greater consequences.

Not surprisingly, the Lummus statue that now stands outside McLane Stadium captures the former athlete’s rugged physique and determination.

“Lummus was a very tall, striking person, and Dan Brook has posed him in his Marine fatigues, with his rifle draped over his shoulder as he embarked on his one-man assault up Mount Suribachi,” Haag Sherman says. “He is quietly confident and gazing forward — just like Michelangelo’s sculpture of David with his slingshot slung over his shoulder.”

Sherman notes that of the more than 16 million men and women who served in World War II, only 464 received the Medal of Honor.

“Having two Medal of Honor recipients, who were also letterwinners, sets Baylor apart,” Sherman says. “Telling the story of these men and their heroism ties into the story of Baylor University’s mission, which is not just about education but also about developing leadership and a commitment to service.”