Fighting Stress in Mind & Body

Baylor researcher builds understanding of stress, the brain and the heart.

When Annie Ginty, Ph.D., shares that her research within Baylor’s Department of Psychology and Neuroscience focuses on stress, the subject’s ubiquity builds an almost instant connection point with others. Most people immediately joke that they would make excellent subjects for her research thanks to the pressures they feel in their daily lives.

Annie Ginty, Ph.D.

“Stress is something that happens in all of our lives,” Ginty says. “It’s a fascinating topic because there are actually big individual differences in how people experience stress and misconceptions about the way it impacts people.”

Ginty, an assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience, defines stress as “when an individual encounters a situation and perceives that they do not have the resources to meet the demands of the situation. At a more basic level, stress is anything that perturbs physiology or homeostasis.”

It is fitting that the definition touches on two distinct but interrelated aspects: an individual’s perception of the stressor and the physical response. The relationship between the brain and the body is recognized but not entirely understood. That intersection is where Ginty has built a burgeoning reputation as a national leader in stress research.

“I look at the ways peoples’ bodies respond to stress and their environment and how that relates to disease outcomes — how it relates to mental health outcomes, cognitive outcomes with aging and cardiovascular health outcomes,” Ginty says. “I want to understand what it is about the way individuals respond that puts them at increased risk for disease or less at risk.”

“During psychological stress, if your heart rate goes up, it’s working harder, but your metabolic system is not changing. There’s an imbalance and a lack of homeostasis that we think is the pathway to cardiovascular disease.”

Specifically, much of Ginty’s work studies the impact of stress on the cardiovascular system. Prior to joining the Baylor faculty in 2016, she was part of a research team at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. The team was the first to demonstrate that an accelerated heart rate response to stress was predictive of mortality from cardiovascular disease.

In 2017, Ginty was named a Rising Star by the American Psychological Association (APA). She earned a K01 Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2019. The highly coveted NIH grant funds her research examining the relationship between the brain’s responses to stress, the potential for cardiovascular disease and developing upstream approaches to mitigate those risks.

“We want to find ways to identify someone in early adolescence or young adulthood and say, ‘You’re at risk for developing cardiovascular disease in your 50s and here is what we need to do now,’” Ginty says. “That is very important.”

Many situations can be stressful: a tough conversation, an unexpected obstacle or a part of the daily grind that regularly elevates blood pressure or heart rate. Part of the reason those situations are stressful is that a person perceives them that way. Stress begins with an appraisal that resources necessary to handle a situation may not be available. Ginty says this impacts the physical response.

“There’s a system-wide response where you have to appraise the situation as stressful,” she says. “Areas of the brain make that appraisal, then communicate with other areas of the brain to send a signal downward for a physiological response, and that leads to a behavioral response. If you feel that it’s stressful, there’s going to be a cardiovascular response to that, and then a behavioral response to cope with the stressor.”

Challenges in untangling that relationship lie in perceptions and individual differences. While most people self-report similar reactions to stress: increased heart rate, sweaty palms or other physical symptoms, the self-report and what scientists actually measure is sometimes incongruent.

Ginty says it’s common to have research participants say they are very stressed. However, when physiological measures are taken, the patients are actually more balanced than they believe. The opposite is also true; individuals who believe themselves to be calm are actually belied by the work their body is doing during stress. Each person has a unique combination of things that he or she finds stressful, more readily manageable situations and unique responses when stress arrives.

“There are appropriate reactions to stress,” Ginty says. “For example, when people exercise, their heart rate goes up and their metabolic system also responds. Exercise is stress, but it’s a good stress — everything is increasing, so there’s balance. During psychological stress, if your heart rate goes up, it’s working harder, but your metabolic system is not changing. There’s an imbalance and a lack of homeostasis that we think is a potential pathway to cardiovascular disease.”

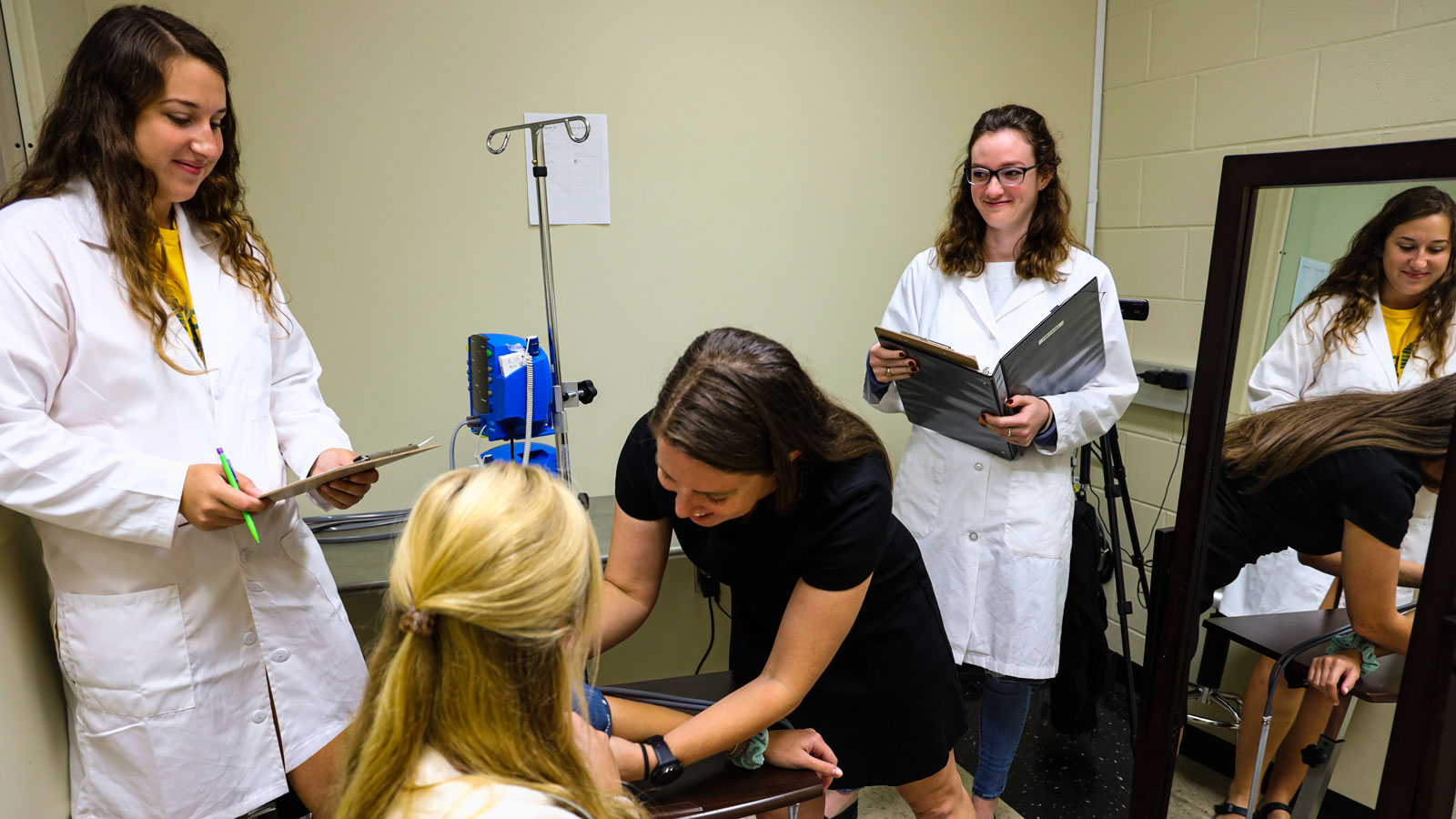

Researchers need a balanced baseline to quantify stress for an individual and have a variety of resources to deploy to measure the cardiovascular system at rest and under stress. Electrocardiogram tests provide insights into heart rate and the amount of blood the heart pumps. Saliva samples are utilized to measure the stress hormone cortisol. Neuroimaging equipment scans the brain. The results of the tests both at rest and under stress are compared to paint a more complete picture of an individual’s baseline and stress response.

Even with those tools, much of the research in the field only shows a correlation. In her NIH-funded research, Ginty advances past approaches by using additional resources to measure the peripheral physiology system, cardiovascular system and brain — a novel combination of study that few researchers have yet tackled. She will be the first to use laser stimulation of the brain to see how it impacts the heart’s responses to stress.

“There’s very little work that actively aims to alter one part of the physiology to see if it changes the other,” Ginty says. “We’ll utilize transcranial infrared light laser stimulation on areas of the brain we know to be associated with stress and measure the efficiency of brain functioning. It’s all external. From there, we will measure the physiological change and look to answer whether or not we can treat at the level of the brain to change the physiological level and thereby reduce disease risk.”

Other projects in Ginty’s highly active Baylor Behavioral Medicine Laboratory focus on the impact of interval training on stress. Prior research that informs the discipline found that interval training positively impacts the brain for up to eight hours after activity. She also studies individuals who display a blunted response to stress. Research shows it can be as harmful as overreacting.

While the research is at a high level, Ginty and her student lab members approach practical, people-centered solutions. They have produced a series of videos on stress management for college students, and they have partnered with local organizations like The Cove, where they work with teenagers battling homelessness or other home-related challenges.

Ginty is the only member of her team recognized as an APA Rising Star, but she may not be the last. Earlier this year, two of Ginty’s students published a paper on habituation in the International Journal of Psychophysiology.

Fourth-year Ph.D. student Alex Tyra was the article’s lead author. Her team studied reaction styles over repeated exposure to stress rather than a single stressor.

“This is important because it’s more like what we experience in daily life — the same stress over and over again,” Tyra says. “Habituation is the sense that when you sense a stressor, you might engage all of your resources to respond in the beginning. Over time, you don’t need to engage as much, and your body doesn’t respond as dramatically anymore.”

Samantha Soto, a senior neuroscience major and Baylor McNair Scholar, partnered with Tyra on the paper. They examined perceptions of a person’s response to stress and measured it against physiological data.

“We found that higher frequency of stress was related to less habituation of heart rate responses,” Soto says. “If you experience a greater frequency of stressful events in your life, you are less likely to habituate.”

Their research found a deviation from previously published research.

“We found that stress frequency was more indicative of heart rate and blood pressure,” Tyra says. “The amount of stress you experience matters more than your actual perceptions of the stress itself.”

The picture painted by their research lives out a part of what drew Ginty to join the Baylor faculty in the first place — support for research along with the opportunity to work with students along each step of the college journey.

“I really fell in love with the idea that Baylor was giving me an opportunity to invest in high-level research and that the University also values the importance of mentoring undergraduate students,” Ginty says. “That’s something you can’t do everywhere. Our partnership with The Cove is another example. At a lot of places, there’s a sense of ‘just focus on your research.’ In Baylor, I saw that they were committed to me as a researcher but also valued utilizing that research for service.”

Such partnerships add community-minded dimensions that ensure both students and the community benefit beyond the laboratory. Ginty’s work helps propel Baylor’s pursuit of Tier 1/R1 research recognition through the framework of Illuminate.

“The NIH recognized Baylor’s commitment to junior researchers like me as a major factor in presenting the award,” Ginty says. “Baylor is committed to junior researchers and provides support for our careers. NIH saw Baylor’s investment in health research through Illuminate and thought highly of that. To have the opportunity to do this kind of work at a place that allows it all to happen is really incredible. To bring it all together to make an impact for others is what’s really exciting.”