The Art of Diplomacy

After more than three decades in the U.S. Department of State, including two Middle East ambassadorships, Doug Silliman, BA ’82, was named president of the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington last year. His career reflects the words in Baylor University’s mission statement: “… to educate men and women for worldwide leadership and service …”

Most Americans who were beyond the age of cognizance that morning know exactly where they were and what they were doing Sept. 11, 2001. Silliman was in Amman, Jordan, roughly a year into his position as political counselor at the U.S. Embassy. Edward “Skip” Gnehm recently had been appointed ambassador and had reported to the embassy the previous day.

Gnehm hosted a reception for embassy employees at his house the afternoon of Sept. 11. The event began at 4 p.m. in Jordan — 9 a.m. in New York City. Silliman was finishing things in the office when news reports of the World Trade Center attacks appeared on the television. He called Susan Ziadeh, who at the time was the Jordan desk officer in Washington.

“Susan’s office overlooked the Potomac River and the Pentagon from the State Department,” Silliman says. “We were talking about what was happening when the alarms in her building started going off.”

Seconds later, while still on the phone with Silliman, Ziadeh watched from her office window as American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon.

Silliman was able to contact his wife Catherine and sons Zachary and Benjamin, all of whom were with him in Jordan. Then, after locating all staff, securing the U.S. facilities in Jordan, and warning American citizens in the country, Silliman began working with Gnehm to set up a traditional Arabic Bedouin tent in the U.S. Embassy parking lot. Their effort was to reach out to the Jordanians by having the equivalent of a culturally appropriate wake.

“We were truly surprised by the response,” Silliman says. “Literally busloads of Jordanians came to offer condolences and say what a horrible thing this had been and that the United States needed to understand that this did not represent Islam or Arabic culture.”

The makeshift wake at the embassy lasted for three days, 10 hours each day. Silliman says a steady stream of Jordanians visited, kissed their cheeks, drank small cups of tea or coffee and went on their way.

“I was impressed — surprised but impressed — by the outpouring of real sympathy from Jordanians for what had happened in New York,” Silliman says. “It didn’t lessen the impact of 9/11 for me, but it gave me some hope that this did not represent the views of all Arabs or all Muslims for the United States.”

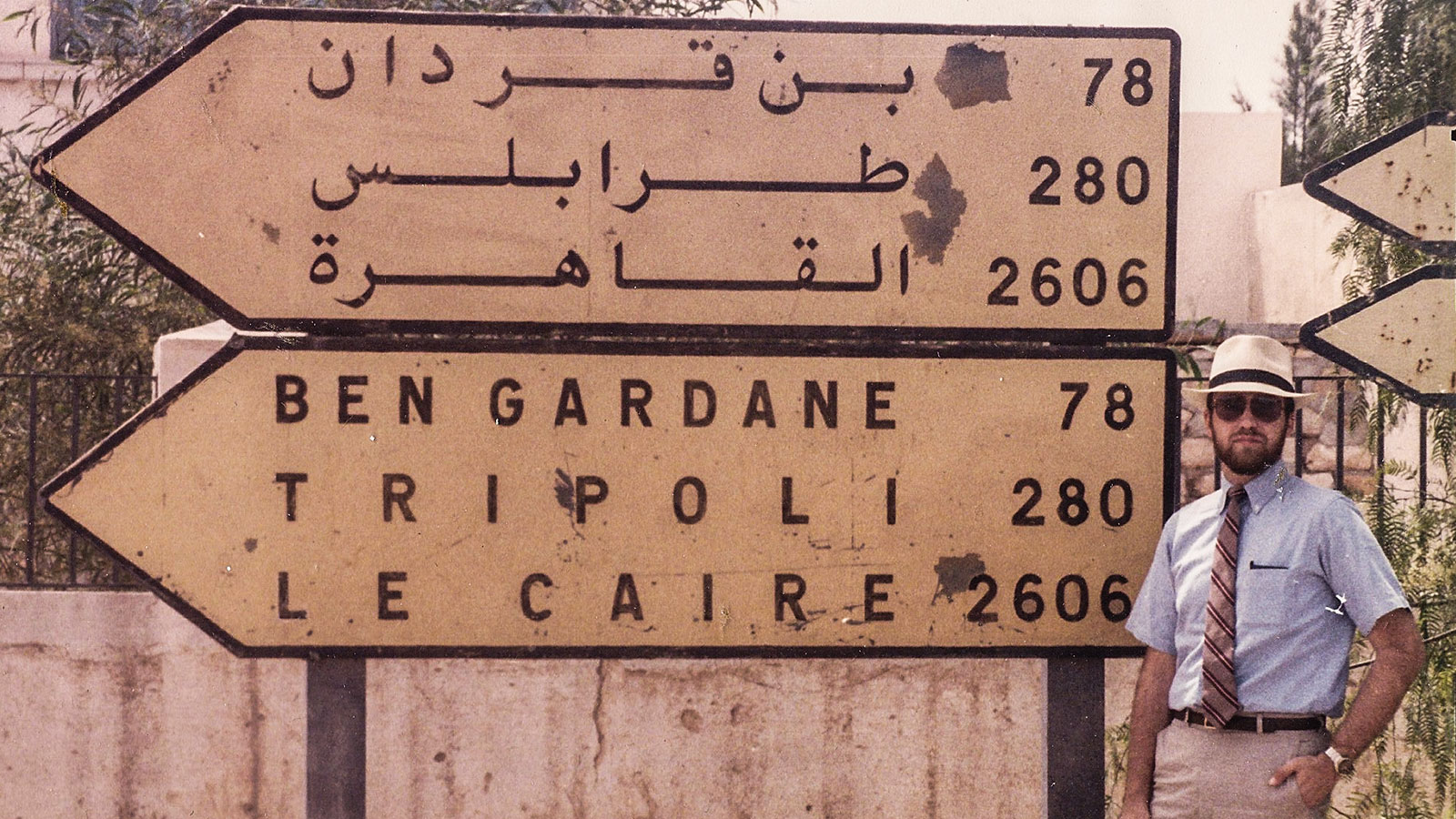

Silliman was by no means new to the Middle East, Muslims or Arabic culture. He joined the State Department in April 1984 and earned a Master of Arts in international relations from The George Washington University in February 1985. After a stint as a visa officer in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Silliman moved to a political officer role in Tunis, Tunisia. He subsequently was staff assistant to the assistant secretary for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, the Lebanon Desk Officer and in the Office of Soviet Union Affairs.

From 1993 to 1996, Silliman was a political officer in Pakistan before being named regional officer for the Middle East in the Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. The beginning of his time in Pakistan coincided with Benazir Bhutto’s election as Pakistan’s first female prime minister.

Silliman remembers being hopeful that Bhutto’s election would solidify around a more liberal vision of the country’s future and improve its relations with India. Instead, he witnessed the reality of Pakistani politics. Silliman ultimately saw Bhutto and her family as representative of 14th century feudalism, while Nawaz Sharif (her main political opponent) represented 19th century capitalism and industrialization — “in the bad kind of way,” Silliman says.

“You had two very different economic systems, two very different powerful families and political parties who saw the country entirely differently,” he says. “They took politics a couple steps beyond what they needed to, to the extent that they each put the other in jail when they were no longer in office, which only exacerbated the differences and made the two parties less likely to cooperate with each other.

“There was enough criminality and corruption on both sides to go around, but I think it was probably a mistake on both sides to try to punish the leadership of the other party when they were out of power rather than trying to find some accommodation.”

Silliman says his time in Pakistan was a good learning experience for his future work in the Middle East but for unfortunate reasons. At approximately 9:30 a.m. Nov. 19, 1995, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad carried out an attack on the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan, roughly a quarter mile from the American Embassy.

“This is how Ayman al-Zawahiri introduced himself to Osama bin Laden,” Silliman says. “At that point, he was hiding in the mountains in Afghanistan. They linked up and became the nucleus of what was then Al-Qaeda. What we saw was that extremist Islamist terrorists from the Arab world had infiltrated into Pakistan and had radicalized a lot of the marginal Pakistani opposition and some of the Muslim opposition in India to the government.”

According to Silliman, Muslim militants previously would kidnap people in the mountains and hold them for ransom and occasionally kill them. Things worsened.

“You began to see hikers of indeterminate nationality captured, killed, and had their hearts taken out and political slogans carved into their bodies,” he says. “A totally more brutal and radical kind of terrorism that we were quite sure had been brought in by some sort of the Arab extremists.”

Soon thereafter, Silliman returned to the United States as regional officer for the Middle East in the Office of the Coordinator of Counterterrorism. In this role, he helped Congress shape the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996.

“All of that very much got me into the history, the ideology, the personalities, the methodologies of Middle Eastern terrorists,” he says. “Iranian, Persian, Arab, Kurdish and others. It was an unfortunate segue, but it was a good introduction.”

How To Grow A Diplomat

Silliman, whose father was in the oil business, considers himself tri-coastal. He was born near San Francisco and moved to Houston in grade school. His career began in the Washington, D.C., area, and he and his wife now have a house in Maine. Silliman says his time in Texas gives him a different perspective from many of his colleagues.

It was in Texas — at Cypress-Fairbanks High School — that his path to a career in foreign service began. Silliman took three years of Latin at Cy-Fair, but the school’s Latin teacher, Caroline Hynes, had different plans for his Latin IV course.

“She said, ‘Well, you’re the only Latin IV student. Sign up for it, and I’ll give you A’s, but you’re not going to take Latin,’” Silliman says.

Instead, Silliman assisted Hynes in teaching her English as a Second Language class, which included students of Russian, Palestinian, African and South American heritage.

“We taught them English when there was no common language among them except English,” he says.

Near the completion of the course, Hynes told Silliman that he would one day work for the State Department. He asked if she meant the Texas State Department of Transportation or Public Safety, but Hynes quickly pointed him toward Washington. He found it to be an intriguing idea.

“Mrs. Hynes and her husband paid for me to go on a three-week, all-expenses-paid trip through Europe after my graduation because she had so much faith in me that I could do this well,” Silliman says.

The trip was eye-opening for Silliman, who envisioned himself working in international relations but more so in a cultural sense. His mother was a pianist and introduced him to 19th-century Russian music. He was fascinated with Russian culture and delved into it at a young age.

“From early on, I had the bug that I wanted to explore and see other cultures and other parts of the world,” Silliman says. “But it was Caroline Hynes, my high school Latin teacher, who melded those two together and defined a path for me to accomplish that in my life.”

From there, Silliman’s path led to Baylor. He was introduced to the University through high school debate team competitions held on the Baylor campus.

“I felt very comfortable at Baylor, and I wanted to go close to home but not too close to home,” he says. “I really liked my experience.”

Silliman was drawn to Baylor due to a then-recent broadening of the University’s Christian missionary program into what he describes as a “foreign service, international business, international journalism” program.

“At that point, it was one of the few programs and schools I was looking at that met the requirements I felt I needed to be a diplomat in the future,” he says. “It looked at religion and culture and language and politics and economics. It was more than a straight political science course.

“I came to Baylor because it was a well-rounded interdisciplinary program. That’s a real strength of the University.”

Silliman valued developing relationships with several professors, including his advisor Lyle C. Brown, who directed the foreign service international business and Texas politics programs. Longtime U.S. State Department geographist Colbert C. Held, BA ’38, was Baylor’s Diplomat-in-Residence during Silliman’s enrollment. Many years later, one of Held’s daughters and Silliman served together in Iraq.

“There are very few places at a school that is as large and important as Baylor where you have the opportunity to go to a professor’s house and have dinner with his family in a small group and learn what the professor’s path was to whatever topic he or she ended up teaching,” Silliman says. “It was the real strength of Baylor 35 years ago, and I suspect it’s still the same today.”

Silliman’s career began in the waning years of the Cold War. His love of Russian history and culture led to a focus on Soviet diplomatic politics in graduate school at George Washington.

“I wanted to better understand what made the Soviet Union tick,” he says. “So, of course, when I joined the State Department, they sent me to Haiti for my first tour and taught me French. That’s one of the things that is really interesting about how the U.S. government works in the military, in foreign service: No matter what you’ve done in the past, they put you wherever there is an opening.”

Later in his career, Silliman had the opportunity to put his Russian acumen to work. He served on the State Department’s Soviet desk during the coup against then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Prior to the Soviet Union’s collapse, Silliman says, diplomacy involved the reading of talking points, a handshake and nothing further.

“It was very formalized,” he says. “I was there after the Soviet Union fell apart. I’d go to the new Russian embassy, and they’d bring out the vodka and black bread and pickled mushrooms, and we’d sort of have an informal party. Then, we’d just talk.

“Studying the Soviet Union and working on it when the Berlin Wall fell and when the Soviet Union collapsed, and then going back to see the new states of the former Soviet Union was absolutely fantastic. It felt like coming full circle from my youth and my education.”

Clockwise from upper left: Silliman and U.S. Vice President Mike Pence welcome then-Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi for a March 2017 breakfast at the Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C. Silliman meets with Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad Al-Sabah, the Amir of Kuwait, in 2015. Silliman and then-U.S. Vice President Joe Biden at the White House in 2016. Silliman holds a press conference at the St. Hormizd Chaldean Monastery in Northern Iraq.

An Appreciation for the Past

In 2008, after a three-year stint in Washington, Silliman returned overseas to Ankara, Turkey, as the deputy chief of mission — the No. 2 diplomat assigned to an embassy. He became charge d’affaires — the acting ambassador -— for much of 2010. Silliman moved to Baghdad in 2011 as political minister counselor, and he stayed on for a second tour of duty in Iraq as the deputy chief of mission. In 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama named Silliman as U.S. Ambassador to Kuwait. Silliman chose Joey Hood as his deputy chief of mission.

“We got off to a great start together, and I felt I had won the lottery in terms of bosses,” Hood says. “He pays a lot of attention to making sure people are treated right. To me, that’s the gold standard. If you have that as your foundation, you can get anything done and survive any kind of crisis.”

Silliman quickly learned there was a lack of understanding and historical appreciation for America’s role in Kuwait’s 1991 liberation from Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces that invaded the Persian Gulf country the previous summer.

“We found the government really didn’t want to talk about the Gulf War,” Silliman says. “The day I arrived in Kuwait, on my desk, there were three Kuwaiti school textbooks in Arabic with sticky notes on a couple of pages. In the education system, Kuwaitis don’t mention the United States when they talk about the liberation. The books essentially said, ‘In August 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and a coalition of Kuwait’s friends and partners liberated the country.’”

With the 25th anniversary of Kuwait’s liberation approaching, Silliman saw an opportunity to address the knowledge chasm.

“I heard too many stories, even in my first weeks, from Kuwaiti friends, Kuwaiti businesspeople, about how much Kuwaitis appreciated the United States, which is not something you hear all the time in the Middle East,” Silliman says. “I had people coming up to me in shopping malls and on the streets and in restaurants, and they said, ‘I want to thank your country for saving my country.’”

Silliman and Hood worked with Kuwait’s minister of information and U.S. veterans’ organizations to coordinate commemorative 25th-anniversary events. As part of the effort, information was taken into the schools and shared with children who had no previous knowledge of what happened a quarter century earlier. Additionally, Silliman’s father-in-law, who was in the U.S. Army Medical Corps during the Gulf War, attended the celebratory events, and his uniform is now displayed in the Kuwait War Museum.

“It was personal for me, but it was also emotional,” Silliman says. “I wanted to make sure that Kuwaitis could articulate what the United States and other countries that participated in the coalition to liberate Kuwait actually did. I wanted to make sure Kuwaitis were not afraid of telling their own stories of life under occupation or life running intelligence missions into and out of the country. It was important and cathartic for the Kuwaitis to do this.”

In 2016, Silliman was named U.S. Ambassador to Iraq. Although he had two previous tours in Baghdad under his belt, Silliman faced new challenges in the war-torn country.

“The first one was a security challenge, but it wasn’t necessarily because people were always trying to kill me,” he says. “By trying to gauge how much risk there was in various things I wanted to do, I was able to work with my security people and find ways to be safe but to get out to talk with people, to visit sites that hadn’t been visited in a long time.”

Silliman visited Mosul, a city of more than 2 million inhabitants before being occupied by ISIS, a week after its liberation. The Battle of Mosul, which ended in July 2017 when Iraqi forces basically bulldozed the final 10 acres of the dense city center on top of ISIS fighters, is widely considered the largest urban battle since the Battle of Stalingrad during World War II.

“We were able to visit — while there was still stray sniper fire around — to see what had happened at the end of the battle,” Silliman says. “Seeing the immediate aftermath was something that has stuck with me quite a lot.”

Silliman departed Iraq in January 2019 and retired from the Foreign Service a few months later after 35 years and two days of service. However, he did not leave the Middle East. In June 2019, he was named president of the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (AGSIW). Hood says Silliman is ideal for the role.

“Doug is a sharp analytical mind,” Hood says. “He will be able to write and speak about issues that are important to the Institute with eloquence and clarity, as well as with a deep background in the region. His experience in the U.S. foreign service is truly unique.”

AGSIW consists of four in-house scholars along with more than 30 scholars at U.S. universities, in the Middle East and in Europe. They are charged with analyzing the political, social and economic climate in the Middle East and sharing their findings with all interested parties. This takes many forms, including speaking at universities as Silliman did at his alma mater in late October 2019.

In his new role, Silliman continues to struggle with questions of war and peace in the Middle East, particularly in Iraq. Silliman says the larger challenge, however, is getting Iraq to focus on the future, learning how to maintain one of the world’s great ancient civilizations and make it work for the next generation.

“It’s going to be difficult,” he says. “When we invaded Iraq and pulled down Saddam Hussein, that opened up all of the old fissures in society: Sunnis vs. Shiite, tribal vs. city, educated vs. uneducated, Kurds vs. Arabs, Christians vs. others. Today, the government has become, unfortunately, very corrupt and incapable of making meaningful reforms.”

What concerns Silliman most in Iraq is the nearly 1 million young Iraqis who every year graduate from high school or college and expect the government to give them a job — only to find that the government is incapable of producing that many jobs.

“The government makes it almost impossible for an entrepreneur to have a productive small business,” Silliman says. “Industries are all run by the government. It still is a truly socialist economy. I think this is going to, in the end, destabilize Iraq and make more significant social and economic challenges.”

Shortly after Silliman’s visit to Baylor in October 2019, tens of thousands of the disaffected Iraq youth that he talked about poured into the streets to force the government to lessen foreign — especially Iranian — influence, and to implement reforms that would give them a better future.

“Despite violence by government forces and pro-Iranian militias against the demonstrators, nearly three months, 15,000 injuries and 500 deaths later, youth continue to press the Iraqi government for real reform,” Silliman says.

For more information on the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, visit agsiw.org.