Illuminating the Sacred

Art historian provides biblical context and insight for centuries-old masterpieces.

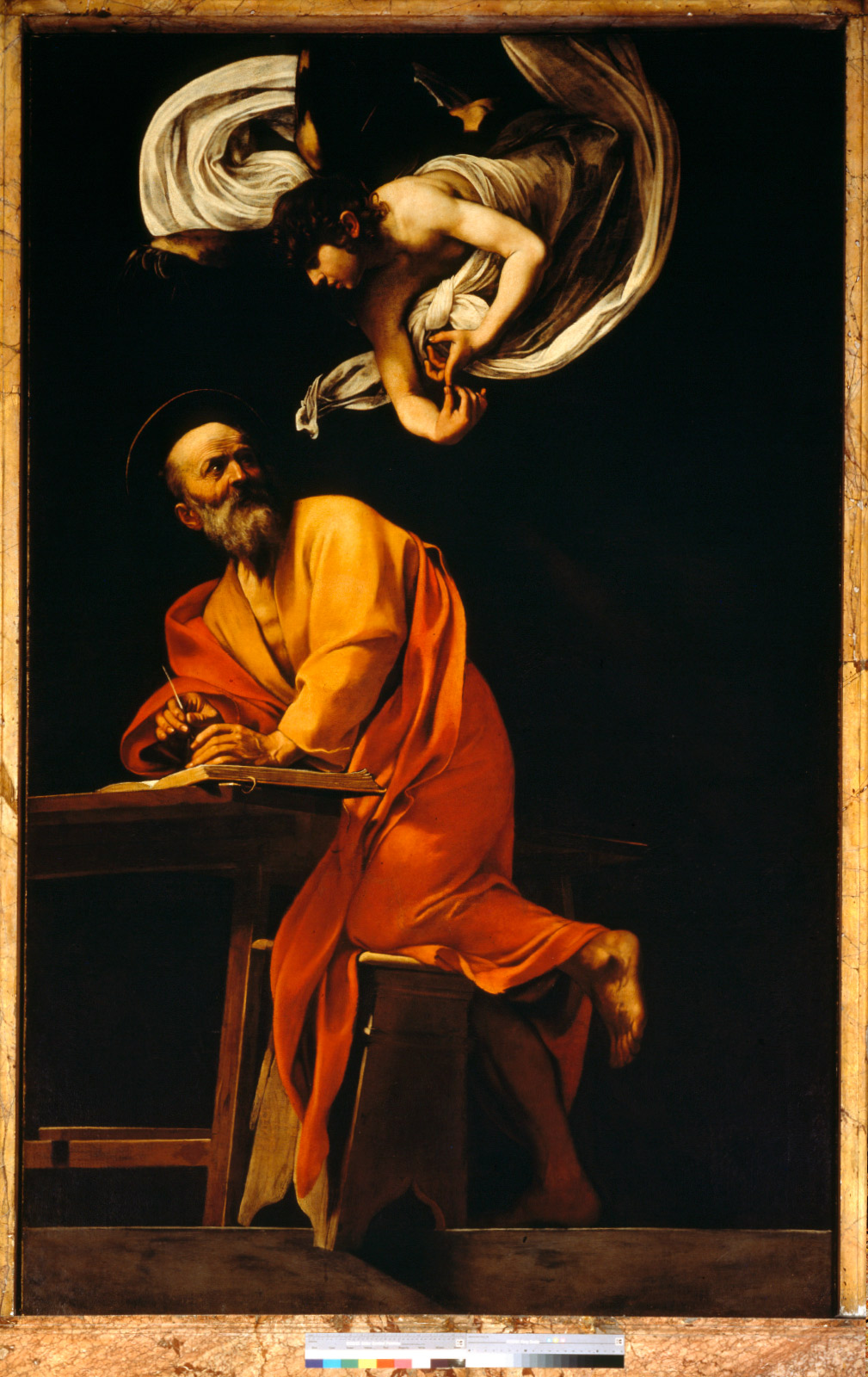

In 1599, Italian master Caravaggio created Saint Matthew and the Angel, a celebrated painting that students, scholars and experts continue to study in its original location and alongside two other works by the artist in the eternal city, Rome.

The stunning subject matter pays homage to the inspired writing of its namesake gospel, depicting the saintly writer at work while a literal seraph gently guides his hand.

“It is Caravaggio’s way of trying to explain what it was like to be divinely inspired,” Baylor professor Heidi Hornik says. “When we look at these themes, it causes us as art historians to ask ourselves, ‘How do we talk about scripture? How do we make them real for all kinds of Christians?’”

Saint Matthew and the Angel, commissioned by the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome for the iconic Contarelli Chapel, is one of the many works featured in Dr. Hornik’s recently released book, The Art of Christian Reflection.

“The only way to teach well in art history is to research. For us, research includes going to museums and standing in front of the works of art or going to buildings to study the architecture—interior and exterior,” she says. “Professors are most inspired when their research makes it into the classroom.”

Last fall, she taught an upper-division seminar in which the subject was Mannerism and included the 16th-century Florentine painter Michele Tosini. Her latest scholarly work on the artist punctuated the in-depth study.

In writing one of the curriculum’s primary texts, Hornik found herself deep in the archives studying Tosini’s last will and testament, along with other historical documents, and piecing together the first book to showcase the complete life of the Italian Mannerist.

More than three-quarters of the full-capacity class were repeat students, eager to learn more and captivated by Hornik’s teaching. When the day’s course time ended, students often lingered to ask questions and explore prompts initiated in her lecture materials.

“These are the kinds of classes that [produce] undergraduate theses and independent studies,” Hornik says. “Our scholarly research for undergraduates is exactly motivated by those kinds of classes.”

Senior studio art major Eden Guild says Hornik’s classes are among the most challenging and rewarding classes she has taken at Baylor.

“The lectures, readings and research in Dr. Hornik’s classes become engaging narratives that students get to experience,” Guild says. “The information we read in textbooks comes to life. Dr. Hornik has an incredible amount of work outside of teaching, but she is present and fully engaged in class—always captivating students with new information and igniting sustainable interest in the art historical world.”

Two University Scholars (Nathan Eberlein, BA '17 and Conner Moncrief, BA '16) in Dr. Hornik's class on Connoisseurship examine a 14th-century Madonna and Child painted by a follower of the Sienese artist Pietro Lorenzetti in the Armstrong Browning Library Collection. The Connoisseurship class was held in the Armstrong Browning Library in front of the 15 original works of art from 1330-1750. The Madonna and Child here is removed from the wall to investigate not only the condition of the work (i.e. insect presence, paint deterioration) but also to measure the punch marks in the Virgin's gold-leaf halo. The punch marks are, in effect, a type of signature for a particular painting workshop during this period and assist in formulating accurate attribution.

Hunter Ash, BFA ’18, describes Hornik as a professor who is encouraging and passionate with the additional benefit of being a delightful person. Twice, Ash structured her schedule around Hornik’s class availability.

“I especially appreciated Dr. Hornik’s ability to make art history subjects relevant and relatable,” Ash says. “She challenges students to think like art historians, ask hard questions and remain curious about what is still to be uncovered in the world of art history.”

Hornik notes that she and her colleagues intentionally dedicate their teaching energies toward undergraduates, offering the kind of transformational education laid out in Baylor’s Illuminate academic strategic plan.

“Art history at the undergraduate level is highly analytical, and it bodes well for clear, critical thinking,” she says. “To get those students at a young age excited and thinking critically about not just words, but pictures and sculptures and architecture, it changes their awareness, appreciation and comprehension of the world around them. Developing those kinds of skills between 18 and 22 can only enhance whatever you do from 23 on.”

Junior marketing major Katie Burton says Hornik encourages students to learn the context behind the art and that the professor’s love of the material radiates in her lectures.

“She wants to share this excitement and love of art with her students,” Burton says. “Dr. Hornik transforms the nature of undergraduate education by giving students in-depth, original research opportunities that would typically be seen in graduate-level classes. Her expertise is made clearer when she passes down the information she has worked hard to acquire.”

Senior art history major Emily Starr was Hornik’s research assistant while the professor was a visiting scholar at Harvard. Starr says Baylor is fortunate to have an instructor of Hornik’s ilk.

“Dr. Hornik expects a lot of her students,” Starr says. “She’s the mother of two college-aged sons, so she’s not foreign to the lives of college students. As inspiring and professional as she is in the classroom, she’s also really approachable with what we are going through in our other classes. She wants her classes to be transformational, but she also wants our education to be well-rounded.”

By Hornik’s admission, the late ’80s version of herself would have difficulty envisioning her as an author of a book on Christian ethics or living in Central Texas.

Her undergraduate years at Cornell University initially focused on engineering, although she had participated in a student trip to Italy while in high school.

“Dr. Hornik transforms the nature of undergraduate education by giving students in-depth, original research opportunities that would typically be seen in graduate-level classes.”

“I really liked civil engineering, which is predominately architecture and the building of things,” she says, noting that she changed majors after 2.5 years to pursue studies on Italian Renaissance and art history. “I had a knack for it. I knew I wanted to focus on the Italian Renaissance. I really liked Christian art. The Renaissance is the most prolific with religious art.

“But, I also loved Florence, and I loved Italy,” Hornik says.

Her accomplished career started almost three decades ago with what she calls a great first job. Hornik arrived at Baylor’s Department of Art and Art History soon after completing her PhD (and MA) at Penn State University. She recalls the interview with Baylor professors John McClanahan, Bill Jensen and Paul McCoy at a College Art Association meeting in New York City.

“I had a good feeling about what they had to say. I liked the idea that this was a Christian university. So, I came down to Texas, and Paul [McCoy] picked me up in a pickup truck. Kind of a new experience for a New Yorker,” Hornik says with a laugh.

Three years later, Hornik crossed paths for the first time with someone who would deeply influence her personal life. And together they would develop additional and collaborative avenues for their research areas.

In 1993, at a steering committee meeting for the then-fledgling Baylor Interdisciplinary Core curriculum, Hornik met Dr. Mikeal Parsons, a professor in the University’s Department of Religion. They married in 1995, raised two children, and traveled the world together.

Caravaggio's Saint Matthew and the Angel was commissioned by Cardinal Matthieu Cointrel (who Italianized his name to Matteo Contarelli) for his iconic chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

Estimating her sons to have spent “two-thirds of their childhood summers” in Italy, Hornik and most often her family would travel to Florence—sometimes for weeks, others for months—at least once annually on average. There, she could research, teach and immerse herself in the epicenter of her expertise.

Parsons says the summers spent abroad had a lasting impact on their sons, both of whom are Harvard students. Their younger son, Matthew, plays clarinet in Harvard’s Bach Society Orchestra.

“He discovered his musical talents as a 6-year-old at the Barton School while we were on sabbatical leave in Cambridge, England,” Parsons says. “He is pre-med but earning a second major in Italian language and culture—a direct result of our summers in Italy.”

Their older son, Mikeal, is an economics major and an art history minor.

“Again, an obvious indication of the benefit of international travel, not to mention the influence of his mother,” Parsons says.

Hornik and Parsons also formed a professional collaboration that showcases their individual research strengths.

“When we got married, we wanted to find a way to have our disciplines overlap,” she says. “You look at Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus: Why the supper at Emmaus? Why did Caravaggio interpret it that way? The scholarship came from a desire for both of us to be working on a similar project and—for me in particular—to continue my work overseas in Florence.”

They utilized the concept of “biblical reception.”

“There isn’t really a category for biblical reception in art history. For the most part I’ve taken art historical training and methodology and applied it in ways that are desired by biblical scholars and respected by art historians,” she says. “Art historians are always doing iconography, but not with so much emphasis on the Bible. They may read Matthew 16:18-19, possibly cite it for apostolic succession, but they won’t look at it asking ‘how did Perugino, in the Giving of the Keys in the Sistine Chapel, depict that scene so precisely according to biblical narrative?’”

Over the past 15 years, Hornik and Parsons have co-published a number of interdisciplinary, scholarly works blending art and theology. Most notable among these works is a multi-part, in-depth analysis of the Book of Luke and many of the Italian Renaissance pieces that the gospel’s texts inspired.

“Researching and writing with Heidi has always been rewarding, professionally and personally,” Parsons says. “Her breadth of knowledge across the history of art is remarkable. These shared intellectual interests add a dimension to our relationship that few couples get to experience.”

Hornik values opportunities to work with her husband and collaborate with others; however, she relishes creating independent work that expands her experience and adds to the richness of knowledge she readily shares with her students.

“Her breadth of knowledge across the history of art is remarkable. These shared intellectual interests add a dimension to our relationship that few couples get to experience.”

The Art of Christian Reflection in many ways reflects her academic and personal progression, Hornik says.

Released in October through Baylor University Press, The Art of Christian Reflection delves into some of the most relevant and mysterious issues connecting traditional artwork with the essential virtues of Christianity.

In it, more than 80 different masterpieces—paintings, sculptures and architecture—illustrate an erudite labor of love from the internationally recognized scholar and professor. Accompanied by a thoughtful narrative and strong scriptural backbone, Hornik takes readers from the third century to the 20th century to discover why the works created in those eras continue to resonate and challenge us today.

In the conceptual stages of the book, Hornik drew on some of her earlier work in Christian Reflection, a quarterly project of Baylor’s Institute for Faith and Learning produced from 2000 to 2016. Hornik, a regular contributor to the series (circulation estimated at about 8,000), found herself being shaped and formed by the thematic assignments she was asked to “bring alive” in the publication.

Revisiting the essays—some almost 20 years old—brought her once again to the conclusion that the issues at the heart of art and religion rarely change over time. They are simply reborn to bring about new and important conversations with each successive generation and the social issues that go along with them.

Giotto's Lamentation (1305-1306) illustrates one of the issues facing contemporary Christians today, Women in the Church, that is discussed in the second section of Hornik's The Art of Christian Reflection, Five women grieve over the body of Christ in this fresco painting from the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy. The elaborate fresco cycle depicts nineteen scenes from the life of Christ and the same number from the life of Mary, his mother. The presence of the women in this visual tradition reminds us of the importance of women in the gospel accounts of Christ's life (here at the Crucifixion and the Entombment) as well as in related Apocryphal stories such as the Lamentation

“Our current culture is thinking a lot about ethics,” Hornik says. “Whether it’s politics or war or the raising of children in this particular day and age, the hope is that these areas of the book would help incorporate some of the positive things [reflected in the art] into a discussion that make it real and pertinent to daily life.”

So pertinent are the topics and images inside The Art of Christian Reflection, that the book was chosen for review at a session of the American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature’s 2018 annual meetings, an event held last November in Denver and attracting an attendance of around 10,000, making it the world’s largest single-location gathering of religious scholars.

“The review panel, with responses from two senior female colleagues who have been mentors and friends, and two Christian Reflection series editors, was truly rewarding and humbling,” Hornik says. “The session, like the book itself, was personal, reflective, scholarly and transformative for me as a scholar and as a Christian.”

One of the reviewers, Dr. Robin Jensen of Notre Dame, likened the content of Hornik’s book to Ignatian contemplation as it encourages meditation on biblical narrative as the core of the contemplative practice. Jensen encouraged Hornik to write a sequel using additional themes and works of art, including more contemporary art.

For Hornik, a high school social studies trip to Italy blossomed into a love affair with the country, art history and—fortunately for Baylor colleagues and students—an indelible career as a professor and researcher.