Excavating Music History

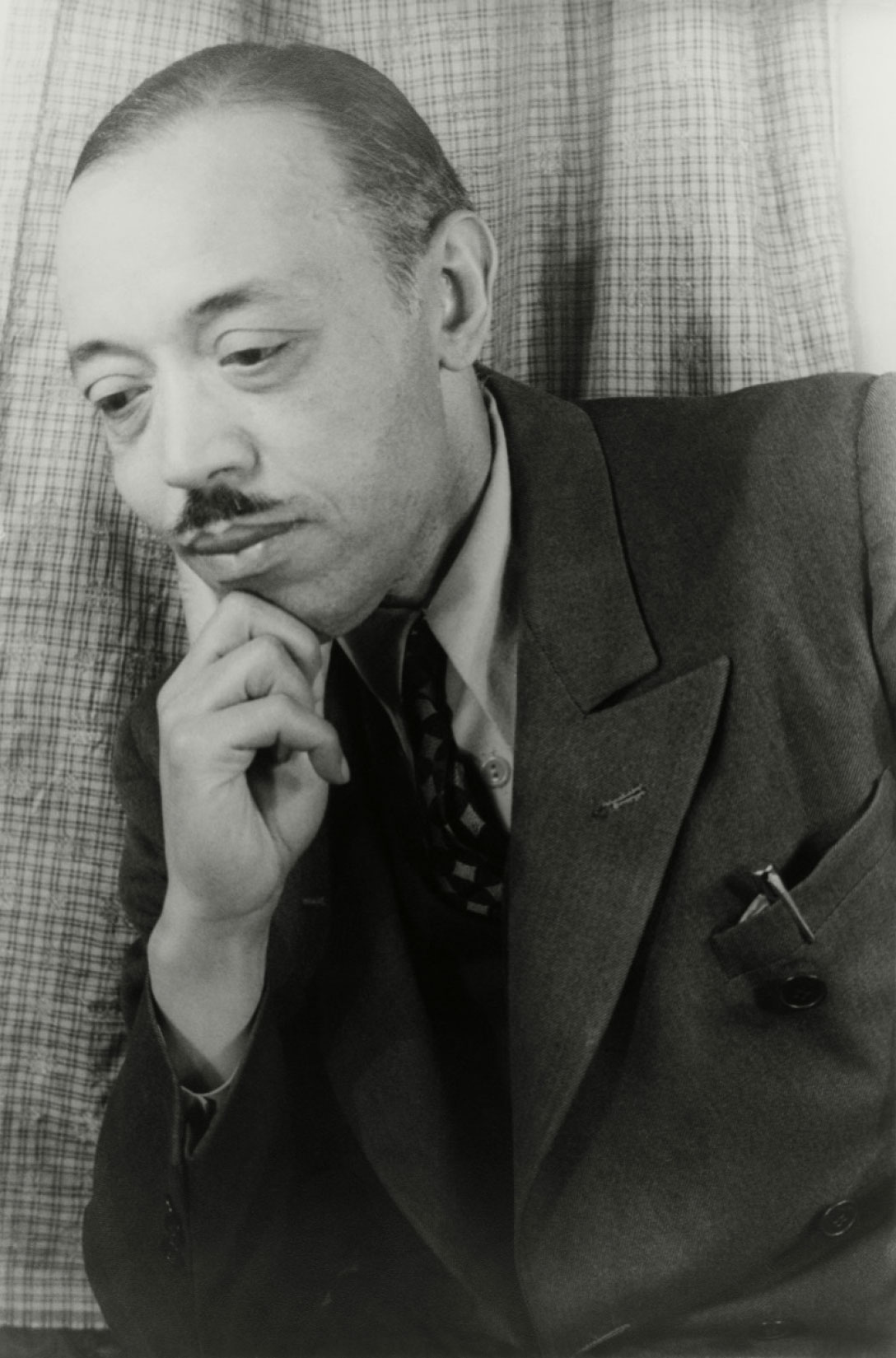

As a national research leader on the works of African American composers, Horace Maxile Jr., PhD, is part excavator and part evangelist.

His quest for important — and sometimes forgotten — musical works has led him to sift through church piano benches, dusty archives and private family collections.

Maxile is associate professor of music theory in Baylor’s School of Music. His discoveries compel an evangelistic side, and Maxile shines a light on the important contributions made to classical and concert music by generations of African Americans.

“Many scholars called my work evangelical because I was trying to pound the pavement and get people to listen, or to consider a work, or to, perhaps, think about a piece when teaching a particular concert,” Maxile says.

The long-lasting impact of African Americans in forms such as jazz, gospel or blues has enjoyed a great deal of scholarly attention. That hasn’t always been the case for African Americans in traditional western forms of classical or concert music.

As a college-aged Maxile learned more about African American composers like Ulysses Kay, Florence Price and William Grant Still, he began to recognize a void in the scholarship on their music — a role he has filled.

Prior to joining the Baylor faculty, Maxile served as associate director of research at the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago. There, he advanced the field of scholarly inquiry on the subject through papers, lectures and podcasts as he scoured the country, from archives to churches, in search of composers and pieces who deserved a broader audience.

Maxile’s method involves an analysis of the pieces he discovers, with an in-depth look at the notes, emblems, forms and scales that comprise the piece, biographical information about the composer and the historical context surrounding the piece. He synthesizes the information into articles and writings. Frequently cited in current scholarship in such forms as journals, dissertations and books. Maxile is a leader in pieces that advance understanding and recognition of the work and expand readers’ and listeners’ understanding of the scope of African American music.

“The thing that I’ve learned the most is to not try to put a composer in a vacuum and believe that he or she should sound a certain way in order to be considered an African American composer,” Maxile says. “There’s a wide array of ways that composers chose to express themselves and not be part of a perceived monolithic expressive voice.”

Today, more than classical music lovers and Maxile’s contemporary scholars benefit from his research. Baylor students do, as well.

Maxile came to Baylor in 2012, spurred by a desire to return to teaching. He also wanted to teach at a Christian university where, he says, “when you talk about the ‘Hallelujah’ chorus, you can get into the ‘hallelujah’ as much as the chorus.’”

In his classes, Maxile is able to use examples discovered in his research that provide some of the real-life examples of the theory he teaches.

“Teaching and research definitely inform one another,” Maxile says. “I can play an example at the beginning of class to pique the interest of my students. That opens the field for discussion. From there, a student might say, ‘Can you tell me a little more about that composer? Where might I be able to find that composer’s works?’

“If I can get people to at least consider the works, give them a shot and put them on the same program with Beethoven, Mozart or Brahms and let the works stand on their own, then I think my work is done.”