Basketball Brotherhood

NBA veterans share story of friendship, call for unity

The phone rang. Inside his Baylor Quadrangle apartment, 18-year-old Melvin Hunt wasn’t expecting a call so early. It was Wednesday, Nov. 30, 1988, the day after the sophomore guard from Tallulah, Louisiana, played in the first-ever men’s NCAA basketball game in the gleaming new Ferrell Center. The voice on the other end was grim. Someone had to tell Dennis.

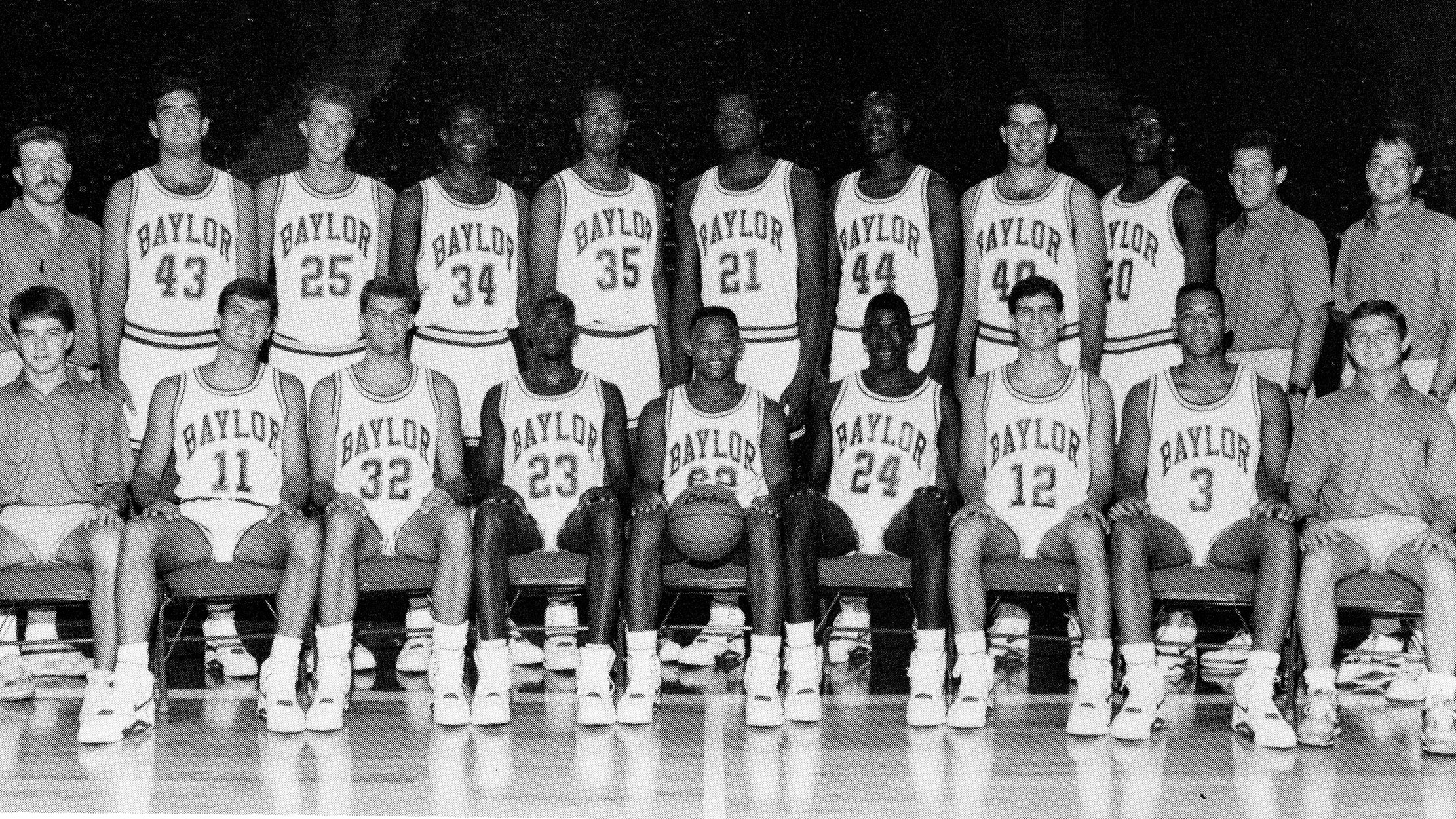

Former Bears: Assists Lead to Success

On March 11, 2019, at Salt Lake City’s Vivint Smart Home Arena, a fan near courtside made a racist insult to Russell Westbrook, one of the NBA’s biggest stars. The fan was permanently banned from the facility, and the league fined Westbrook $25,000 for responding with “profanity and threatening language.” Utah Jazz general manager Dennis Lindsey, BSEd ’92, decided to speak up. It was time to share his story publicly — to deliver a message of unity.

In talks with players, and in Jeff Zillgitt’s March 14 USA Today feature, Lindsey, who has worked in the NBA since 1996, made it clear to his players and to the world that this type of behavior was unacceptable.

“I was so upset about what happened to Westbrook, and it bothered me how [Jazz players] Donovan Mitchell felt and Ekpe Udoh felt and Royce O’Neale felt [the last two are former Baylor Bears],” says Lindsey, who recently was promoted to executive vice president of basketball operations. “They needed to understand that the Jazz organization had their backs and this was a story that was apropos, given the circumstances. I probably should have gone there a long time ago.”

In USA Today, the Clute, Texas, native and runner-up in the voting for the 2018 NBA Executive of the Year, discussed how sharing a roof and life with people from diverse backgrounds shaped his perspective on race and equality. Taking a cue from San Antonio Spurs coach Greg Popovich, Lindsey talked about “our national sin” of racism and how it’s time for Caucasians to take stock of ourselves and “just listen for a second.”

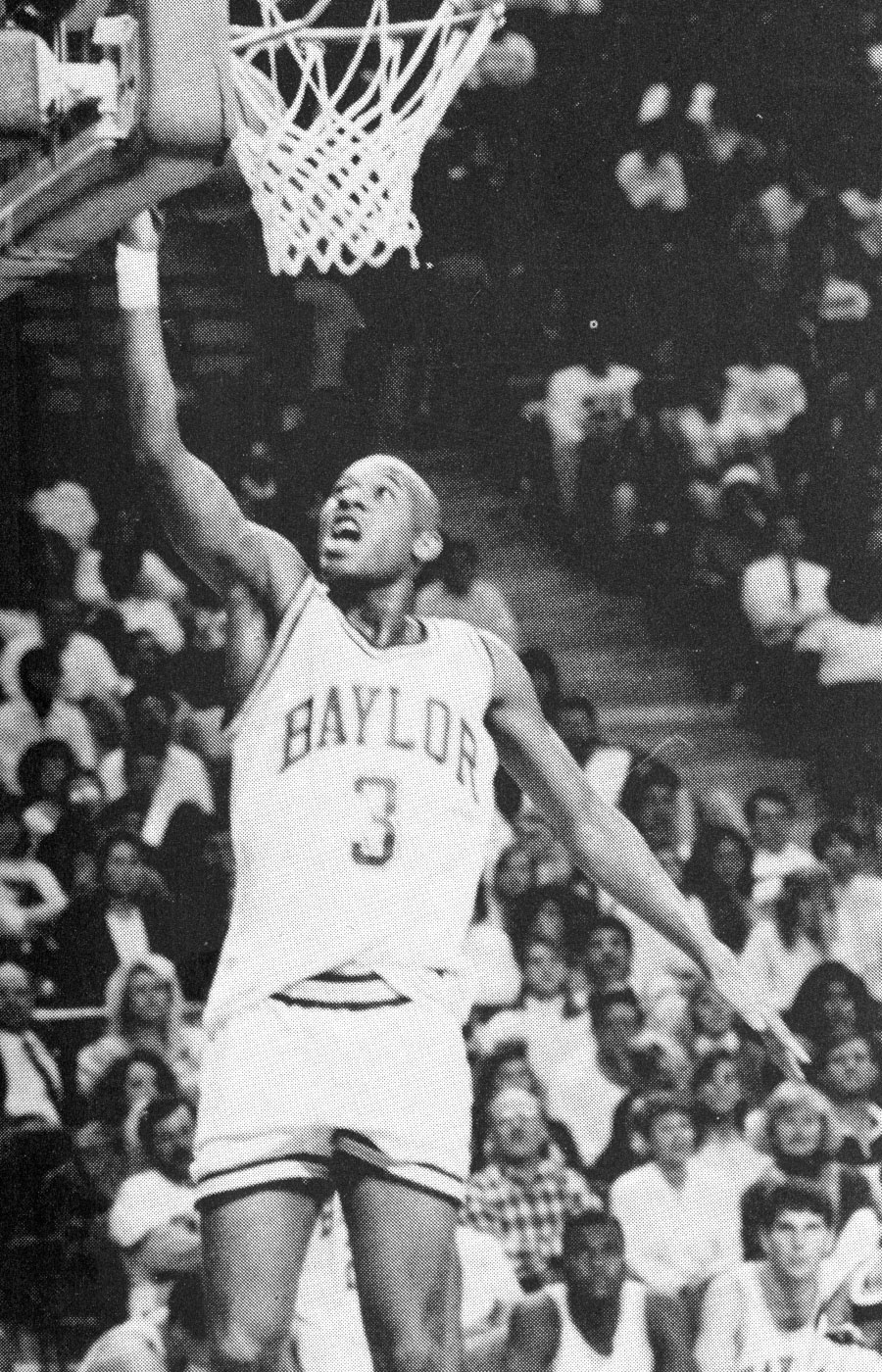

“You see a white guy in Utah, there’s some almost automatic assumptions people make. Oh, well, he’s surely, he’s this, this and this,” says Melvin Hunt, BBA ’91, MSEd ’95, Lindsey’s longtime friend and former NBA colleague, Baylor teammate and roommate. Hunt is lead assistant coach of the Atlanta Hawks. “And then you realize, no, he’s not. Dennis is not that at all. He’s quite opposite of those things, quite different. He was raised in a home with a dozen disadvantaged kids: black and white, Asian American and Hispanic, a little bit of everything.

“I was really proud of Dennis for having the courage to speak out because a lot of people, we don’t want to speak about racism,” Hunt says. “As soon as you start talking, there is a large segment that you’re going to turn off. For Dennis to have the courage to step out and to speak about it, when he did and how he did it, I thought it was very appropriate. It was the right thing to do and just shows who he is as a man.

“That’s one reason he’s such a good general manager. He’s good with people,” Hunt continues. “A lot of that was started at home and was nurtured as we went on to college. And as we went through our time at Baylor, it just grew and grew and grew.”

Hunt knows firsthand, as the two have been friends for more than three decades. They spent five years together with the Houston Rockets from 1999-2004. With 20 years in the NBA coaching and scouting, Hunt also has experienced success at basketball’s highest level, in part due to his efforts to see past

the surface.

“I’m not going to lie and say I don’t see color. Of course I do — I’m not blind,” says Hunt. “But having people from different cultures and backgrounds just means we have some variety, which may bring some different ideas and beliefs to the table. I welcome and enjoy that. I love the melting pot.”

Hunt — who has spent ample time with international players — describes Lithuanians Zydrunas Ilgauskas and Jusuf Nurkic as “like sons.” His wife Carmen likes to tell him that he has more 7-foot foreign-born sons than anybody in America.

“I get asked, ‘How do you end up connecting?’ Because they’re people. We’re all just people,” Hunt says.

A Fast Friendship

Hunt and Lindsey met on a recruiting visit to Baylor in 1986. They related through their love of basketball, sneaking off to find places to play on campus.

“From the first day we met, Dennis and I hit it off,’ Hunt says. “We instantly bonded through basketball, just loving to hoop. Dennis and I didn’t really have anything to offer except conversation and friendship, so it made things really pure. There were no agendas.”

“Melvin’s family is amazing. He just comes from good people,” Lindsey says. “We both grew up in good families, modest upbringings that produced competitive guys. Melvin and myself kind of had a PHD background. It’s what some in professional football call poor, hungry, and driven.”

After the visit, Melvin and Dennis held weekly calls on their home landlines: Saturdays at 10 a.m.

“We made our college decision together over the phone. It was pretty cool,” Hunt recalls.

Freshman year

“When we got to Baylor, there were three white freshmen and me joining the team,” Hunt says. “When you get young men in from all over the country, you just never know what players’ backgrounds are like.”

Without each other knowing, Dennis and Melvin both went to the coaches to request the other as a roommate.

“The coaches were really relieved, because they didn’t have to put us with upperclassmen or try to find other arrangements. It worked out seamlessly,” Hunt says. “It was a great rooming situation. We respected each other and we learned a lot about each other’s upbringing.”

Hunt laughs about his youthful, stereotypical concern that Lindsey, a Texan, might only want to listen to country music at their apartment. Early on, when Lindsey sparked a discussion about the music of Prince, Hunt’s fears were put to rest.

“We discovered our shared love for music, and then we started seeing so many similarities.”

“We discovered our shared love for music, and then we started seeing so many similarities,” Hunt says. I didn’t have a car my freshman year, and Dennis — I call him D Dale, which is what his folks called him — I don’t know if they ever knew, but D Dale would always hook me up if I needed the car. We were typical roommates, always covering for each other in those freshman classes, getting in trouble for being four minutes late to Coach Iba’s practices. We shared everything.

“And it’s funny — color, our skin color was so, so, secondary and down so far down the line, it was crazy. Dennis and I would just hang together with friends and do stuff. It was a whole lot of fun. We had a blast at Baylor.”

Under Coach Gene Iba, the freshmen roommates experienced the thrill of making the 1988 NCAA tournament, the Bears’ first trip there in 38 years. The team was led by the Southwest Conference’s leading scorers in seniors Darryl Middleton and Micheal Williams.

Although Dennis and Melvin wanted to continue being roommates during their sophomore year, they split up to each help guide a pair of freshmen teammates.

“Two of the new guys were black and two were white. We ended up doing what was best for the team since the coaches decided Dennis and I were trustworthy,” Melvin says. Dennis moved a few doors down, still within “The Quad.”

The duo looked forward to next season, when the team would move home games from the Heart of Texas Coliseum to a sparkling new on-campus arena.

The Call

On Nov. 29, 1988, Hunt, Lindsey and the Bears hosted the Ferrell Center’s first-ever NCAA men’s basketball game. San Diego State won 83-58.

Driving home to Brazoria County in the wee hours after watching Dennis play, the rest of the Lindsey family — father Dennis Earl, mother Carol, Dennis’ sister Christy and a foster child — headed south. On State Highway 36, near Caldwell, the Lindseys’ vehicle was struck by a drunk driver. Dennis Earl and Christy were injured. Carol, only 37 years old, was killed.

Someone had to tell Dennis.

Still — 31 years later, Melvin Hunt remembers that fateful day:

“I was still in mine and Dennis’ old apartment and that’s where, when Dennis’ mom passed after the game, from the car accident, that’s where [Dennis’ aunt] called me. It was probably the most difficult thing I’d ever done in my life. At age 18, it was the most difficult thing I’d ever experienced. I am shook.

“I don’t know what to say, don’t know what to do, but I am rocked. And I put my clothes on, and then I take them off. I said, ‘Well I’m not going over there.’ Then, I put my clothes back on. And I thought, ‘I got to go over there. So let me go. Let me just step up and go over there.’ And then I took off my clothes again. I know I took my clothes and shoes off and on at least three times.

“And I just sat down and I called him. I wanted to see if Dennis was awake. Sure enough, he was. He wasn’t groggy. That just showed how God has you ready for whatever it is that you ask for — you’ll be prepared.

“And I said, ‘Hey, what’s up man?’ just casually. I said, ‘Well, I need to come by and talk to you.’ His place was a hundred feet away.

“I walked over there — he left the door open, unlocked and a little ajar. I walked in, and I don’t even remember how I did it, but I told him. And at that moment, I had to stay there, because I didn’t know what effect it was going to have on him. And so, I’m nervous about that. I’m standing next to him. Then he’s taking a shower — I’m standing outside the door.

“I don’t know what to do, what to say. But I knew to stay there with my friend. And I’m just really thankful that God chose me to be the one to be there with him.”

With great emotion, Lindsey described the moment to USA Today, “It wasn’t a black man from Tallulah, Louisiana, telling a Caucasian man from Clute, Texas, that his mom had just passed. It was just two people hugging, embracing, crying, and I’ve thanked him a thousand times privately.”

“Because of the time we spent together and the experiences we shared, we’ll always have a special bond.”

“It was just a tough go of it — he also had gotten hurt,” Hunt says of Dennis, who took a red shirt that season and returned home to help his father and sister recover. “Our coaches tried to help us as much as they could. In Dennis fashion — he is a tough guy — he worked himself through it. The way his folks poured into him, the way they emphasized and de-emphasized certain things in his life, that really helped him get through it. Because of the time we spent together and the experiences we shared, we’ll always have a special bond.”

Atypical upbringing

In 1970s and ’80s Brazoria County, Texas, an hour south of Houston, the Lindseys practiced loving their neighbor so deeply that preaching it wasn’t really necessary. On and off through Dennis’s youth, his parents — his father a Vietnam vet turned Dow Chemical pipefitter, and his saint of a mother — served as house parents to numerous disadvantaged children at the Brazoria County Youth Home in Freeport, in addition to being foster parents for many others.

Dennis lived in the youth home during three periods: as a young child, during second through fourth grade, and again from his sophomore through senior years at Brazoswood High. He shared the home and his parents’ love and attention with as many as a dozen youth of varying ethnicities at a time.

“As you can imagine, there were times I just wanted it to be me and my parents and my sister, and I wanted their undivided attention instead of having it divided a dozen ways amongst the kids. But deep down, I knew it was the right thing,” says Dennis, who maintains relationships with some of the former youth home kids to this day. “When you live with somebody, work with somebody, compete with somebody, you know their heart.”

Similarly, Lindsey told USA Today, “…when you live with someone in closer quarters, you realize there’s one race — the human race. That’s what we need to be talking about. That’s our national discussion and we just need to admit where it’s at and where our hearts are. A lot of it is fear and ignorance.”

Many factors came into play with the timing of Dennis’ telling of his very personal story. In the past, he has had conversations about race relations and others about his mother and how drunk driving devastated his family. However, he had never been able to verbally relate the two until the Westbrook incident brought everything to the surface at once.

“It was always too raw,” he explains, “but this was a time when I thought everybody would understand the example that I’m trying to give them where, truly, there are just situations where nothing else matters other than trying to be a good human being.

“I felt like it’s been a little bit of a personal calling. The tenor of our political environment had a little bit to do with it,” Lindsey continues. “Not speaking up would feel disingenuous considering how I was raised in the youth home in those three stints. Sharing the message that there’s really only one race is being true to the youth home, to my family, and to [fellow house parents] the McReynolds and the Gibsons, who are literally my deceased parents’ lifelong best friends.”

The Remaining Baylor Years

In subsequent years, Hunt, Lindsey and the Bears alternated between struggles and success: a highlight was a trip to the NIT Tournament in 1990 with new teammates such as Julius Denton, Kelvin Chalmers and David Wesley. The relationships and shared experiences still resonate deeply with Lindsey.

“A college basketball team spends so much time together,” he says. “Melvin and I, while we were good guys, we weren’t perfect. We have stories that we all laugh about, like our trip to Tokyo — a San Diego trip when we performed a skit of the coaches that we still talk about. You get things that are common bonds: the struggle of the work, the competition for playing time, victories, embarrassing defeats, the people. Coach Iba, Danny Kaspar, who’s now the head coach at Texas State, was the lead assistant and recruited Melvin, David Wesley and me. Tim Schumacher [another guard on the team] is also one of my closest friends.”

The Next Generation, Renewed Baylor Ties

Melvin and Dennis have seemingly unending commonalities stemming from Baylor, where both met their future wives, Carmen Greer Hunt, BSEd ’94, and Becky Dry Lindsey, BSEd ’89.

“The DNA that we have that kind of attracts us to Baylor, and the common connections have been really cool over the years,” says Dennis whose father-in-law F.A. Dry coached Baylor football and niece Alyssa Dry played Lady Bears basketball.

Another chapter in the Hunt and Lindsey story has been written by their eldest children.

“It was a little surreal going back to games at the Ferrell Center. I knew that Jake coming to Baylor would restart some connections that we had and then make some new ones, but it’s been like an exponential accelerant,” Lindsey says, mentioning his former trainer David Chandler, Mark Buchanan, Joey Fatta, Nelson Haggerty and Scott Drew.

Dennis and his son Jake Lindsey, BBA ’18 — a beloved member of Baylor’s basketball team that went to two NCAA Tournaments and one NIT — are believed to be the only father-son duo to play Baylor basketball. Although Jake’s career was cut short by injuries, he penned a touching piece about his Baylor experience in March for Champions Tribune on baylorbears.com. He graduated cum laude with a business finance degree, and he married Tiger Maddox, BA ’19, in September.

“I didn’t understand the impact having a second-generation Lindsey that has rolled through Baylor would have on us. For my wife and me, it’s made our gratitude for the Baylor Family all that much deeper,” Lindsey says.

Braya Hunt, a senior setter/defensive specialist on Baylor’s volleyball team, has twice been named Academic All-Big 12 (first team). Last November, she also wrote for the Champions Tribune about her efforts to spread the love of Christ through missions.

“It’s been the coolest thing to watch Jake out there as a leader playing basketball at Baylor, wearing my jersey number,” says Melvin, who years ago unexpectedly spotted a young Jake at a Nike All America camp. “Even then, Jake was making all the right plays and being a team leader like I tried to be. I really connected with Jake and valued his role with Baylor. I loved to hear the announcers speak to how Jake was kind of the glue for the team.”

When Jake began his junior year, Braya enrolled as a Baylor freshman.

“The first thing that I said to Jake when Braya decided to go to Baylor is, ‘Take care of her. Be her friend. Watch out for her.’ I think he did,” Dennis says. “He told me he wasn’t surprised that Braya’s a really smart, sweet person.

“I joke that my two majors at Baylor were path of least resistance and academic survival, but Jake was a true student-athlete,” Dennis says. “I am very proud that he was able to come through Baylor with a rigorous course load, and be at the top of his class. He’ll have a lot of options because of that. And with Jake having been [fellow basketball player] King McClure’s roommate, we both experienced reaching across racial barriers in meaningful ways at Baylor.”

Dennis says these past few years have been a blessing: lasting memories include the Jazz hosting a Baylor/Gonzaga scrimmage Jake’s freshman year, the Bears’ first-ever No. 1 ranking and run to the Sweet 16 Jake’s sophomore year, and Baylor playing in the Salt Lake region during the NCAA Tournament this past March, when Dennis caught up with several friends and former teammates.

“When Baylor was playing in Utah, Dennis was pumped,” Melvin laughs. “He tried to get me to fly out there, and I reminded him, ‘Dennis, we’re playing the Jazz in Atlanta that night. I will be busy coaching. The irony of that was pretty funny.

“It started with Dennis and me, and then it goes to another generation with our kids — just amazing. And have it all happen at Baylor is like the icing on the cake. [The ‘Waco’ Lindseys: Claude, Becky, Ryan, Jennifer, and Will] are like family to us. They looked out for Dennis and me, and then they did the same for Jake and Braya,” Melvin says. “It really speaks to Baylor, speaks to the Baylor family, how we take care of each other.”

That caring has extended into the NBA. Former Rockets Carroll Dawson, BS ’60, brought Dennis to the NBA in 1996. Then Dawson and Lindsey helped Melvin to his first NBA job in 1999. They also traded for former Baylor teammate David Wesley in 2004. Melvin later brought David to the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2006, when they shared a run to the NBA Finals as coach and player. (Read more about these connections at baylor.edu/magazine.)

Lifelong friendship

“All this goes right back to what Baylor has been about for me and my family. It’s real family,” Hunt says. “It’s so cool, with Dave and Dennis and me all being a part of the NBA, from the same Baylor team. It’s pretty special,” reflects Hunt. “And the bonds just go deep. I could fill up a notebook or two with all that we’ve been through. It’s just the beauty of our relationship.

“I can’t say it enough about how so many of these values and these stories are just born out of being at Baylor,” he continues. “No disrespect, but I don’t think they would be the same stories had I been at Texas A&M, Sam Houston State or wherever else it could have been. Our university is such a unique place, that a lot of things that we were able to grow in and grow through, were specific to Baylor.”

Lindsey concurs.

“We all have people in our lives just become special to us. Those common bonds of having great parents, to basketball, to now Baylor and our kids, to me helping Melvin get his first NBA job, the accident itself. Those common ties of victories, of tragedy, of defeats, it brings you together. We care about each other’s families — ours is a relationship that will be lifelong, certainly.”

Full Circle

Baylor, basketball, empathy, understanding — these things brought Melvin and Dennis together.

“Sometimes you’re in the majority, and sometimes you need to understand what it’s like to be in the minority. We’ve all been there.”

“The youth home gave me a unique upbringing that was, in hindsight, a complete gift, especially with what I decided to do with the rest of my life and career and family,” Dennis says. “It was very important that my kids be exposed to multicultural backgrounds.

“Sometimes you’re in the majority, and sometimes you need to understand what it’s like to be in the minority. We’ve all been there,” he continues. “I’ve been subjected to things and I’ve had friends in the minority be subjected to things that I’ve witnessed up close. For example, when Melvin drove home from Baylor to Louisiana, there were towns that he would go out of his way to avoid. If he had to go through, he would not stop and get a pop or get gas. Other guys on the team would say, ‘Hey, don’t stop here.’ Being 18 to 23, and given my background, that really bothered me.

“Now I have a platform to go on a radio show or do an interview and say, stop. Let’s just stop and listen and empathize. Take a few moments to think about what it would be like to be in someone else’s shoes.”

Dennis had to tell someone.

Perhaps one person can never fully understand the perspectives or circumstances of another; but Melvin Hunt and Dennis Lindsey are living proof that looking past the surface can become a lifestyle, that our similarities often far outweigh our differences, that empathy brings healing, that we all should really try.