Anthropology of Health

Baylor's historically strong anthropology department looks to the future with a focus on health.

With big changes afoot and a doctoral program in the proposal stages, Baylor’s Department of Anthropology is bolstering its historical strengths, recruiting top talent and preparing for a future focused on health.

In September 2015, Michael Muehlenbein, PhD, received an unexpected phone call from former classmate Katie Binetti, PhD, senior lecturer of anthropology at Baylor.

“I’d read some of his published work, and I knew that he had established himself at the forefront of biological anthropology, which is sort of a confluence of human health and anthropology and a focus we wanted to emphasize departmentally at Baylor,” Binetti says.

Binetti, who keeps an eye on the relatively small field of anthropology within academia, knew of Muehlenbein’s move to the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) when she made the call in 2015. The two overlapped by a few years as graduate students at Yale University.

As early as 2014, Baylor anthropology faculty began discussing a new direction — or guiding emphasis for the department — and the possible creation of a doctoral program. In the years that followed, a number of factors continued to motivate these discussions, including trends in anthropology, public health and medicine, as well as the potential for increased interdisciplinary research activity. Lee Nordt, PhD, dean of Baylor’s College of Arts and Sciences, advised the department to seek the counsel of a few outsiders in the know.

Lori Baker, PhD, Baylor vice provost for strategic initiatives, collaboration and leadership development, says the department identified three leaders within the field and invited them to campus. Baker, BA ’93, MA ’94, also is an associate professor of anthropology.

“We wanted those leaders to give a lecture here and tell us how they would build out a department to support a new graduate program focused on human health,” Baker says. “If things went well, we were hoping to recruit one of these people to Baylor to be our chair.”

“We have to maintain excellence in topics like archaeology and forensic science and things that we do well; and, we need to expand our health offerings to accommodate our undergraduate students.”Michael Muehlenbein

Both Muehlenbein’s lecture in November 2015 and his recommendations addressing the future of undergraduate education and the envisioned graduate program, resonated with anthropology faculty and Nordt. In January 2017, Muehlenbein was invited back to campus to formally interview for the chair post.

“His vision was spectacular,” Baker says. “His personality is perfect, too. He’s a ‘doer.’ He knows what needs to be done and he pushes forward. We weren’t sure we could get him. When we asked him to join us, and he said yes, we were blown away.”

Collaborative Future

Before accepting the position, Muehlenbein recognized Baylor’s historical strengths in archaeology, forensic anthropology and applied anthropology, as reflected in the expertise of department faculty and also in the extraordinary field opportunities available to undergraduates. He wanted to capitalize on these intra-departmental strengths without replicating them. Similarly, he wanted to draw on the expertise and course offerings within other departments in building the anthropology graduate program and multiple new undergraduate minors.

“I met individually with 13 different programs across campus because I wanted to see what classes might be appropriate for our graduate students,” Muehlenbein says. “To be clear, I have no interest in farming out our responsibilities to other departments, but I’m not going to reinvent the wheel.

Among the examples he cited, Muehlenbein notes the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders in Baylor’s Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences already offers a great class in health communication.

“Or, take project management: Our [Hankamer] business school already does that well. For a course in program evaluation, we turn to the [Diana R. Garland] School of Social Work,” he says.

Roughly 75 such courses were identified and categorized to assist students in customizing a program.

“But within a specified range of variation,” Muehlenbein says. “We want them trained largely in skills rather than theory. They need marketable skills.”

He also spearheaded physical renovations to the department that showcase the work anthropology faculty are doing and underscore the relevance and versatility of an anthropology undergraduate degree. A physical space for collaborative, interdisciplinary research is also included in the anthropology core lab.

“Most high school students aren’t exposed to anthropology,” Muehlenbein says. “Or what they know — or think they know — about anthropology is based on CSI or Indiana Jones or Jane Goodall.”

Located on the third floor of Marrs McLean Science Building, two commissioned murals provide a colorful proscenium as visitors enter the newly renovated space. Artist Callie A. Gabbert skillfully replicated sections of well-known cave murals that were discovered in two separate locations in southern France. The originals date back to 17,000 B.C. and 30,000 B.C.

Six large, glass cases contain information and artifacts that highlight the diversity of anthropology and the relationship between anthropology and museums. Mayborn Museum Complex Village Manager Trey Crumpton III, BS ’05, MS ’11, and museum studies graduate candidate Krista Barnum assisted Muehlenbein in the development of the cases.

The displays serve to provide a richer understanding of the anthropology field, stoking the imagination for students and visitors to the department.

Baker says the displays benefit faculty, too.

“It’s certainly helpful when we have high school students on campus looking at the department, but it also lifts morale internally,” she says. “Each of us sees what the other faculty are doing, and the display cases are something to be proud of.”

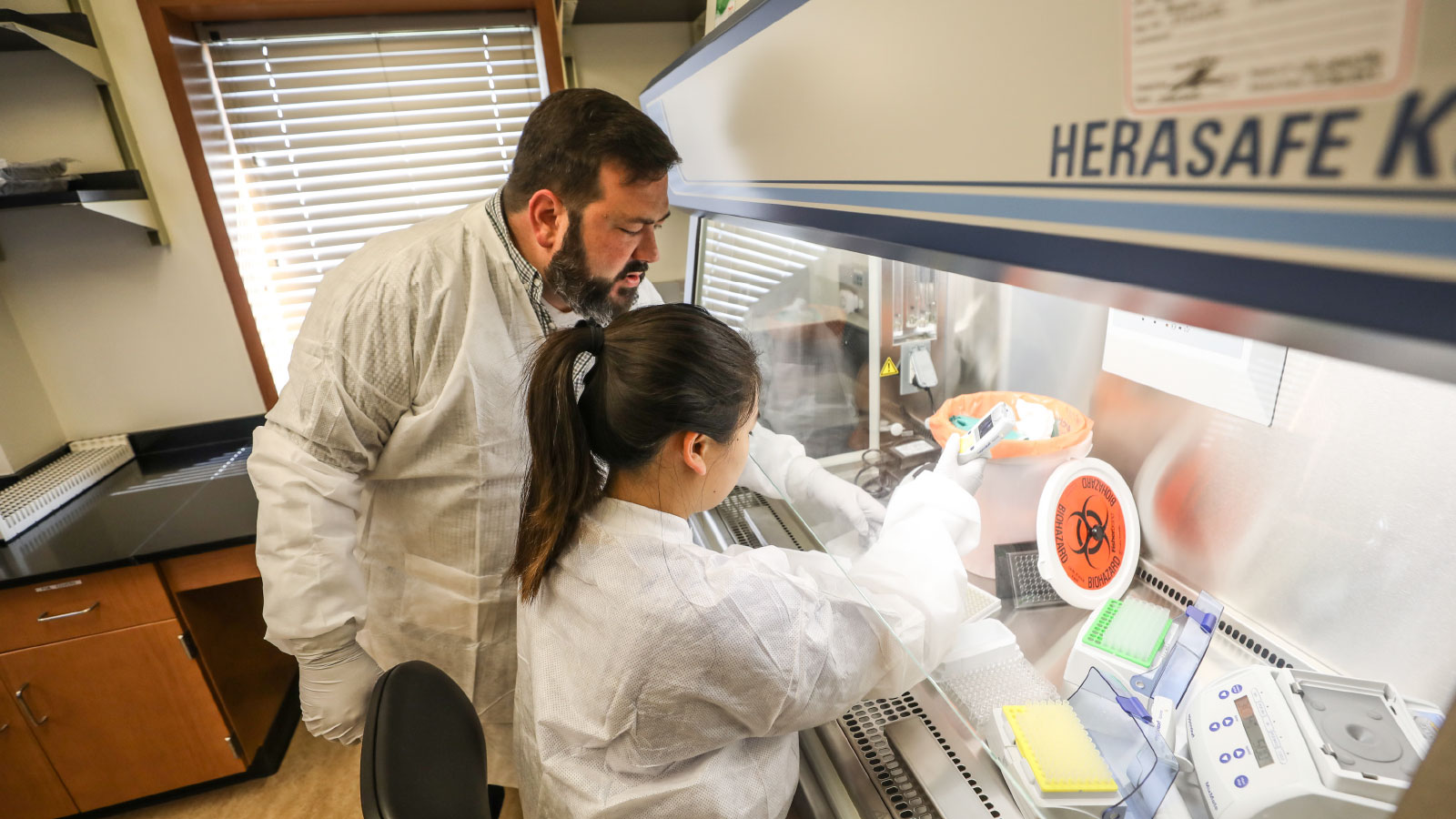

Baker and others particularly look forward to a soon-to-be-opened newly outfitted anthropology core lab, providing the space to share ideas and pursue research with one another and with researchers from all areas

of campus.

“[Muehlenbein] has invested heavily in the anthropology core lab, which is inspired by a medical school or National Institutes of Health type model,” Baker says. “The idea being that if you put people together, there’s going to be some synergy, some new ideas generated; we’re supporting one another, but also offering advice, suggestions, et cetera. All the equipment is purchased, and we’re looking forward to using that space actively in the summer and fall.”

In addition to the doctoral program proposal now under consideration, the anthropology department is developing a master’s degree jointly with the museum studies department, and undergraduate minors in global health, human biology, and archaeology.

“We look forward to offering these things in collaboration with other departments,” Muehlenbein says. “It’s expanding anthropology in all directions.”

Emphasizing Health

Central to his vision, Muehlenbein saw something special in the success and popularity of Baylor’s undergraduate pre-health studies programming and the prevalence of the Baylor name within healthcare throughout the state and beyond.

“I saw opportunities to refocus the anthropology department more toward health in general,” he says. “I don’t want to call what we’re doing ‘medical anthropology’ or ‘biomedical anthropology’ because those labels actually mean something very specific to anthropologists. Within the context of a graduate program, I mean to emphasize more of a holistic understanding of health, using tools — both qualitative and quantitative — within anthropology.”

While the breadth of Muehlenbein’s training and research interests resist the sort of tidy description one might feature at the top of a professional résumé, his career to date exemplifies the interdisciplinary nature of anthropology and its critical place in the future of health-related research. His ongoing work explores evolutionary endocrinology and ecological immunology (or how and why immunity has transformed and diversified over time). He also has projects focused on global health, including emerging infectious diseases, conservation medicine and disease transmission between humans and other animals.

In 2018, the department recruited biocultural anthropologist Mark Flinn from the University of Missouri, where he served as chair of the anthropology department for nine years. Flinn’s research, broadly speaking, aims to understand how and why social relationships influence child health. Adding such faculty with research within that nexus of anthropology and human health, Muehlenbein says, will position faculty and future graduate students to receive top federal and private grant funding, an important metric as the University continues to seek R1 classification.

“As we plan for the future and think about where we want to place our PhD graduates, we want to develop a program that will equip them with skills that are marketable outside of the Academy,” Muehlenbein says.

Muehlenbein notes anthropology professors have historically trained doctoral students to become faculty members. But that model is broken, given a saturated academic job market.

“We don’t want solely to train future professors,” he says. “When we launch a PhD in anthropology with specialization in the anthropology of health, we want to make sure our graduates have a diversity of experiences and skills that could qualify them for jobs in any number of sectors. This means project-based courses that focus on applied methods as well as other unique aspects of our program, like a required internship at

a local agency such as the Waco Family Health Center.”

Anthropologists are highly valued, dependent upon the skills they bring to the table — being able to combine qualitative and quantitative methods, being able to understand the interplay between biology and culture, and interpreting how to develop and manage all sorts of international projects.

“Anthropologists work in government, for NGOs, in the military, in business and entertainment,” Muehlenbein says. “You find anthropologists everywhere.”

Serving Undergraduates

While the prospect of a new graduate program is exciting, Muehlenbein says he is not interested in launching such a program at the expense of what Baylor currently offers undergraduate students.

“This is important to me,” he says. “We have to maintain excellence in topics like archaeology and forensic science and things that we do well; and, we need to expand our health offerings to accommodate our undergraduate students.”

Approximately 35 percent of the incoming class will likely be engaged in Baylor’s pre-health programs — that is, via their declared major, minor, emphasis or concentration. Muehlenbein speculates that Baylor students are attracted to the study of human health and the health professions because of “their sense of compassion and service.”

Anthropology as a discipline is well-positioned to broaden and enrich existing pre-health coursework, research and internship experience for pre-health majors. For example, as students study disease transmission and immunology, the tools provided by anthropology allow tomorrow’s health professionals to understand how and why people get sick.

Furthermore, not all first-year students who think they want to become doctors will continue on that path. For example, Muehlenbein was a pre-med major at Northwestern University until he got a taste of research.

Sarah Cruthirds, a senior University Scholars major from Spring, Texas, came to a similar crossroads and sought guidance from Muehlenbein, her senior thesis director.

“I was on the pre-med track my entire time at Baylor, and I do still see myself going to medical school eventually,” Cruthirds says. “But heading into medical school at 22 seemed daunting. It’s a six- to eight-year investment between school and residency.”

Having enjoyed her thesis research on reproductive ecology, Cruthirds decided to press pause on medical school and pursue a Master of Science in epidemiology at Tulane University. She begins her graduate studies in the fall.

“I’ve been working with Dr. Muehlenbein over the last two years, and he’s gotten to know me really well,” she says. “He helped me make the decision about grad school. He’s an excellent professor, and he’s really been a mentor to me. It’s been so valuable to have

his ear.”

Binetti, who serves as undergraduate program coordinator, interacts with freshmen in her classes as well as high school juniors and seniors visiting the Baylor campus with their parents. She says many of these students express a desire to “help people” by becoming doctors.

“I don’t discourage that goal, but I do tell them that other fields like public health, where you find a lot of anthropologists, have the potential to impact millions of people,” Binetti says. “The beauty of anthropology is that you can take the degree in any number of directions.”

Since anthropology means the study of humans, the possibilities for collaboration across disciplines are virtually endless. Binetti says, one could argue that every academic endeavor studies people in some way.

“We do biology, we do geology, we do sociology, psychology, statistics. The goal is to be holistic and understand people from all perspectives.”Katie Binetti

“What makes anthropology unique is that we’re studying people from within and from without. Ours is a holistic view,” she says. “We do biology, we do geology, we do sociology, psychology, statistics. The goal is to be holistic and understand people from all perspectives.”

Field Work

Baylor’s anthropology faculty have led undergraduate students all over the world to participate in archaeological digs, forensic analyses and data gathering. These experiences allow students to apply in real life the skills and concepts learned in the classroom while contributing to ongoing research in a tangible way.

Muehlenbein’s field work specific to monkey and ape health and nature-based or “eco-” tourism has taken him to places such as South Africa, Mexico, Thailand, Malaysian Borneo, Japan, St. Kitts, and the British territory of Gibraltar.

“Since 2004, I’ve led 128 students abroad to seven different countries,” he says. “It’s something I enjoy, and these experiences are tremendously impactful for students.”

In his first summer at Baylor, Muehlenbein started a study abroad program in Thailand that focuses on global health. Cruthirds was among the 10 students who traveled to Thailand in summer 2018 to survey tourists visiting Patara Elephant Farm in Chiang Mai.

“It was a research-based trip; so, in addition to experiencing Thai culture, learning some of the language, and eating a lot of really great food, we were focused on collecting data, surveying tourists about their travel health knowledge, attitudes, and practices,” Cruthirds says. “A lot of the times as undergrads, we utilize other people’s published research and statistical analyses without understanding what kind of ‘grunt work’ went into those results.”

For two weeks, Baylor students approached visitors to the elephant farm with an iPad in hand. Cruthirds says most people were willing to take the 10-minute survey, which was administered in English.

“I was really surprised by the number of people who did not seek medical advice before going on their trip,” she says. “We’re talking about required vaccines or anti-malaria drugs, seeking advice about eating and drinking, or checking with the World Health Organization or Centers for Disease Control about anything at all. Most came out to Thailand without a thought for their own health or the ways in which their health could impact animal populations there.”

CAUSE FOR CELEBRATION

In early May, faculty from anthropology and other departments, staff from the Mayborn Museum Complex and Baylor President Linda A. Livingstone, Ph.D., gathered to unveil the new lab facilities and artifact displays. In a brief address, Muehlenbein thanked numerous supporters and voiced his eagerness to see the proposed graduate program and undergraduate minors to their official launches, better aligning the department in support of Illuminate, the University’s strategic plan, and its wide-reaching health initiative.

“From my perspective,” Baker says, “the sooner we’re able to bring in doctoral students and put them in this beautiful anthropology lab that Baylor has invested in, and have our faculty collaborating with new doctoral students, the closer we will be as a University toward our R1 goal.”