A Remarkable Legacy

Trailblazing math professor transforms generations

Many Baylor alumni look back on their time at Baylor and recall a professor who influenced their lives and set them on a course toward their future. When that professor is also a trailblazer in her field at a moment of tremendous change in our society, the reverberations are far-reaching and profound.

Vivienne Lucille Malone was born Feb. 10, 1932, the only child of Pizarro and Vera Estelle Allen Malone; her family included educators and community leaders. She grew up in Waco and graduated at age 16 from A.J. Moore High School, not far from the Baylor campus.

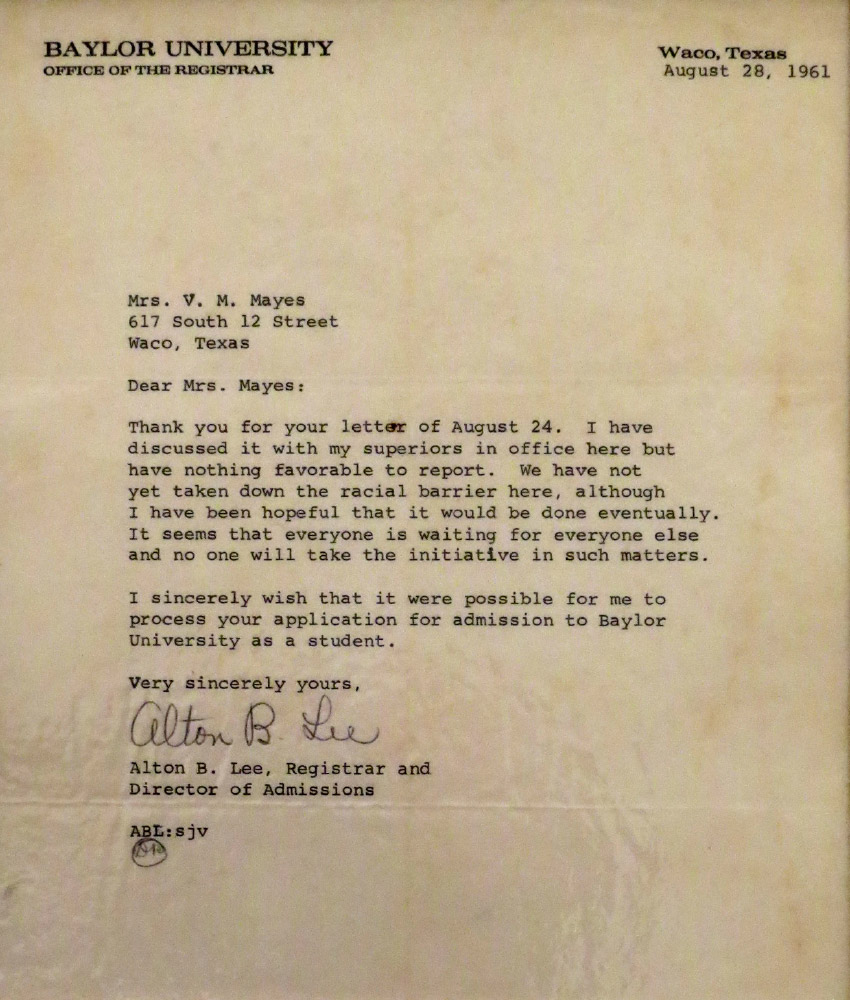

Vivienne Malone-Mayes received this letter after applying to graduate school at Baylor in 1961.

She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mathematics from Nashville’s Fisk University, where she was taught by Dr. Lee Lorch, a prominent desegregationist, and Dr. Evelyn Boyd Granville, the second African-American woman to earn a PhD in mathematics and the creator of computer software to analyze satellite orbits for NASA programs. She married dentist James Mayes during this time and later became the fifth African-American female to earn a mathematics PhD. She credited Granville as the primary reason she pursued the degree.

Malone-Mayes chaired the math departments at Bishop College in Dallas and then Paul Quinn College, which was in Waco at the time. Because she wanted to take more graduate-level classes courses, Malone-Mayes applied to Baylor in 1961, but she was rejected because of her race. (Baylor trustees voted to integrate Nov. 1, 1963.) Malone-Mayes framed her Baylor rejection letter as a reminder of the struggle for academic equality.

Determined to earn her PhD, in 1962, Malone-Mayes enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin, which had been required by federal law to integrate. At the height of the civil rights movement, she participated in and helped lead marches and pickets of restaurants, movie theaters and other businesses in Austin, Waco and elsewhere. Her time as a PhD student was often lonely and stressful. Malone-Mayes persevered to become the second African-American and the first black female to earn a PhD in mathematics from the University of Texas.

Black and Female

At the 1975 Association for Women in Mathematics (AWM) summer meeting in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Malone-Mayes presented Black and Female in which she reviewed her career up to that point. A transcript was printed in a 1975 issue of AWM Newsletter. Malone-Mayes detailed some of her struggles while at the University of Texas that she felt limited her mathematical maturity:

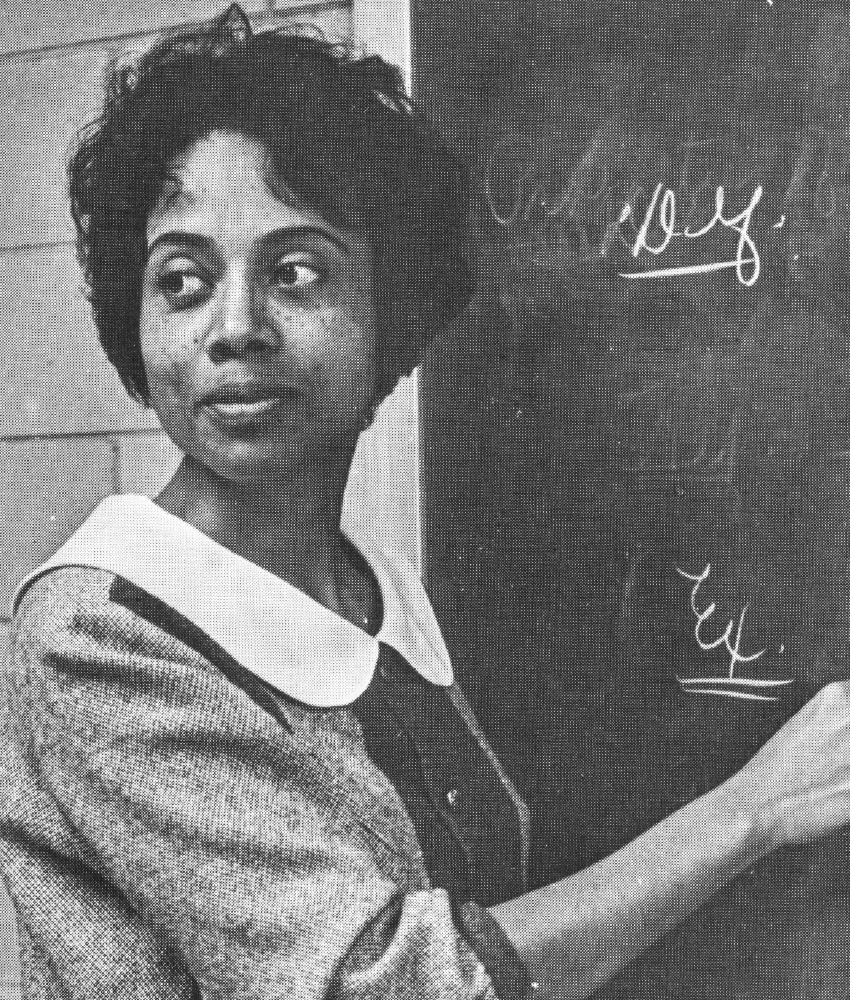

1968 Round Up Yearbook photo

“I could not become a teaching assistant. Why? Black,” she said. “I could not join my advisor and other classmates to discuss mathematics over coffee at Hilsberg’s Café. Why? Because Hilsberg would not serve blacks. Occasionally, I could get snatches of their conversation as they crossed our picket line outside the cafe.”

Malone-Mayes also mentioned in that speech that she was not allowed to enroll in one professor’s class because he refused to teach blacks and believed that the education of women was a waste of tax dollars.

After completing her PhD, Malone-Mayes returned to Waco, and on April 25, 1966, a Baylor press release announced Malone-Mayes’ hiring. By 1971, Baylor Student Congress named her as an Outstanding Faculty Member of the Year.

Malone-Mayes was the first black elected to the AWM executive committee, and she served on the National Association of Mathematicians board. She was a member of the American Mathematical Society, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics and the Mathematical Association of America (MAA), where she was elected director-at-large for the Texas section. Additionally, she was director of the Texas MAA high school lecture program.

Servant Leader

Along with her academic pursuits and lengthy teaching career, Malone-Mayes was a strong servant leader in the community. She was a lifelong member of New Hope Baptist Church, where she was organist and director of the youth choir. Malone-Mayes advocated for Waco ISD students and served on several boards and committees, including Family Counseling and Children Services, Goodwill Industries, and the Heart of Texas Region Mental Health and Mental Retardation Center.

In interviews recorded between 1987 and 1994 by Baylor’s Institute for Oral History, Malone-Mayes recounted what is was like growing up in Waco as a black female. This included her first realization that she was black: when her mother pulled her away from a water fountain reserved for whites. She told of her times on the picket lines and how she preserved the Conner Papers, a large family archive of local African-American history dating back to the 1800s, which she donated

to Baylor’s Texas Collection in 1973.

Malone-Mayes’ audio recordings and written transcripts are digitized and publicly available online through the Institute for Oral History. She also interviewed others for the Institute, and she donated the Vivienne Malone-Mayes Papers to The Texas Collection in 1979.

Malone-Mayes suffered from severe pain and ill health in the final years of her life, forcing her to retire in 1994 after 28 years at Baylor. She passed away June 9, 1995, at age 63. Her death was overshadowed by another prominent Baylor figure who passed away two days later: former University President Abner McCall.

Even in burial, Malone-Mayes faced segregation. Greenwood Cemetery, which contains the graves of many prominent Waco citizens, was divided by a quarter-mile fence separating blacks and whites from 1875 until the fence was finally removed in 2016.

Following Malone-Mayes’ death, her former professor Lee Lorch and fellow pioneer Dr. Etta Falconer wrote: “All her life, to its very end, she was in the struggle to make the path smoother for those who followed. She made her presence in the national mathematics community felt and respected. In the organizations specifically devoted to the problems of minorities and women, there she was, too. With skill, integrity, steadfastness and love she fought racism and sexism her entire life, never yielding to the pressures or problems which beset her path. She leaves a lasting influence.”

Honoring Her Legacy

More than two decades after her death, Malone-Mayes is not forgotten. The Baylor Black Alumni Network gala in November 2017 commemorated the 50-year anniversary of the University’s first black graduates, honored others who achieved firsts on campus, and benefited The Dr. Vivienne Malone-Mayes Scholarship Endowment, which has provided Baylor students with scholarships since 2008. A plaque in her honor is affixed to a memorial lamppost in front of McMullen-Connally Faculty Center. It reads in part, “Scholar, Teacher, Pioneer, Community Member, Loving Friend, Inspiration To Us All—She made the path smoother for those who followed.”

Dr. Vivienne Malone-Mayes is being honored with a 22-inch bronze bust, tentatively scheduled to be installed in late spring inside the Sid Richardson Building near the Baylor Department of Mathematics.

Alex Wheeler, BS ’78, is Malone-Mayes’ son-in-law. He formed a nonprofit entity with intentions of opening a multicultural museum in Waco to educate the public about the contributions of area leaders such as his mother-in-law, A.J. Moore, Paul Quinn and others. Malone-Mayes’ contributions have been recognized in books, including 2017’s Women of Color in STEM: Navigating the Workforce (Information Age Publishing).

Dr. Lance Littlejohn, chair of Baylor’s mathematics department since 2007, says various conversations over the years have led to another appropriate honor of Malone-Mayes’ legacy. Installation of a 22-inch commemorative bust of Malone-Mayes is tentatively scheduled for late April outside the mathematics department offices on the third floor of the Sid Richardson Building.

“Vivienne was a remarkable woman,” Littlejohn says. “She was an excellent mathematics teacher who changed and influenced the lives of many Baylor students. She dealt with rejection and racism throughout her life, but her grace, determination and courage would remain undaunted. I am in awe of all that she accomplished, and the mathematics department at Baylor is proud to remember her legacy.”

Wheeler believes the bust project is an example of momentum he sees at Baylor and in Waco to more fully honor the important contributions of Malone-Mayes and other prominent people of color from the area.

“Being the community-oriented person that Vivienne was, this will have significant meaning not just for Baylor but also for Waco history,” Wheeler says. “What she stood for—and it goes all the way back to her high school days, the connection with A.J. Moore High School right up through teaching at Baylor and Paul Quinn and all of her involvement within the community—all of it is quite valuable from a historical standpoint.”

In 1961, a young lady was denied the chance to become a Baylor student just because of the color of her skin. In 2018, the remarkable woman she became will be honored by her image taking a permanent place on campus, and her story will continue being told.