A Perilous Journey

Combining our Christian mission with "design thinking" principles, Baylor students in this social innovation lab are generating solutions for one of modern history's most critical social challenges.

As a Christian institution with the mission to prepare men and women for worldwide leadership and service, Baylor attracts students who are uncommonly mission-driven and determined to face the most pressing social challenges with compassion and creativity. The University began social innovation labs that cross multiple disciplines to engage and inspire such students to become torchbearers around the globe in dealing with some of the most difficult problems facing society, such as child migration in the Western Hemisphere.

A few of these transdisciplinary social innovation labs first entered the course catalog in fall 2017 and quickly caught the attention of motivated University undergraduates.

Under the purview of the Office of the Provost, Baylor’s Social Innovation Collaborative (BAY-SIC) is a University-wide initiative aimed at recruiting the varied passions and talents among faculty, staff and students in efforts to promote human flourishing in innovative ways.

Dr. Andy Hogue, director of BAY-SIC and the philanthropy and public service program, says a social innovation lab “presents a new model for teaching and learning.” It also brings together faculty and students across disciplines, as well as worldwide partners, with a common objective.

Hogue’s program tackles what he calls, “wicked problems.” These challenges are “so complex that they are irreducible to a particular field or discipline,” Hogue says. “Wicked problems are problems we can’t solve, per se. We believe in bringing to the table the best ideas our disciplines can offer, even as we hold those lightly, knowing that someone else’s disciplinary lens and the experience of those ‘on the ground’ might equip us to better approach the problem. In turn, [this may] begin to move the needle—to offer new ideas about how systems might work better for those most affected by the world’s toughest challenges.”

Understanding Child Migration in the Western Hemisphere

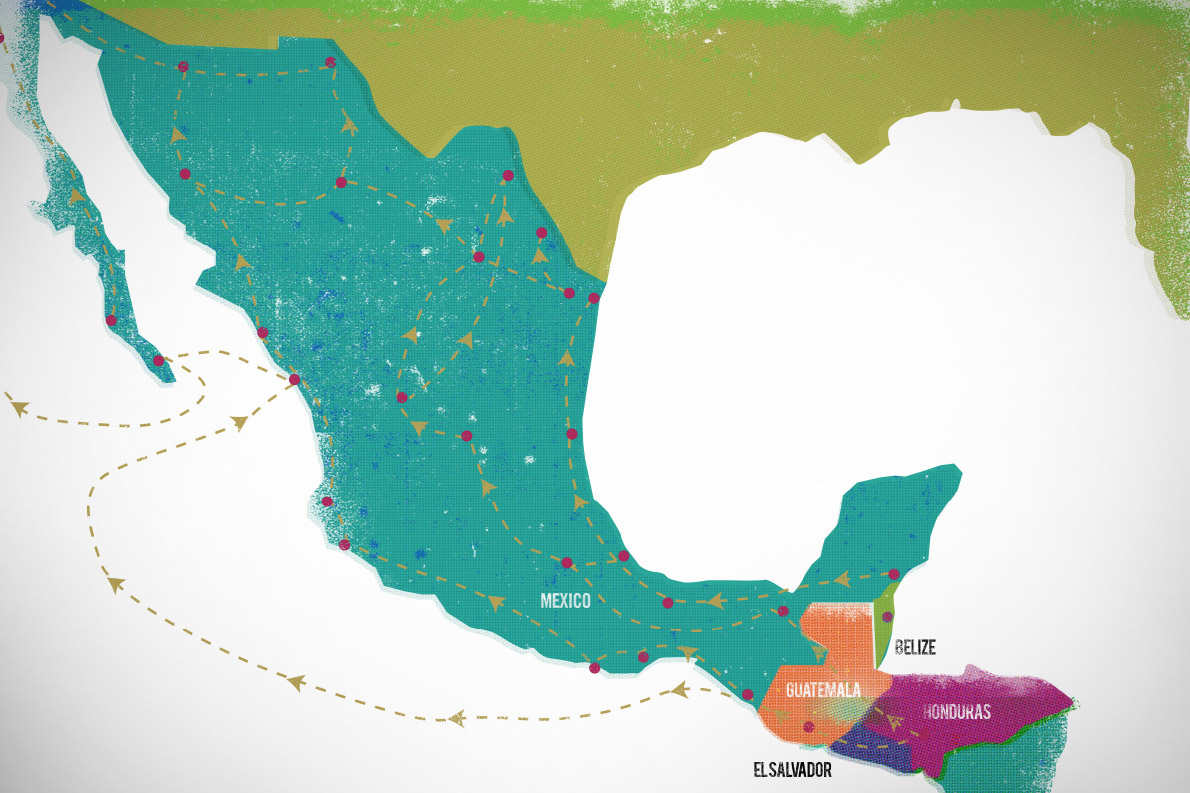

One social innovation lab is working toward tangible solutions to a topic of rapidly increasing relevance. Immigration is top-of-mind for many in the U.S. This particular problem—the flood of unaccompanied minors migrating from Latin America’s “Northern Triangle” (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) to the U.S. border—is vastly more complex than most Americans realize.

In recent years, tens of thousands of minors have endured a perilous journey in hopes of gaining asylum in the United States. It is not uncommon for children as young

as 4 to attempt the 1,400-mile trek from a place like San Pedro Sula, Honduras, a city ravaged by street gangs and booming drug and illegal arms trades. San Pedro Sula’s homicide rate only recently fell from first- to second-highest worldwide.

The journey itself is as dangerous for these minors as the cities, towns and villages they are escaping. Most have to rely on the help of smugglers—criminals who, for a price, will take migrants across various distances in large trucks, shipping containers and the like. In order to cover the longest portion of the journey quickly, avoiding various Mexican immigration checkpoints, minors attempt to board La Bestia (The Beast) or El Tren de la Muerte (the death train), two foreboding monikers for a network of Mexican freight trains that export goods to the north.

“This journey is horrific, and these kids are endangered, threatened and exploited at every stage,” says Dr. Victor Hinojosa, associate professor in Baylor’s Honors Program. Hinojosa is co-leader of the lab with Dr. Lori Baker, associate professor of anthropology and vice provost for strategic initiatives, collaboration and leadership development.

“If they make it through their own home countries, all the way through Mexico to the U.S., all along the way, they’re being victimized,” Hinojosa says. “The smugglers are exploiting these kids, the kids are exploited by criminals of other sorts and by corrupt law enforcement officials. Then, they must find a way to literally jump on La Bestia, riding on top of the freight cars that carry them most of the way through Mexico. Failed attempts result in countless injuries, lots of amputations and deaths—the things you would expect to happen when you jump onto a moving train.”

“This journey is horrific, and these kids are endangered, threatened and exploited at every stage.”

Some may wonder how any parent could choose to send his or her child on such a journey. But, living in a place like San Pedro Sula, parents face these unthinkable choices daily.

“Conditions at home are so extraordinarily difficult,” Hinojosa says. “Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador are now three of the five deadliest countries in the world. They are among the most violent countries in the world where there is not a war going on. Families decide they would rather risk their children’s lives on the journey than see them die at home.”

If unaccompanied minors manage, against all odds, to reach McAllen or Brownsville, Texas, they may have with them nothing more than the phone number of a relative who lives somewhere in the States. Most likely, he or she speaks very little English but must somehow weather the ensuing legal whirlwind in hopes of winning an asylum case.

Hinojosa points to a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees study that found approximately two-thirds of children in detention in the U.S. have probable asylum claims.

“One of the experts we invited to speak with our students [in the lab] informed us that the odds of actually winning an asylum case are less than 10 percent,” says Hinojosa, who has studied Latin America politics for roughly 15 years. “They have asylum cases and asylum claims and have protected status, but they’re not gaining refugee status at the rates they should be.”

A Different Kind of College Course

The social innovation lab is structured unlike a traditional college course in which a professor lectures, assigns regular reading, leads in-class discussion and administers regular exams. Hinojosa, Baker and their students approach child migration in the Western Hemisphere as a design challenge, the tangled details of which are presented using a variety of sources inside and outside the classroom. This is done by blending the use of digital media with traditional classroom methods and providing for some degree of student control over the course’s path and pace. In other words, cultivating a blended learning environment.

Baker brings to the lab her years of experience as an anthropologist and founder of the Reuniting Families Project, established in 2003 as a means of identifying the remains of deceased, undocumented migrants found along the U.S.-Mexico border.

“We knew we wanted to educate our students about child migration and we wanted to empower our students,” Baker says. “We decided that we would have a blended classroom in which we had a few traditional lectures, but much of the class time would be spent in discussion and ideation. The students have had quite a bit to do outside of class in reading and preparation, as well as working on their projects.”

A list of guest speakers who meet with students in person and via teleconferencing grows and changes throughout the semester as students become interested in specific project directions. Essentially, the problem of child migration is deconstructed. Every piece is laid out, end-to-end, so that existing “gaps” in support are more readily exposed.

“When I first saw the course description, it described child migration as a ‘wicked’ problem, and it is definitely that,” senior political science major Delilah Negrete says. “The teachers made it clear to us at the beginning of the semester that this isn’t a problem that’s going to be solved by one winning project, or even in one semester of the course. So that was difficult to wrap our heads around. But, we learned about the problem and identified gaps in aid—the places where we could apply all our varied interests and passions and create viable solutions to fill these specific needs. We’re a mixture of political science majors, international studies majors, psychology, journalism, entrepreneurship ….”

As Negrete and her classmates have worked together to fill the gaps, this particular social innovation lab emphasizes design thinking, an alternative to analytical thinking pioneered by Stanford University’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, commonly known as the d.school.

“Much of the class time would be spent in discussion and ideation.”

“With design thinking, you design it, test it, refine it, test it again, refine it, test it again—that kind of concept,” Hinojosa says. “We encourage the students to think creatively and think without limitations; and, at least at the initial brainstorming phase, we ask them to assume no limits, financial or otherwise. We’ll address limits later. This is what the d.school calls ‘Yes, and’ thinking. Instead of starting with the constraints, we start with the opportunities. We let the students go, working in groups. We really sit back and watch the creativity happen.”

Projects in Progress

Two exciting projects have gained critical mass since fall 2017, when the first child migration lab was offered. Nine students, Negrete included, who completed the inaugural semester of this social innovation lab decided to re-enroll for spring 2018 in hopes of shepherding these projects to completion. Last fall, the class attracted 17 students from seven majors. This spring semester, 23 students, representing 12 majors and including two graduate students, are enrolled.

One such project is a bilingual children’s book, aimed at illustrating for young children the complex legal process they face when seeking asylum and refugee status in the United States.

“My group decided we wanted to communicate the legal system in a way that’s kid-friendly and bilingual,” Negrete says. “We learned about the legal process these children face when they cross the border and how difficult it is for them to keep up with the technicalities of our legal system. If they miss even one step in this process, their case may be dropped. It was very complex for us; imagine an 8-year-old coming from Guatemala who may not have much English, trying to understand all of the details.”

With the help of contacts from the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services’ (RAICES) Dallas branch and Waco-based immigration attorney Analí Gatlin Looper, BA ’07, JD ’14, the team is working on a book that features three to four real-life stories with which a young reader might identify, committing to memory the steps needed to stay on track.

“We spoke with attorneys from RAICES and were told that a lot of times, when migrants come across the border, waiting for their cases to move through the system, they run into issues that hurt their asylum cases like dropping out of school, using drugs, and so on,” Negrete says. “We also want to get some life-coaching content into the book to show kids what they have to do once they’re here as well as what the legal journey looks like and also what it looks like at home, living here as they wait for their cases to proceed.”

“My group decided we wanted to communicate the legal system in a way that’s kid-friendly and bilingual.”

One possible benefit of such a book is that children may keep it. As attorneys from RAICES have shared with Baylor students in the lab, it is common for people from legal aid to go into detention facilities near the border and offer a brief, verbal presentation outlining an immigrant minor’s rights. Then, the presenter is gone.

“The children don’t have anything with them to look back on and remember all of the details,” Hinojosa says. “Our partners at RAICES are really excited about this book project; they want to beta test it with their clients and then they want to get it into all the shelters they serve and the detention facilities. This is going to happen.”

Hinojosa is looking for artists and storytellers who can “adapt legal jargon into content that engages Spanish-speaking children.” He adds that RAICES attorneys will verify the accuracy of legal content. A publisher still needs to be procured, but Hinojosa assures students that the financial bridge will be crossed when necessary.

A second project nearing fruition involves “Northern Triangle,” an artistic collaboration that features artifacts and found objects, drawings by migrant children in detention centers, photographs, paintings and other media—a visual and spatial experience that weaves for the public a story about the ongoing exodus of unaccompanied minors from Latin America.

Among the lead artists whose work is featured in “Northern Triangle” is Mark Menjivar, BA ’02, San Antonio-based artist, and assistant professor at the Texas State University School of Art and Design.

Junior political science major Caroline Capili, whose group has focused on solutions that raise public awareness of child migration, invited Menjivar to speak to her class via Skype. Menjivar went one step further and offered to bring his exhibition to Baylor.

“We’re working with the Mayborn [Museum] right now, working up contracts; we’re looking at the different pieces featured in the exhibition,” Capili says. “Since this is such a complex and heavily political topic, it’s not something you can easily talk about among big groups of people. With an art show, however, we’re hoping to foster big discussions about the issue. We’re hoping people come to consider and understand views that differ from their own.”

Capili’s team is also thinking about a number of events that would supplement “Northern Triangle,” hoping Menjivar and selected figures from the Baylor and Waco communities might give individual talks or participate in a panel discussion. Though the logistics are yet to be finalized, Menjivar and the lab students hope an exhibit occurs later this spring.

“We’re hoping people come to consider and understand views that differ from their own.”

“‘Northern Triangle’ looks at the history of U.S. intervention in Latin America over the past 100 years and how that relates to the refugee crisis happening at our border right now,” Menjivar says. “If you look back at the history of U.S. intervention during the 1970s and ’80s in particular, you will begin to find that our stories are so intertwined it’s impossible to untangle them.”

Emphasizing the dire urgency, Menjivar, whose father is from El Salvador, is adamant that the problem must be discussed as nothing less than a refugee crisis.

“I was there during the civil war in El Salvador; I’ve been inside detention centers for youth who’ve been detained at the border, and I’ve heard their stories of violence,” he says. “I’ve worked annually with a community in El Salvador affected by violence, so the stories of the horrors happening there are real. The reason it’s important to talk about this as a refugee crisis is because they are not just coming to the U.S. looking for opportunity or a better life. We’re talking about tens of thousands of women and children fleeing extreme violence that is happening around them on a daily basis.”

A third project, an asset map, is in progress and has required the research and participation of the entire class. An asset map is intended to identify the individuals, groups, institutions and organizations who are already serving various needs, either formally or informally. It is the kind of project that is never fully complete, Hinojosa says, but at this point, the class has made tremendous progress.

“The asset map has really been our first priority all along,” Hinojosa says. “We started looking at who in Texas is working in this space. Who’s providing legal services? There simply aren’t enough immigration attorneys to go around.

“Who’s providing psychological and physical care for these minors? Who’s providing trauma care, given the horrors of what these minors have seen and experienced? Who’s providing direct assistance—food, blankets and etcetera? Who’s helping with family reunification? Who’s working on education, work opportunities, things like that? We’re trying to build a firm map of who’s working in these areas, where they’re located, and in so doing, trying to identify more gaps previously overlooked.”

Baker is proud of how Baylor students do not shy from tackling major issues.

“Our students are extremely bright and talented and have a capacity to contribute to the world well beyond what they imagine possible,” she says. “Relentless determination is a product of their faith in God. They know that they are His instruments and that all things are possible.”

Unequivocally, this experiment in social innovation has proved as successful as anyone could have hoped, especially for Hinojosa, for whom the lab has been a mountaintop experience.

“This has been the most rewarding teaching experience of my career,” he says. “I am inspired by how hard these students are working and by the ways they are using their creativity and academic training in the service of others.”