Lament, Faith & Restoration

From refugee to coordinating worship initiatives at Baylor, Carlos Colon has experienced loss and lament, yet his faith in God also led to restoration and hope.

familiar thread runs through the tapestry of Carlos Colón’s story. It is one of loss and lament, but his faith in God makes it one of restoration and hope.

Colón, coordinator of worship initiatives on the Baylor Spiritual Life team, was born in El Salvador and as a young boy witnessed his country inflamed in a civil war. Mere hours before a death squad broke into their home, the then 14-year-old Colón escaped with family members to neighboring Guatemala.

While some members of his family obtained visas to migrate to the United States, Colón did not receive permission to join them until being admitted as a student to Belmont University at age 19. He found his way to Baylor as a graduate student and earned a master’s degree in music.

“Simply put, I am a refugee,” Colón says. “Some would say ‘immigrant,’ but the difference between a refugee and an immigrant is that refugees don’t choose to leave. Circumstances force them out. Even though I am a U.S. citizen now, in a sense I am still a refugee.”

For this reason, the Psalms of Ascent in the Bible have become important to Colón’s life “because they are pilgrim songs,” he says. “I not only live with a sense that I’m a stranger in a strange land, but I also live with the reality that as I tell my story, I have many friends who did not live to tell the tale. There are times of deep reflection; I was no different from my friends. We made it out, but they did not.”

Colón said there are many possible responses, including guilt, but he is led to gratitude “and a constant sense that I’m here for a reason. I can spend long nights wondering about that reason, but I’m reminded every Sunday at church that the reason I am alive is to love and serve God and love and serve others,” he says.

On a weekly basis at Baylor, Colón supports University Chapel services and assists Dr. Burt Burleson, University chaplain, and Dr. Ryan Richardson, associate chaplain and director of Baylor Chapel. In the past two years, however, a larger component of Colón’s work has become shepherding chapel alternatives—options for Baylor students to fulfill their chapel requirement rather than the traditional setting in Waco Hall that many alumni know so well. The current three sections per fall and spring semesters of Baylor Chapel, considered the oldest tradition of the University, usually have 1,200 to 1,500 students per section.

Chapel alternatives are “prayer services where the students, instead of going to the big chapel for their semester credit, can go to either morning or evening prayers in a smaller, more personal venue for their chapel experience,” Colón says. “These prayer services are modeled primarily as Scriptural services where students go and learn about how to pray and worship through the Scriptures.”

Colón oversees nearly 30 such chapel services around campus, held in the various smaller chapels—such as Memorial Chapel, Robbins Chapel and Elliston Chapel—and in various spaces within residential halls. Colón leads several of the gatherings himself, but he also has a core leadership team of several students from George W. Truett Theological Seminary as well as some faculty members and undergraduate students who help facilitate the services.

“Chapel alternatives—these smaller gatherings around campus—have allowed students to develop closer and more relational communities of prayer and worship,” Colón says, adding that introducing a liturgical aspect to spiritual formation has added great depth for participating students.

“Liturgy is Scripture enacted,” he says. “We use gestures to welcome God, or to join God who is welcoming us. We sing a gathering hymn or song, then pray a psalm—offer prayers of intercession for one another and for the community and the world. We read a Gospel, pray the Lord’s Prayer and sing a sending song or hymn and close with a benediction from Scripture, sending the people back to their areas of service, whether it’s studying or work.”

Colón says he has seen the smaller chapel format function similar to small-groups found in many churches by fostering a desire among Baylor students who are seeking deeper connection and community through their worship experiences. His desire is that students seeking spiritual connection will be able to discover an option that works best for them at Baylor.

“These chapels have allowed us to help many students know God more personally,” he says. “We see a lot of students attending these services now who are not required to attend chapel.”

As an example, he notes approximately 30 students are officially registered for morning chapel in the Honors Residential College and about 65 registered for evening chapel.

“But there—where the students are leading more and more worship—will be services sometimes with more than a hundred students in attendance,” Colón says.

He says this type of spiritual growth and pursuit is what Spiritual Life aspires to foster.

“I strongly believe that if a university is going to call itself Christian, at the heart there is going to be a commitment to Christian worship,” he says. “What we really want to do is embody the response to our Lord Jesus Christ with the request ‘Teach us to pray;’ something at the core of Christian discipleship.”

Hand in hand with spiritual formation and developing a lifestyle of prayerfulness and worship, Colón says it is equally important to walk alongside students as they develop vocation and teach them how to do that through a spiritual framework.

“We are so conditioned in the West to stress out about what we are supposed to do [after college],” Colón says. “I believe that Jesus Christ is more concerned about who we should be—and that is that we should be holy as He is holy. That should be our ultimate vocation, to pursue holiness. In essence, that is what worship is—praying to God, finding Him in the hymns and the songs and pursuing Him. Within that primary vocation, we find wisdom and inspiration for a secondary vocation—the ways in which we will serve Him.”

Considering his background, Colón could have easily become a political activist or humanitarian. But music is what God gifted to Colón, an instrument he has used to bridge a gap and bring attention to places of need in ways that outshine activism.

“I grew up in a Marxist family in El Salvador, so I suppose I could have easily become an activist,” Colón says. “There is a temptation a lot of times, and there have been opportunities for me to speak publicly about certain issues. I don’t do that. But I can write a song. God can use that as an agent of healing as He sees fit.

“Music is so powerful. I don’t want to use the word ‘weapon,’ but it can do so much. Art—not just songs—can be such a place where God can mediate healing. Some of my music has approached themes and events that are tremendously politically charged but turned it in another direction. Isn’t that what our Lord did? The cross was a symbol of shame and disgrace and Jesus took it and turned it into the symbol of the biggest ‘I love you’ in the universe.”

As a composer, Colón’s music has given voice to issues of social concern and global tragedy. His work has been performed around the world in places like Carnegie Hall and the United Nations as well as numerous performances around the United States, Guatemala and in his native El Salvador.

“Music and the arts in general provide an opportunity for people to see God at work and to connect with one another,” he says. “All of us have an ingrained need to be creative. I am in a unique situation because I am a classical composer, but I’m also a composer for the church, so I bridge these two worlds.

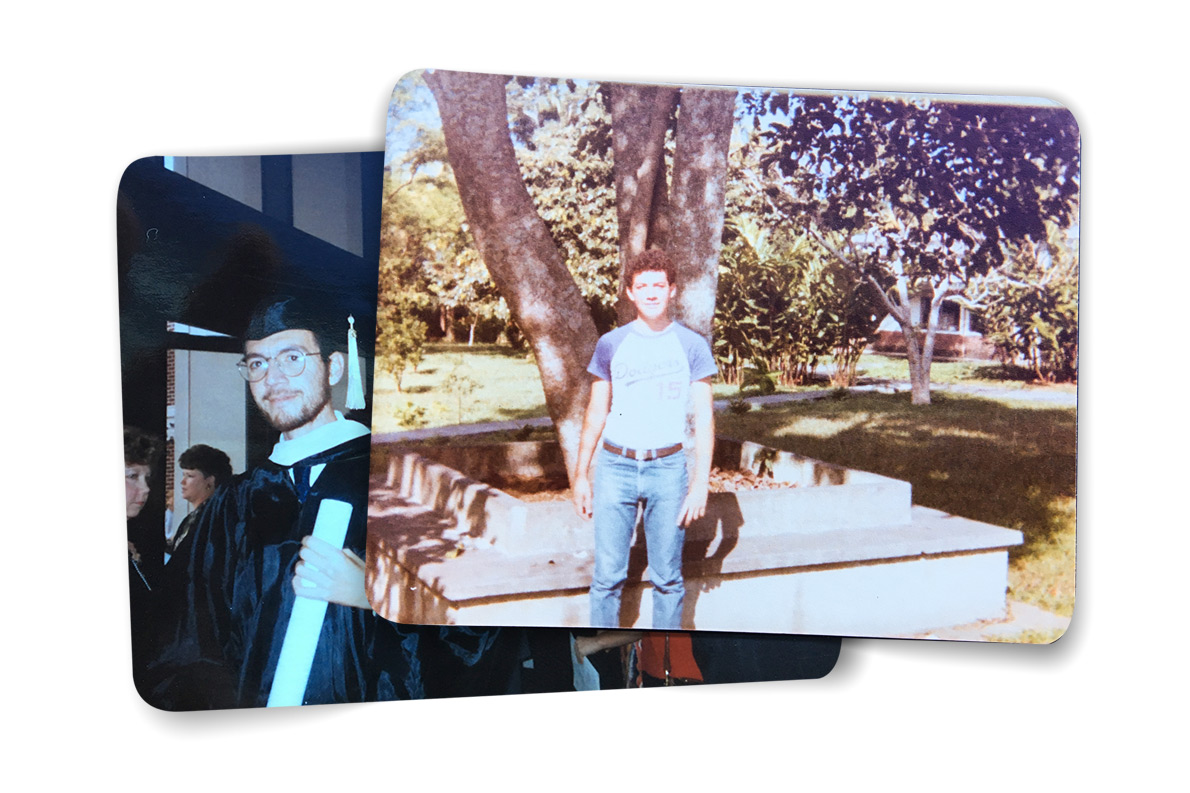

(Left) Baylor Graduation, 1993 (Right) Refugee in Guatemala, early '80s

“I am blessed by working in the church, which by design is made to work in community. As a byproduct, when I’m working in the concert world, people notice that I find ways of connecting them to the music, or I touch on themes that touch on the social concerns or the desire for sacred things.”

Colón’s music has found esteem from his pursuits as well as through his passion of giving a voice to the voiceless.

In 2014, moved by the plight of immigrants crossing the southern border of the United States from Central American countries by way of Mexico, Colón and a documentary filmmaker told the story of the work of Dr. Lori Baker, Baylor professor and forensic anthropologist. Baker leads the Reuniting Families Project, a painstaking process of gathering and analyzing the DNA of unidentified bodies found along the U.S.-Mexico border. The information is entered into missing person databases and shared with groups representing families of the missing with the goal of identifying the deceased for their loved ones.

The documentary — Lamento con Alas (Lament with Wings) — incorporates a musical score composed by Colón, a mournful cello arrangement titled “With My Lost Saints” and choral sections of Colón’s previously published requiem.

“I wrote the requiem—by definition a collection of Christian prayers of remembrance for the dead—for the victims of the war in my country,” Colón says. “The requiem is full of Christian prayers, passages from the Psalms and other Scriptures.”

Colón’s requiem premiered at Baylor before it was presented in El Salvador and several U.S. cities. It became what Colón calls a “postmodern piece” as a lament for a war that resulted in more than 70,000 deaths over 12 years.

“Unbeknownst to me, from that point on, we would be witnessing in our time so many tragedies,” he says, referring to the plight of immigrants and unaccompanied minors crossing the border into the United States. “There have been many opportunities for this art form to help connect people, especially among Latin Americans, and give voice to their lament of war and loss, for example.”

Following a performance of his requiem in El Salvador, the Central American country’s president and first lady asked Colón to write a lament in memory of El Salvador’s beloved archbishop. Since then, Colón has written more church music, setting songs of lament from Scripture to be used in worship services.

Colón doesn’t shy away from expressions of grief and lament. He says such expressions are a sacred element of worship that is often overlooked and missing in the evangelical church today.

“Lament and grief are reality,” he says.

This is something of which Colón knows all too well. In 2012, he experienced the death of his wife and the mother of his two twin daughters, Dr. Susan Colón, who was a faculty member of Baylor’s Honors College.

“Journeying through so much in my life, through two wars—nothing could have prepared me for losing my wife,” he says. “My daughters know what lament is, but they also know hope. Just as we have songs of lament, the Scriptures also have God turning our mourning into dancing.

“I believe we have a real problem with our churches when there are no expressions of lament in our services,” he says. “I believe

we show a depth of poverty in our worship when we think that every Sunday needs to be like a pep rally. We need to put ourselves in the proper place of submission and humility in worship.”

Leading worship in the country of his birth opened Colón’s eyes further to the reality of Scriptural expression of lament.

“We were leading at a church near the Guatemalan border in El Salvador on the last trip I was able to take with Baylor before it became too dangerous to go back,” he says. “In our liturgical worship, we were singing Psalm 120, which says ‘Woe to me when I dwell among those who hate peace. I am for peace; but when I speak, they are for war.’

“I realized that we were among people who intimately felt the feelings and despair behind those words; people who are harassed every day by violence and the threat of death. These people were living the words of this psalm in a relevant way.”

Colón quickly points out that the need for lament and repentance is not found only in the mission field among countries ravaged by civil war.

“As the language, the violence and the contention in our country has continued to grow and as believers of Jesus are continually marginalized from left- and right-wing ideologies, I think we need more prayerful language to be able to process and prophetically pray this message of repentance in our society,” he says.

“Many times, we do not contribute or speak up because we surrender this prophetic voice to ideologies. It’s a problem, because then we are not being representatives of the King. The church has suffered many martyrs who are around the throne of Christ because they refused to make someone else king except King Jesus. Should we not do the same?”

Colón also acknowledges that Baylor has not been immune from crisis and has at times reflected the tense climate of the nation.

“Baylor is such a big place,” he says. “From my perspective, events that have happened over the last couple of years have prompted a lot of people around me into deep reflection, much like the aspect of the Christian walk that asks, ‘How then should we live?’ When there is confusion and distraction from the mission of the church and the Christian institution, there must be a refocusing. Where does that start? It should start with worship, with prayer and reading of the Scriptures, with humbling ourselves before God. I believe that is happening at Baylor.”

Outside Colón’s office in the Bobo Spiritual Life Center are comfortable couches and café tables draped with students studying, huddled in groups in quiet conversation or enjoying a moment of quiet reflection between classes. Colón says it is a constant prayer of the entire Spiritual Life team—as it is with many others in leadership across Baylor—to remain vigilant in assisting students as they grow academically and spiritually.

“Baylor has been a place where I have found amazing friendships, both with students and my colleagues,” he says. “I think Baylor has a wonderful calling and opportunity to join God in the formation of Christian men and women. My hope is that we will find ways as we love and serve God to continue this mission.”

Baylor students, faculty, staff and alumni regularly sing That Good Old Baylor Line, but Colón emphasizes an understanding of a particular line from the song.

“How will Baylor go about lighting the ways of time? What will we do with this amazing opportunity of being here at Baylor at this point in history, as the largest Christian Protestant university in the land? What will we do with these amazing students who come to us from all over the world?

“We are stewards of a great treasure,” Colón says. “That’s something that all of us, from top to bottom, are consumed with.”

Colón and a group of 30 students from the Honors Residential College chapel led worship and prayer for the Baylor Board of Regents during Homecoming week in October.

“This is the group of people that gave the green light five years ago to allow the chapel alternative program,” Colón says. “It was a moment filled with a lot of hope for me. If spiritual moments like that among students and leadership can be happening 100 years from now, we’re going to be the same Baylor, lighting the ways of time and changing the world, just as the founders intended. If worship and prayer and the Scriptures remain at the core, as the fiber of who we are, we will be OK.”