Opening Doors

Hankamer School of Business faculty and graduate students work with the Prison Entrepreneurship Program to help parole-eligible inmates understand the importance of integrity and accountability as they gain the skills and confidence for success in the business world upon their release.

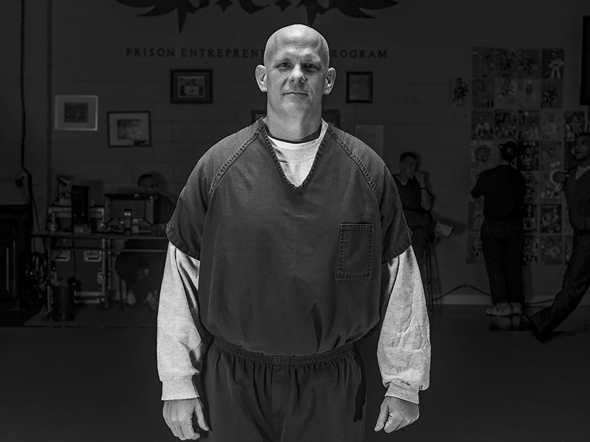

Bryan Kelley was denied parole 12 times. But when his 13th attempt was successful, Kelley threw the parole commissioner for a loop by asking that his parole be deferred for a year.

“He looked back at me and said, ‘I’m telling you that you’re getting out. Why are you bargaining for next year?’” Kelley says.

What made Kelley want to spend another year in prison—his 22nd year of a life sentence for a drug-related murder in the early 1990s—was the Prison Entrepreneurship Program (PEP).

A Houston-based, Texas-specific program, PEP builds an understanding of the importance of integrity and accountability in parole-eligible inmates, while equipping them with the skills and confidence for success in the business world upon their release. Faculty members and graduate students from Baylor’s Hankamer School of Business have been working with PEP since 2007.

Kelley’s request was granted, and he remained incarcerated an additional nine months. This additional time allowed him to develop a business plan through PEP. Kelley, who worked as a peer educator during his last seven years as an inmate, has continued to work with PEP since his release from prison. He works as a re-integration manager, organizing events at the Estes Unit near Venus, Texas, and leading a re-entry team that helps ensure success upon a PEP graduate’s prison release.

Kelley says the most important aspect of PEP comes at the beginning of the program, when employees and volunteers spend the initial months of the nine-month program on character development.

"We have to start with that foundation of strong character. We’re trying to train men to be leaders in their home, in their community, in their workplace."Bryan Kelley

“We can teach you how to run a million-dollar business, but if you don’t have the character to support it, you’re going to crash and burn in a bigger fashion,” Kelley regularly tells inmates at the beginning of their PEP experience. “We have to start with that foundation of strong character. We’re trying to train men to be leaders in their home, in their community, in their workplace. Once that foundation is built, then we start the business plan formation.”

Not Just a Program, a Revolution

Established in 2004, PEP is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that receives no state or federal funds. Its beginnings can be traced to the Hamilton Unit in Bryan, Texas, before moving to the Cleveland (Texas) Correctional Facility. The Estes Unit was added in 2015, and PEP hopes to expand to more Texas prisons soon.

PEP is not open to death-row inmates or those who have committed sex crimes. Typically, applicants are within one to three years of parole eligibility; although, as in Kelley’s case, parole timetables are not an exact science.

Roughly 500 participants are chosen yearly out of more than 10,000 eligible inmates, giving PEP an acceptance rate more selective than most prestigious universities. Participants are chosen for the program after a screening process that includes a 20-page application, three exams and an interview with PEP staff members.

According to the PEP website (PEP.org), it is more than a program—it is “a revolution, achieving amazing results with profound impacts.” PEP connects convicted felons with entrepreneurs, MBA students and some of the nation’s top executives.

“We bring in a lot of folks from the business community and run Shark Tank-type events or business-plan workshops,” Kelley says. “MBA students are typically their business-plan advisors and help them critique their business plan. PEP participants get a lot of input from different places—from folks who are in the business community—on the practicality of their business plan.”

Bert Smith, who became CEO in May 2010, has worked with PEP since 2005 in various volunteer roles, including executive judge, business plan advisor, teacher, mentor, donor and chair of the Houston Advisory Board. PEP also has a North Texas Advisory Board and a National Advisory Board.

PEP’s eight-person governing board also has strong Baylor ties, including Robert Barkley, BBA ’78, JD ’80, John Jackson, BBA ’79, and Hankamer Associate Dean Gary Carini.

According to Carini, PEP has been contacted by law enforcement and prison wardens from across the world to discuss the program, including a sheriff in North Carolina and a prison administrator in Europe.

“Bert Smith keeps strong relationships,” Carini says. “Every time I’ve gone into a prison with PEP, even the interaction with the guards, you can tell they’re glad we’re there.”

The three-month Leadership Academy begins the program. Participants attend character-development and computer-skills classes. It is in these classes that participants are exposed to PEP’s 10 driving values: fresh-start outlook, servant-leader mentality, love, innovation, accountability, integrity, execution, fun, excellence and wise stewardship.

What follows is a rigorous six-month “mini-MBA” program with classes taught by PEP staff, board members and business executives. The program uses college textbooks and incorporates business school case studies from Harvard and Stanford. Participants also have access to literacy and business etiquette classes, employment workshops and Toastmasters.

There is a graduation ceremony at the prison, and family members are invited to attend. Carini, who has attended many of the biannual graduations, says the prison gymnasiums are packed for the events.

Participants are selected from prisons statewide and assigned to either Cleveland or Estes. Kelley says a participant’s transformation—beyond his business savvy—is remarkable.

“When they start PEP, they are broken,” he says. “They are an empty shell of a human being that cannot look you in the eye and convey a thought because they are so ashamed of who they are. They typically cannot put more than a few words together without looking down in shame.”

Nine months later, a completely different man appears.

“That same man will stand up before a panel of successful businessmen and women and give a 10- to 12-minute business pitch, complete with his product or service offering, his industry, his competitors and a three-year performance estimate,” Kelley says. “He will talk about philanthropy, and he’ll do this with great passion and knowledge. The transformation in those nine months in the level of confidence and competence is remarkable.”

Although PEP is not a faith-based organization, Kelley says it is spirit-infused. He believes Christ’s hand is evident in the transformation process.

“In the first three months, we teach the men what it is like to be a godly man, an honorable man, and we pull those truths from the Bible,” Kelley says. “We pray in and out of every single meeting that we have; we have a devotion during every single class. The men and women who come into the prisons to invest into the inmates’ lives are almost all Christian, so that becomes very apparent where the spirit and truth is coming from.”

Part of the Solution

Jackson approached Carini in July 2007 about the possibility of getting Hankamer graduate students involved with PEP. Carini joined Jackson and another PEP executive at the Hamilton Unit for two days later that month, observing and participating in the business-plan competition.

“I was seeing their finished products along with at least 50 other people that were there from outside the prison, sitting as judges on panels to determine the best business plan,” Carini says. “I was thoroughly impressed. Right away, I knew we had to get involved.”

Carini hoped that five or six students would volunteer with the program that fall. Close to 15 participated. The next fall, nearly 25.

Laurie Wilson, BBA ’84, MBA ’09, is director of Baylor’s graduate business degree programs. She says most applicants already know about Hankamer’s PEP involvement.

"Every time I’ve gone into a prison with PEP, even the interaction with the guards, you can tell they’re glad we’re there."Gary Carini

“They always ask because they want to be a part of it,” Wilson says. “The type of student that Baylor draws and this generation of young professionals, they want to give back to their community. They want to be a part of a school that believes in that.”

Wilson says most students volunteer with PEP in their first semester at Baylor. The students review a PEP participant’s business plan, edit it, comment on it and send it back to PEP, which then delivers it back to the inmate. Carini says the marketing section of the business plan is where students and business executives lend the most assistance.

“If you want to launch a brick-building business in Plano, the prisoners don’t have access to who’s in that market competing and what the prices will be,” Carini says.

Students have the option of going with Carini to the prison where they take part in the actual business-plan competition. Site visits are not required, but Carini says many students want to participate in the on-site events. He remembers a female MBA student who visited the Hamilton Unit with a group of about 10 students in the early days of Baylor’s involvement with PEP. Carini remembers the immediate impact the visit had on her.

“When we got back to our cars, I asked the students what they thought,” he says. “She said she was in a crummy mood before we went to the prison. ‘I didn’t want to come down here. I don’t have time for this.’ She said she was in the prison for maybe 20 minutes of our three hours there before she was on the other side. She said she realized it was where God wanted her to be, that she was being blessed by serving. I was seeing a heart transform right at that moment.”

Carini himself has been blessed by his work with PEP. He remembers a conversation over lunch with an inmate.

“After 15 or 20 minutes of conversation, I said, ‘You seem happy, you seem content, and you’re in prison,’” Carini says. “And he said, ‘But this is where God wants me. I am content. I get to be here in His sovereign will.’ That really spoke to my heart. God has put him there for a reason and to serve other prisoners in the Lord. That does it.”

Kelley appreciates Baylor’s involvement with PEP and encourages students to visit the prisons for face-to-face meetings with the men they have helped via email.

“Students become business-plan advisors, and it’s basically their first consulting gig,” he says. “It may seem like you’re just doing a little market research, doing a little critiquing of paragraphs here and there, but you’re helping to shape a man to become what he never thought he could be. When you meet that man, and you see and feel the appreciation, the hope, the excitement of a new life, you cannot put a price tag on that.”

John Pham is a current Baylor graduate student in Hankamer’s healthcare program. A 2016 University of Oklahoma graduate, Pham volunteered with PEP immediately upon beginning his studies at Baylor.

“I saw an opportunity to broaden my knowledge and experience,” Pham says. “The people in prison, that’s a population that probably never crosses most people’s minds. Most people haven’t set foot in a prison unless they’re required to; it’s a totally different perspective. My experience with PEP completely flipped my idea of what prison was.”

Pham participated in a business-plan pitch event at Estes. PEP participants had one-on-one coaching sessions where Hankamer students and business executives helped the inmates better shape their ideas. Pham says most of the business plans he heard that day were viable.

“Probably about 70 percent of them, you’d think, ‘Wow, that’s a great idea,’” Pham says. “Someone wanted to open a restaurant with their grandma’s recipes, and he had strong speaking skills—almost as strong as some of the students here in the program. I was impressed with all the research they had done.”

Pham says the students’ work with the PEP prisoners benefits the students as much as the inmates, if not more so.

“I was able to take some things I learned in school and apply those concepts in a real-life setting,” he says. “I knew that the things I learned and was now applying in giving people feedback was helping them refine their vision and their future. That was exciting and fulfilling.”

The benefits and blessings for Pham went far beyond business and marketing plans. He admits that prior to his visit to prison, he didn’t feel much sympathy for the inmates.

“They went through the court of law and were deemed guilty, so here they are; they’re receiving due justice,” Pham says. “But while I was there, the walls started to come down. I realized that these are people, and they miss their families—they have hopes and dreams, and they’re still pursuing them. I learned a lot about compassion and service and unconditional love. It’s an eye-opening experience, and I became more culturally competent.”

Pham says Hankamer’s PEP involvement is a cogent intersection of business and faith and that his volunteerism helped him better learn how to serve and be led by Jesus.

“Prisoners are stripped of their dignity and integrity,” he says. “But PEP does a great job empowering them and giving them opportunities so they can reestablish their lives when they leave.”

Wilson sees the benefit of the students’ PEP involvement in that realm—a chance to better the community and the individual concurrently.

“You learn about the economic cost of maintaining prisoners,” Wilson says. “These are tax consumers rather than taxpayers. The students get a lot out of it, but that’s what you do when you help your community. You see the problem. You see yourself being part of the solution, and you didn’t even know that problem impacted you personally until you learned about it through this organization.”

In 2013, Baylor began a partnership with PEP to offer inmates who complete the program an entrepreneurship certificate. Carini, who pushed for Baylor to enter the partnership, says about 400 certificates have been awarded to this point.

“It says, ‘Baylor University’ on the certificate,” Carini says. “For them to be able to put that on their transcript is a bigger deal than we realize.”

Hankamer Dean Terry Maness, BA ’71, MS ’72, is pleased with Baylor’s PEP partnership, calling it a win-win for everyone involved.

“It’s ideal as a mission fit for us in the business school in terms of service and wanting to impact society in a positive way,” Maness says. “Anything we can do to help these people transition from being in prison to being positive factors in society is a plus. And it’s a great learning experience for our students. They are applying their business skills in terms of understanding the business plan and packaging something that can work.”

Complete Paradigm Shift

But does it work? PEP’s goal is not simply to give the soon-to-be-released inmate a marginal chance but to prepare them for real-world, post-release success—in the business world and in life.

“Typically, people coming out of prison, the number one question is whether they can get a job that allows them to make a living,” says Byron Johnson, Distinguished Professor of Social Sciences and co-director of Baylor’s Institute for Studies of Religion (ISR). “It’s a tough row to hoe. Some of these guys don’t have a driver’s license, and even getting a residence is a hard thing. But PEP is a complete paradigm shift.”

A recent ISR study shows that the Houston-area unemployment rate is higher for average citizens than PEP graduates.

“You’re finding companies hiring inmates over college graduates. That’s counterintuitive,” Johnson says. “We interviewed business leaders that were hiring PEP graduates. They tell us that kids coming out of college have an idea of what it’s supposed to look like and how they’re supposed to work, but they’re not receptive to how we want them to do our business. PEP guys are.”

PEP reports that 100 percent of those who complete the program are employed within 90 days of release from prison. Nearly 300 businesses have been launched by more than 1,500 PEP graduates, and at least six of those businesses generate more than $1 million in annual sales. Roughly 42 percent of PEP graduates own homes within three years of release.

The most compelling statistic associated with PEP is the recidivism rate. Nationally, released prisoners return to incarceration within three years at a 50 percent rate; in Texas, that rate is 24 percent. However, less than 7 percent of PEP graduates return to prison within three years.

For Johnson, it’s more than low recidivism rates alone; nonetheless, he believes PEP has developed an ideal model.

“Did you get rearrested? No. Does that mean you’re clean? Not necessarily. You’re just beating the system,” he says. “There are other measures like family. Are they going to church? Are they giving back to the community? Are they doing other things that we know to be positive things that help society?”

Kelley entered prison as a drug and alcohol addict—in his words, a shell of a man. His transition to prison life was difficult; he battled depression and slept a lot. Kelley says his PEP success story would not be possible without what transpired about 18 months into his sentence.

“A friend invited me to a prison ministry called Kairos,” Kelley says. “There were discussions about truth and introducing the love of Christ.”

Kelley, a Kansas native, bonded with a Lutheran minister named Keith who was a University of Kansas graduate. Through this relationship, Kelley’s walls began to come down.

“At that point, I had never admitted to anybody that I was guilty of my crime,” he says. “I had steadfastly denied it, even at trial. I couldn’t carry that burden anymore, especially around so many men in the light.”

Kelley confided in Keith, acknowledging in full detail his crime. Keith extended forgiveness but told Kelley that he more importantly needed to ask God for forgiveness, assuring Kelley that God would forgive him. After some hesitation (Kelley did not believe he deserved to be forgiven), he reached out to God.

“I have made a shamble of my life, and all I have to give you is broken pieces. I’m sorry, but here you go. I can’t do this anymore my way,” Kelley, who had brief church encounters as a child but was not a believer, remembers praying. “What a difference that made in my life. He can make a masterpiece out of broken things.”

Kelley eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology and became a college tutor and a PEP peer educator. He began to disciple other prisoners and lead Bible studies. His favorite Bible verse is Ephesians 2:10: “For we are God’s handiwork, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do.” (NIV)

On his final night in prison, Kelley’s cellmate asked if he believed he had to commit murder to become the person he is today.

“No, I regret that tremendously,” Kelley told the man. “I wish that man did not have to lose his life, but I love what God has done in my life and where I’ve come from. It turns out that prison is the best thing that ever happened to me. I have the confidence to walk in faith anywhere and God will be going with me.”

Kelley’s words ring true to Pham, who says he connected with PEP participants in a personal way.

“They’re just people, looking for community,” Pham says. “I was trying to do that at Baylor—I was trying to find community. I was looking for people where I could drop my walls and could do life with them and grow with them. Through my volunteer work with PEP, that really happened.”