50 Years After Graduation

A look at the touchstones of cultural barrier breakers

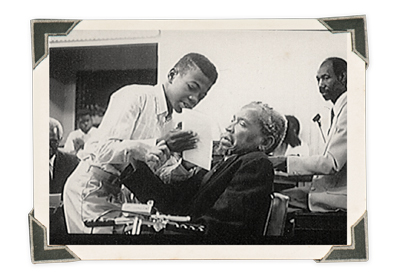

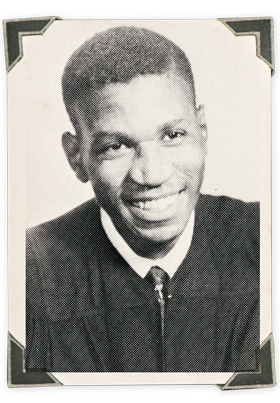

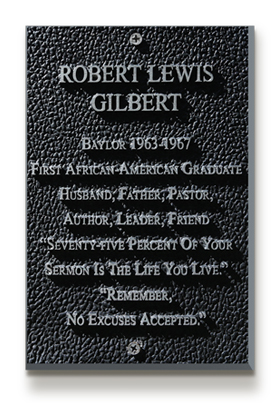

When Rev. Robert L. Gilbert became Baylor's first African-American graduate 50 years ago, he had survived the battles with prejudice and misunderstanding that are common with cultural trailblazers. The challenges he faced as one of the few African-American students at a newly integrated school were only a fraction of the painful struggles that he overcame during his short but eventful life.

Gilbert was born Dec. 27, 1941, in a poor section of South Waco known as "Butcher Pen" because of the many cows and hogs killed by residents for food. He was the next-to-youngest of five children--four boys and a girl--born to Rev. B.F. and Fannie Mae Gilbert, who both had ministers in their family background. Gilbert's father made a modest living as the pastor of two small-town Baptist churches and worked odd jobs to make ends meet.

When Robert Gilbert was a youth, his father suffered a broken neck and developed crippling arthritis that put him on crutches.

Their father was a "strict authoritarian" who also was compassionate, earning the respect of his children in a family Robert remembered as happy. Sunday prayer time and church attendance were mandatory. The Gilbert parents also placed a high value on education for their children. The pastor required each child to tell something they learned that day as the family ate dinner together.

"We also had to read something every day," recalled LaRue Dorsey, Gilbert's sister who became a veteran schoolteacher. "We couldn't even afford the newspaper then, but Daddy worked for white folks and would ask them for the paper after they'd read it. We had to read the paper and tell him something that was going on."

As he grew, Robert observed that black people were often treated as inferiors by whites. At the same time, he heard accounts of men and women during Negro History Week at school and "realized that black people could achieve and do things that were great." The young boy began nurturing dreams of being elected to Congress to fight injustice--an ambition he believed could best be achieved by earning a law degree.

At age 14, Robert contracted arthritis--like his father. It would prove to be the first entry in a lifetime litany of pain and suffering. It initially seemed to be a minor case.

He graduated third in his class at Waco's all-black A.J. Moore High School in 1960, enrolled in Paul Quinn College, an historically black school in Waco, and pursued studies he hoped would lead to law school. In July 1963, however, Gilbert's arthritis changed course dramatically. He was out on a date at a Waco restaurant when his ankle began swelling so badly that he was unable to put any weight on it. A good soaking of the ankle made the swelling and pain disappear, but the next day the swelling returned.

"And then it began to move from one joint to the other, and at the same time my skin began to break out with some bumps and lesions that...finally was diagnosed as psoriasis," Gilbert said.

As both conditions worsened, he endured two years of a grueling series of hospitalizations. Gilbert was sent first to a crippled children's hospital in Gonzales for three months, then to Waco for a two-month stay in Providence Hospital. In March 1964 he was sent to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, where during a seven-month stay his weight dropped to 79 pounds and, according to Gilbert, the doctors finally gave up and "sent me home to die."

Back in Waco, Gilbert decided he was through with taking large amounts of medicine and "lying there in bed helpless." He gave up all medicine, sought help from a local chiropractor and progressed from using a wheelchair to using crutches to walking unaided.

Beginning at Baylor

Gilbert enrolled for another semester at Paul Quinn. He realized that if he wanted to attend law school in Waco, a transfer to Baylor would be his only option. Baylor had the only law school in town, and the university had desegregated its admissions policy in December 1963, with the first black students enrolling in January 1964.

Gilbert was determined to succeed at Baylor, despite his past experiences there.

"I lived my life only about eight blocks away from Baylor, but there was always something foreign, something off-limits about the school," he said in a Lariat interview years later. "I walked through the campus on my way home almost every day, but you almost felt intimidation if you walked through slowly."

Gilbert began at Baylor in summer 1965, and one of his first classroom experiences provided credence to his fears. In a story he would recount many times, Gilbert's first Baylor professor didn't make him feel welcome:

"I went to (the professor's office) to talk about the course and how I could better prepare for it and all. He asked me if I was from around these parts. I said yes, I was a native Wacoan. He said, 'But you don't talk like a n*****.' That rubbed me the wrong way."

A number of Baylor professors did welcome Gilbert. One was Dr. Rufus Spain, now an emeritus professor of history. Spain, who was considered one of the more liberal professors on campus at the time and taught Gilbert in two classes, said he remembers vividly the time Gilbert first walked into his class.

"He was terribly arthritic, and he already was walking with a crutch. My first thought, I hate to admit it, was why are they sending this token student to me? There was almost no integration at Baylor at that time, and to my discredit I thought, well, we're just putting him on display--he's handicapped and so on--and probably won't be a good student," Spain said. "Well, pretty soon I learned that he was a good student."

The two men began a warm friendship that lasted throughout Gilbert's life. Gilbert called Spain his "greatest friend" at Baylor:

"He helped me from the standpoint that he made me feel at ease. He asked me to a faculty luncheon where a famous historian spoke. I was probably the only undergraduate there. I felt a little out of place, but that was one of my peak experiences."

Two other Baylor faculty members Gilbert befriended were history professor Ralph Lynn and religion professor Daniel McGee.

Gilbert concentrated on his studies and did not join any campus organizations while at Baylor. He found that his interactions with fellow students varied.

"In some cases, people went out of their way to say hi. In other cases, I would say hi and they would just ignore me," he said.

One Baylor student who became Gilbert's friend was a white football player from East Texas who began offering him rides home.

Dorsey said, "My daddy told (the football player) that if he brought Robert home or followed him home, we would give him supper every evening. The player said, 'My mother and father will be very unhappy with me, but I was in the service and got to know blacks, and I have no problem with it.'"

Gilbert grew close to John Westbrook, a fellow minister's son who became the first black athlete to see action in the Southwest Conference when he played football for Baylor in September 1966. Gilbert also spent time with Barbara Walker.

"We would set aside time to go to the Student Union to eat together and talk--just share where we were in life," Walker said. "Robert was a very proud person. He didn't want anybody feeling sorry for him. Intellectually, he was so bright and had goals he set for himself. I remember him saying that just because I have a handicap, that doesn't mean I lower my standards of what I want out of life."

Changing Dreams

As Gilbert made his way through Baylor, he acknowledged he would have to abandon his boyhood dream of becoming a lawyer. First, his doctor told him that his health wouldn't allow it. More significantly, by 1966 Gilbert could no longer fight the feeling that God was calling him to a ministry career he had once rejected.

"Robert...did not want to preach. He said there were enough preachers in the family already," Dorsey said. "He made the statement one day that I'll die before I preach, and he almost did. He found out his arm was too short to box with God."

After two years at Baylor, Gilbert completed work for a bachelor of arts degree in history with a minor in English. The commencement ceremony took place June 2, 1967. Since Gilbert's name was called alphabetically before that of Barbara Walker, he became Baylor's first black graduate and Walker became the second and the university's first female black graduate.

"They said don't clap until everybody was graduated, but it was like a wild stampede. There were so many people, our church members came, family, and when they called his name people started clapping," Dorsey said. "I thought, oh God, I hope they don't put us out of here. But we were so proud of him because he was the first, you know."

While the Gilbert and Walker families were spreading the news about the significant racial milestone, the local media was virtually silent. Not a single mention of the graduation of Baylor's first African-American students was made at the time in the Waco Tribune-Herald, the Waco News-Tribune, the Baylor Lariat or in any official Baylor news release.

Gilbert quickly followed his historic achievement with another, becoming a teacher at Waco's Tennyson Junior High and that school's first black faculty member.

During the summers following his Baylor graduation, Gilbert became an instructor in the Upward Bound program at the university. Upward Bound is a federal program that helps high school students from low-income families prepare for college.

Gilbert also began preaching part-time in local churches, and he decided to become a full-time minister. In 1970, he enrolled at Baylor hoping to earn a master's degree in Biblical studies, and he accepted Baylor's offer to serve as the assistant director of Upward Bound.

But the arc of Robert Gilbert's life was about to take a steep plunge. In April 1971, his health failed as the arthritis and psoriasis that had plagued him since he was a teenager returned with intensity. He was forced to drop out of the master's program and spend the remaining 21 years of his life in a constant battle with an ever-increasing number of physical challenges.

During the last 35 years of his life Gilbert was hospitalized 65 times for a list that included congestive heart failure and an enlarged heart requiring open heart surgery, two colon operations, two hip operations, including the installation of an artificial hip, glaucoma in both eyes, pneumonia, high blood pressure and a stroke caused by a blood clot. At one point, he required hospitalization when a mistake by his dentist resulted in him receiving penicillin, to which he was allergic.

"I thought he would have died 10 or 20 years sooner than he did," Spain said. "He's one of the most admirable people I've ever known--the fact that he would carry on with such handicaps."

Living No Excuses

Despite his pain, Gilbert did carry on. He became the pastor of three churches, including Waco's Carver Park Baptist Church from 1978 to 1989. In 1976, he was the first African-American elected to the Waco Independent School District school board.

He also became one of Waco's first civil rights leaders, seeking to guarantee local African-Americans equal wages, more access to jobs and careers and educational opportunities equal to those available to white students. In the 1970s and 1980s, he sometimes turned his attention to Baylor, advocating for the hiring of African-American coaches and lobbying the university to integrate its board of trustees.

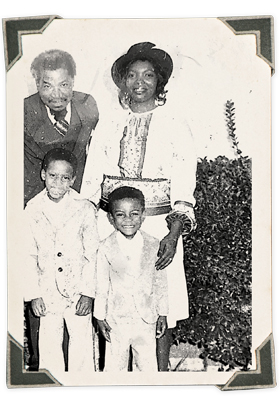

"He deeply admired Dr. Martin Luther King," said Gilbert's son Kenyatta. "I think he saw himself as being someone who could speak to some of the social ills...He was always seeking to better the life of the least of these, which is very consistent with Dr. King's vision." Kenyatta added that his father had a "quiet militancy" that had not been seen in many black leaders in Waco before that time.

As Gilbert increased his church and civic commitments over the years, his health continued to decline.

And as he expanded his public presence, Gilbert's unflinching stand for civil rights made him enemies.

"When we were young, people would call on the telephone and try to scare my family," his son JaJa Gilbert said. "They would hang up and not say anything, and my dad would call out, 'you cowards!'"

Gilbert received hate mail, and family members said one time an unknown person set fire to his home while he was in it. Neighbors were able to intervene before the bedridden man was injured or the house destroyed.

The title of Gilbert's 1988 autobiography--No Excuses Accepted--summarizes his life's philosophy.

"No excuses accepted--he meant that," Gilbert's daughter Evangeline Slaughter said. "No matter what pain, no matter what hurt or disparities were in your life, if you were poor, if you were ugly--it didn't matter. You could fight any challenge that was before you. He taught me that."

"He always believed there were no excuses for not being able to do what you set out to do, because he believed that with God, all things are possible," his wife Elwayne Gilbert said.

Robert Gilbert died Nov. 11, 1992, at age 50. Three weeks earlier, he had been honored as Humanitarian of the Year by the Waco Conference of Christians and Jews. More than 1,000 people attended his funeral in Waco Hall on the Baylor campus.

"The Rev. Robert Gilbert was literally God's suffering servant," said then Baylor President Herbert H. Reynolds in a tribute.

While Gilbert began his family's ties to Baylor, his children have strengthened those ties.

Daughter Evangeline earned a bachelor of science in education from Baylor in 1999 and has served the last 17 years as an administrator with schools in Orange County, Fla.

Son Kenyatta came to Baylor in 1992, was active in campus groups such as Alpha Phi Alpha and the Heavenly Voices Choir, and graduated in 1996 with a bachelor of arts in political science. He has a passion for preaching, teaching and researching.

Kenyatta earned a doctorate in practical theology from Princeton Theological Seminary and is an ordained minister. He serves as associate professor of homiletics at the Howard University School of Divinity and, like his father, is a successful author. His newest book, A Pursued Justice: Black Preaching from the Great Migration to Civil Rights, was published in 2016 by Baylor University Press. The book was inspired by his father's embrace of African-American prophetic preaching with vision for justice and priestly concern for victims of circumstance.

"His imprint is pretty large," Kenyatta said. "His legacy lives on in people, and I would just say that if you talk to any minister who knew him, they would say that they had gotten more courage and inspiration by looking at his life and how he lived it."

Two trailblazers graduated from Baylor June 2, 1967

Minutes after Robert Gilbert became the university's first African-American graduate, Barbara Walker received her diploma and became Baylor's first female African-American graduate.

While Gilbert and Walker shared the stage at that historic commencement, their experiences at Baylor were quite different. Gilbert remembered his Baylor years as a time of struggle against both racial prejudice and physical disabilities, and he didn’t join in many campus groups or activities. By contrast, Walker looks back fondly on her Baylor years as a time of exciting personal growth when she found good friends among students of all races.

"I loved Baylor," Walker said. "It was wonderful."

Walker grew up in the small town of Redbird in northeastern Oklahoma--one of more than 50 all-black communities founded during the days when Oklahoma was a U.S. territory.

While Walker started out attending an all-black high school, "when integration came we lost our high school and consolidated with Porter High School, which was an all-white school," she said. "Porter really prepared me for Baylor (by) being in an environment with others who were different than me."

Walker first attended Paul Quinn College, where she majored in mathematics. A white history professor at Paul Quinn recognized Walker's exceptional abilities and urged her to transfer across town to Baylor.

"He sat me down and told me, this is not really where you need to be," Walker said. "(He said) I know that Baylor is going to be integrating, and I want you to be prepared to go there next year."

Walker's math professor at Paul Quinn also urged her to go to Baylor, so she enrolled in fall 1964 as a sophomore math major. Although she was one of a very few African-American students on campus, Walker was not apprehensive.

"I understood that the student body on two separate occasions had voted to integrate...so I felt that (they were) pretty much ready to receive African-American students," Walker said. "I never thought that would be an issue for me."

Far from avoiding contact with white students, Walker immediately sought them out.

"The summer before I got to Baylor they informed me that I had been assigned a private room. I wrote back to them and told them I thought Baylor was integrated, and that I didn't understand why I was being separated," Walker said. "I understand that a dean during one of the meals told (a group of white female students) that a Negro girl was coming in the fall, and asked if anyone would like to be her roommate. Several people volunteered, but the one who followed through and became my roommate was Barbara Blair from Alabama. We got along really good together."

During her three years at Baylor, Walker roomed in Memorial Hall--first with Blair, then with another white female named Carol Steckline and later with a group of women in a suite. Walker said she enjoyed her time in Memorial.

"Mrs. Cox, the dorm mother, and everyone else in the dorm went out of their way to make me feel welcome," she said. "They weren't rude at all...it was a positive experience for me."

Walker said she never had the anxiety that some African-American students felt at other newly integrated universities at the time.

"During the 1960s, when integration was taking place, it was quiet at Baylor. There was not that animosity, so I didn't have to feel tense or nervous wherever I went," Walker said. "I could walk on campus by myself in the evenings (without a) thought of any kind of danger or anybody saying or doing anything to me."

Soon after she began her Baylor studies, Walker realized that her calling was in social work, so she changed her major from math to sociology. (Baylor had no formal social work program at the time.) She has fond memories of Dr. Harold Osborne, a sociology professor who helped change her career path.

"I've never regretted going into sociology. Dr. Osborne helped in guiding me toward graduation and looking at what was beyond that. He talked with me about getting into graduate school and what were good places to apply to," Walker said. "He played a major role in my future."

After graduating from Baylor, thanks in part to help from Osborne, Walker went on to earn a master's degree in social work from Florida State and served 32 years as a licensed clinical social worker.

While her Baylor professors were never rude to her, Walker said most of them didn't go out of their way to be welcoming, either. But there were notable exceptions.

"My first year at Baylor, I took English under Ann Miller. She was the most wonderful woman I've ever met in my life," Walker said. "She was very nice and open with me and made me feel welcome in her class."

Walker enjoyed learning political science from Ann Miller's husband, Dr. Robert Miller.

"I was quite fond of both Dr. and Mrs. Miller," Walker said. After becoming friends with members of the Chis--a women's social service club--Walker during her senior year decided to apply for membership. To her surprise she was accepted and became the Baylor group's first African-American member. She took part in the club's performance in the 1967 version of All University Sing. To her knowledge, she was the first African-American to perform in that beloved Baylor production.

When it came time for her to graduate, Walker remembers being treated like any other Baylor student, despite the cultural importance of the event.

"For me it was a normal graduation because nobody made a big deal out of it. Nobody talked about it at Baylor," she said. "Nobody paid any special attention to me at all."

Since her graduation, Walker has been invited back to Baylor a number of times to speak to audiences in Chapel and at Martin Luther King Day events. She now has a grandson attending Baylor, and she plans to publish a book about her life and her experiences at the university she cherishes.

"I love Baylor. Baylor opened up opportunities that I would have never had otherwise," Walker said. "I felt Baylor was a very safe environment for me. It was the place where I got to grow, and I will always be grateful to Baylor."

Editor's Note: In this article, the quotes attributed to Rev. Robert L. Gilbert and others who are deceased are pulled from biographies and numerous publications about this influential man. One quote has been altered to use 'n*****'--a style practice commonly used today. We err on the side of current standards while understanding Rev. Gilbert probably would prefer the unaltered version as seen in his many reports of the event.