What's at Stake? Hobby Lobby and the future of religious liberty

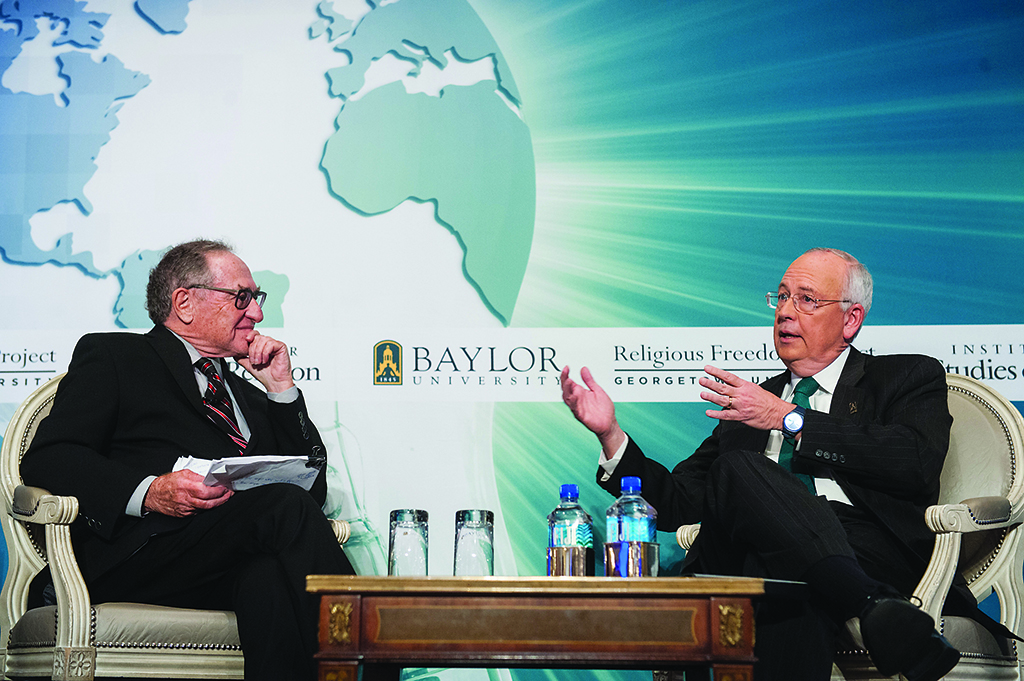

From humble beginnings in their 1970s Oklahoma City garage, David and Barbara Green launched what is now the nationwide commercial enterprise, Hobby Lobby. Their company—owned entirely by five members of the Green family—is at the epicenter of an important legal battle over the breathtaking reach of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). At issue is whether—due to the Greens’ deeply held religious objections—the Hobby Lobby owners have an enforceable freedom-of-conscience right not to provide several contraceptive methods (four out of the 20 ACA-required methods) to the company’s employees. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this closely watched case on March 25 and are expected to make a ruling in June. Baylor President and Chancellor Ken Starr and Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz sat down for a compelling conversation during a half-day conference titled “Everybody’s Business: The Legal, Economic, and Political Implications of Religious Freedom.” Held the day before Supreme Court oral arguments on the Hobby Lobby case, the conference was co-sponsored by Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion and Georgetown University’s Religious Freedom Project. Following is a condensed version of their conversation.

Starr: Briefly stated, the case that we argue tomorrow involving the Affordable Care Act’s implementing regulations with respect to contraception, involves a family. Yeah, it’s a corporation, it’s a for-profit corporation, so you’re going to read a lot and hear a lot about “Does the First Amendment really apply at all to corporations?” Well, OK, maybe they apply to nonprofit corporations, because churches and synagogues may incorporate as a nonprofit, but what about for-profit corporations?

Hobby Lobby is a great American story. David and Barbara Green in the 1970s had an idea, an arts and crafts store idea. And over the fullness of time and hard work—and they would say by God’s blessing, by Providence—but a whole lot of hard work and energy, now over 500 stores, and about 13,000 employees. The corporation is closely held … The family owns it, namely David and Barbara, and then the three adult children. That’s it. It’s a closely held corporation.

So one of the issues that is going to be in the case is, does the Affordable Care Act’s requiring company’s employees benefit plans to provide 20 forms of contraceptives—including four that the Green family, as a matter of conscience, object to on pro-life grounds. … Does the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), by its terms, provide an exemption for the Green family, doing business as Hobby Lobby?

So Alan, your thoughts?

Dershowitz: Well, first, that’s a very fair statement of the case. … I’ve been thinking about this subject now for 65 years. Let me explain why. When I was 10 years old, my father had a tiny little store on the lower east side of New York, where he sold men’s underwear and work clothes. He was a jobber—that is, he was the middle man. Never made much of a living, but was, and all of his life was, a very Orthodox Jew. And therefore, he couldn’t keep his little store open on Saturday, which is the Shabbat. In order to make a living, he had to open it on Sunday. Occasionally, I would go and help him on Sunday. And one day when I was there helping him on Sunday, the police came and arrested him for violating the Sunday closing law. They didn’t take him away; they just gave him a summons and told him he had to be in court in two days.

My father asked me to come out of school to watch how the American legal system operates. He was very lucky that day because the judge he drew was named Hyman Barshay, another Orthodox Jew.

So my father came before Judge Barshay, and Barshay said, “Why are you open on Sunday?” And he said, “Because I have to be closed on Saturday, because I’m an Orthodox Jew.” The judge said, “OK. What was the portion of the week that they read from the Bible in the synagogue on the Saturday before you weren’t able to close your store on Sunday?”

You know, in the Jewish tradition, every week you read from the Bible, and every biblical portion—we don’t do it by chapter—has a name; the name of one of the characters in the portion or the first word in the Bible. My father immediately knew the answer. The judge tore up the ticket, and said, “If you hadn’t known the answer, I would have doubled your fine.” [Laughter]. So much for separation of church and state and freedom of religion.

But I have been thinking about this subject, literally, since that period of time. Now, I am your perfect audience here. Why? I am a skeptic. I am a skeptic about everything. I am a skeptic about religion. I’m a skeptic about law. I’m a skeptic about science. I’m a skeptic about skepticism. …

And I’m skeptical about our abilities to achieve justice. I would, today, regard myself, as I said, as a skeptic, but tremendously respectful of religion. … I have told my students, if I were ever on a desert island and I could only bring one book with which to educate my students in philosophy, law, psychology, you name it, it would be the Bible. And by which I would include the Jewish Bible and the Christian Bible. If I had a third book, I would also include the Qur’an. I think you can learn so much from religion and religious traditions, even if one is a skeptic about some of the ultimate questions.

Now, I have to say I am not sympathetic to the views expressed by the wonderful Green family, whose business I love and whose story I love. I’m not sympathetic to your views on birth control. My views are completely different from yours. I believe birth control is a good thing for society. I believe that the right to control one’s procreative abilities are very important for society. I am also a big admirer of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act.

None of that is relevant to this discussion, because it’s not I who decides whether you have a religious right to do something that I disapprove of. It’s you who decides that, subject, obviously, to the Constitution and statutes. And the case is not about whether you like [ACA] or not; it’s whether or not the statutes in the penumbra of the Constitution require a religious exemption in cases such as yours.

So in the end, I’m waiting to be persuaded. I may end up persuaded that you’re right as a matter of statutory interpretation and as a matter of kind of constitutional overlay. I may regret that result from a policy point of view. Anything that hurts affordable care, anything that sets back a woman’s right to choose contraception—and I know you’re not suggesting you’re opposed. In fact, it’s a very interesting brief and a very interesting way you put it. You have no opposition to individuals disagreeing with you about using contraception; you just can’t, as religious people, who feel that this is in violation of the right to life, you can’t participate.

Starr: In those four, out of 20. Let’s just be clear.

Dershowitz: In those four.

Starr: It’s the principle.

Dershowitz: It’s the principle that really matters, and I’m completely supportive of you on the principle.

I just want to say one word about the jurisprudence before we have the discussion. I had a great time reading the briefs in this case, and it really reminded me of being back in my Jewish parochial school reading the Talmud. On the one hand, on the other hand. You read this case, there is this interpretation of this case.

There is the old story of the Eastern European rabbi, and he is sitting in a divorce court. The wife comes in and says, “My husband is a bum. He’s a drunk, and he beats me.” And the rabbi says, “My daughter, you’re right.” And then the husband comes in and says, “My wife, she’s lazy. She doesn’t do anything. She doesn’t work. She doesn’t take care of the children.” And the rabbi said, “My son, you’re right.” And the student says, “Rabbi, they both can’t be right.” And the rabbi says, “My son, you’re right.” [Audience laughter.]

And so that’s the way I felt reading the briefs, because the discussion is so Socratic. It’s so Talmudic. You can interpret the constitutional jurisprudence today almost any way you want. … When you read these briefs, the jurisprudence of freedom of speech, the jurisprudence of how you reconcile the free exercise clause with the establishment clause, with the general presumption in favor of governmental regulations, is so obscure and so difficult that no one can predict the outcome of this case with any certainty. I can predict one outcome.

Starr: What is that?

Dershowitz: I will predict that no intelligent, reasonable person will want to distinguish between a business owned by an individual, and a business which has become an S corporation [term describing a corporate structure that qualifies for Subchapter S of the Internal Revenue Code]. I find that to be an absurd argument being made by the government. I thought the government’s brief on that issue was trivial and silly. For me, the issue of whether you can do it through a corporation or individually is a religious issue.

If your religion tells you that creating a corporation won’t allow you to circumvent your general religious obligations, you’re bound by that. In fact, yesterday I called a good friend of mine, who is a very distinguished rabbi, and I asked him the following question.

I said, “What if I own a store, and I want to open it on the Sabbath. I’m not allowed, as a Jew, to open my store on the Sabbath; what if I become an S corporation and decide that the S corporation will open the store on the Sabbath?” He said, “Don’t be ridiculous. You can’t do that. You are the corporation, and the corporation is you. That’s a religious principle.”

And it seems to me, if the court were to, in any way, try to undercut that religious principle by citing state law of what a corporation is, or Blackstone as to what a corporation is, they would be falling into the trap of themselves violating the free exercise of religion clause. After that, I have some more difficulties, which let’s discuss.

Starr: Let me begin the story with a case that your father would really relate to: Braunfeld v. Brown, a Warren court decision that held that Abraham Braunfeld could be held criminally liable, as an Orthodox Jew, for keeping his store open on Sunday. … And here’s the key: It does not create an exemption for Orthodox Jews. You just have to close. And so Abraham Braunfeld, who owned a store, along with other Orthodox Jews, said this really imperils our wherewithal. It’s not just reducing our profitability. The competition is open on Saturday, so we need to be able to do this.

The Supreme Court, speaking through the voice of Chief Justice Earl Warren, ordinarily a friend of liberty, said, “Listen, this is up to the legislature. If you want a religious exemption, go to Harrisburg and do your best. But we’re not going to interfere with the judgment of the legislature.”

Two years go by, Alan, and then a subsequent case called Sherbert v. Verner involves a Seventh-day Adventist, who cannot work on her Sabbath. She is told by her employer, a textile mill in South Carolina, “Listen, you have to work on Saturday, or you’re out of here.” And she eventually said, “I guess I’m out of here.”

She sought unemployment compensation; the state of South Carolina denied it. It ultimately goes up to Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court said that because she is essentially being penalized for the exercise of her religious practice—she is not prevented from going to church or her expression, but this practice of hers, namely to honor the Sabbath by not working, is being infringed by the state—the state must come forward with a compelling reason, a justification of the highest order, in order to overcome that claim of religious liberty. The state came up, “Well, we’re worried the people will be malingers. They’ll pretend they’re religious. It’ll be bad for our economy.” Whatever the arguments were, they were considered by a super majority of the Supreme Court, an utter makeweight.

And so the Supreme Court, speaking through the voice of William Brennan, two years after Braunfeld v. Brown, upheld that claim of religious liberty. Alan, something happened at the Supreme Court, because a very persuasive justice named William J. Brennan, who had been in dissent in the Braunfeld case, was now writing the majority opinion for the Warren court.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act reached back into time and said “We liked the Warren court’s approach.” The House of Representatives unanimously passed RFRA. The Senate passed it 97 to 3. President Clinton signed it into law during his first year in office in November of 1993. … And President Clinton, signing this measure into law, talked eloquently about how religious freedom is our first freedom. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act is meant to protect us as individuals, including S corporations. Alan, reflections on what I just call RFRA’s journey?

Dershowitz: Well, I actually worked on drafting some of the language of the Religious Restoration Act, and I very, very strongly support it. One of the cases that led to it was also the case of a Jewish psychologist, who had testified wearing a kippah, and had been told he couldn’t wear the kippah. And the Supreme Court, in an opinion by Chief Justice Rehnquist, affirmed that.

So this was a situation where many in the Jewish community, many in many Christian communities, and many other communities, all got together. And the beauty of the act, and the beauty of some of the court decisions that come afterward, is that they really do focus on minority religions—the Hialeah case, where you have a very obscure religion where they sacrifice chickens; the Amish cases, and other cases. These are not majority religions, and so there really is no conflict in those cases at all between the fear of establishment and the free exercise. …

When it comes to issues like whether or not an S corporation, a family-owned corporation in a wonderful business, should be allowed to be exempted from providing a service that perhaps many of the employees would benefit from and would use, I think that’s a much more complicated and difficult question.

I would look for a middle ground. I would look for a way of finding a way to not ask the Green family, or any other family, to compromise their religious view. But there are a few principles that have to be in operation.

Number one: Nobody should ever profit financially from being accommodated. That is, if you’re accommodated, you shouldn’t benefit. You shouldn’t gain any financial benefit from that. So there has to be a way of making you pay what you would pay, but for your religious views, but in a way that’s consistent with your religious views. And that is a kind of accommodation that I think makes a lot of sense.

Now, the next question is: Should you ever have to pay to exercise your religious views? That’s a complicated question. We all know, whether you read about the life of Jesus or the life of other religious leaders, that it’s not easy to be religious. It’s not easy to be a person of God, and it’s not inexpensive either. For most of my life, I ate only kosher food. Kosher food was 20 percent more expensive than non-kosher food. We regarded it as a kosher tax; it was worth paying because wanted to eat kosher. I would never dream of asking the government to subsidize that 20 percent. …

Again, I think what we need to do is search for accommodation at every stage. Try to figure out ways of not requiring you to compromise at all with your religious views, but making sure that it also doesn’t hurt those whose religious views are different from yours. I want to make sure that your 13,000 employees, or however many of them are women who would take advantage of the four types of contraceptive devices, aren’t in any way disadvantaged by the exercise of your religious views.

I am confident this can be achieved. I think it would be useful to try to find middle ways. I don’t like to see conflicts between a religion and governance. They are very dangerous, historically. It’s far better if we can find methods by which we can work out these accommodations.

…

Starr: We have, among other very distinguished guests here, Os Guinness, a wonderful commentator on the culture, including globally. And Os asked a question in one of his recent books, The Global Public Square, “How can we live together with our deepest differences?”

And in The Culture of Disbelief, and your colleague for a few years, Noah Feldman, in his book Divided by God, there’s this search, this eagerness, to find how can we, given our diversity—culturally, religiously and so forth—live together peacefully, and resolve our differences peacefully, not by going to litigation, but just culturally?

I think there is a growing sense that if you are a person of deep religious faith, you’re in the crosshairs now. There are people here from different religious communities who feel genuinely embattled in terms of freedom of conscience. And so what I want to now lift up in terms of the culture, what I think the Supreme Court did on a great iconic case called West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, is to say the government cannot interfere with your freedom of belief. “That if there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” the great words of Robert Jackson, “it is that no official, high or petty, can determine what is orthodox in matters of,” including obviously religion, but including politics and the like.

That is so bedrock, I think, in the American culture, but increasingly, people of faith are saying, “I’m not so sure that West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette is in the culture anymore.” … What’s your sense of that?

Dershowitz: I’m going to now point my finger at you. And I’m going to say it’s your fault. You haven’t done a good enough job, in the marketplace of ideas, to persuade Americans of your point of view. I agree with you. I think you’re losing the battle among young people. If you look at what’s going on in many colleges and universities, there is increasing disdain for religion. I don’t like it. I don’t like it. I find America to be the best country in the world in terms of not having these divisions. For example, the two countries I know best are the United States and Israel. And Israel is having a terrible problem, because if you’re not very religious in Israel, you’re anti-religious. And the reason for that, I believe, is because the state has played too great a role in promoting religion.

Separation of church and state is good for religion. … Jefferson said that. … It’s very, very important. And in this country, nobody can tell me what I have to do and don’t have to do. I love religion. I love religions that I’m not part of. I admire it. I read religious books. I listen to the radio show Religion on the Line. I’m involved in religion in many, many ways.

If I lived in a country where they told me what religion I had to practice and how I would have to practice it, I’d be religion’s worst enemy. I would be fighting it tooth and nail. And I want to keep it that way. So my view is, don’t ask for the help of government. Don’t ask for the help of the state. Do a better job. Go out there and make religion more relevant to the life of young people. Don’t create conflicts between the rights of women and the rights of religion, between the rights of gays and the rights of religion, between the rights of other dissenters and the rights of religion.

You are going to lose many of those battles, unfortunately. You have to figure out a way—and it’s your job—you have to figure out a way of making people love what you believe in and love what you’re doing.

…

Starr: Let me pick up on your comments in terms of certain issues: gay and lesbian rights, reproductive freedom, what many view as the taking of human life… Is there, in your view, I don’t want to call it middle ground, but is there cultural room for us, is there a corridor, that we can all say, yes, we’re comfortable in the corridor even with our disagreements, as long as we respect freedom of conscience?

Let’s just use the example of Catholic hospitals or Orthodox Jewish doctors declining to perform certain kinds of procedures. Now, that interferes with reproduction freedom, and you feel very strongly about that, but what do we do with that situation in terms of the role of the state? Should the state be able to command an OB/GYN, “You must participate in a procedure that utterly offends your conscience?” Should the federal government be able to do that?

Dershowitz: No. I think the answer is no, except if the person is an emergency ward doctor and somebody comes in, in an emergency, and there is no realistic alternative.

As a general rule, there should be that kind of accommodation. Now, let’s move to another area. What if a person—there are these cases now pending in the west of the United States—what if a person says, “I’m so offended by the gay lifestyle that my religion precludes me from delivering flowers to a gay wedding?” …

My gut tells me there is a big difference between making a doctor perform an abortion, which I would never think would be ever proper under any circumstances, except, as I said, in the emergency situation, and requiring somebody not to discriminate against a gay person, or not to discriminate against an atheist or somebody else who offends them deeply to their religious core.

Starr: And then what about an Orthodox Jewish rabbi or an evangelical minister/pastor, or Catholic priest, who cannot, in conscience, even though there is the law of the state where the person is serving in ministry, cannot in fact perform, in conscience, a same-sex marriage?

Dershowitz: Oh, I think that clearly nobody should be required to perform a same-sex marriage. Marriage, today, is a religious phenomenon. I mean, my own view, I would like to see the state get out of the marriage business. The state is not in the baptism business. It’s not in the circumcision business. It shouldn’t be in the marriage business. Marriage is a sacrament, and sacraments should be performed in church. [Audience applause.]

My view is that everybody should be able to get a civil union, which obliges you to do certain things that you are responsible for, and gives you certain tax benefits and disadvantages, and [gives] the state benefits and disadvantages. Everybody should be able to sign up for that, and then the vast majority of us would then go to our church, our synagogue, our mosque, and have a rabbi, minister, an imam, perform the religious part of it.

And of course nobody, no religious person, should ever be required to perform a marriage that is against his or her religious views. I would be categorical about that. On the other hand, a person shouldn’t go and become a clerk in city hall if he knows that he couldn’t marry two men who were gay, or a Jewish man to a non-

Jewish woman.

Today, an Orthodox rabbi is forbidden from marrying a Jew to a non-Jew, but obviously a civil clerk can’t refuse to do that. And if the civil clerk is an Orthodox Jew who says it’s against my conscience, the answer is get another job. You shouldn’t be a clerk, whose job it is to have to marry people regardless of religion.

Now, of course, they’re going to argue tomorrow, “Get another job,” to you. They’re gonna argue, the Constitution doesn’t give you the right to be a corporation. It only gives you the right to exercise your freedom of speech. There is no religious right to be a corporation. So you can easily have your religious rights, just stop being a corporation. I hope that argument loses, because to be a corporation gives you significant economic benefits, which would be denied you if you were forbidden from doing that. And I don’t think that’s an appropriate accommodation. That’s too great an accommodation.

On the other hand, if you get any financial advantage from being able to opt out of the providing of these four different contraceptive or abortion devices, you should have to pay a tax, a general tax equivalent to the money you’ve saved so that you don’t end up profiting from the accommodation of your religious views. It seems to me that’s a fair accommodation.

…

Dershowitz: Why doesn’t Congress solve this problem? Congress could do it very simply, could simply say today, when you get back to work this afternoon, Congress could probably pass unanimously a resolution saying, “S corporations are people for purposes of the Religious Restoration Act,” and problem solved.

Starr: That is one of the odd things … If Hobby Lobby loses, then it’s a setback, obviously, I think hugely so for religious liberty, but it’s really the lawyers relief act, because businesses will simply say, “All right. What’s the nature of my partnership? Can I have a limited liability partnership and the like?” So it will be a great day for the corporate lawyers. Because you can, in fact, manage around it.

I’m not saying it’s easy to take a corporation of the size of Hobby Lobby and then just say, OK, we are now filing the articles of dissolution and the like, but it can be done. Corporations can dissolve. And so it’s part of the oddity of this entire argument on the part of the government that, because it’s a for-profit corporation. … So think of it. If they had remained as five partners in the family, they’d have full protection. So at what moment did the magic occur? Poof, you had religious liberty rights, and now you don’t. …

Dershowitz: Your accountant took it away from you. [Audience laughter.]

Starr: And it is an exercise, as we say in the law, an exercise in formalism, which is the kind of exercise that gives lawyers a bad name.

Dershowitz: Absolutely.