Dynamic Duo

It's a long way from Waco to Hollywood—in more ways than one. Many Baylor alums have found a way to bridge the physical and cultural gap between Central Texas and the California city that serves as the center of the entertainment universe, and thus inspire the next generation of Baylor storytellers in the process. Along the way, they have found that breaking in requires skill and inner drive plus a touch of good fortune that far exceeds most of their contemporaries.

For those who do break into the entertainment industry, the demands of writing a television show or selling that next film script can quickly become all-encompassing—which made it all the more amazing in February when students in Baylor Film and Digital Media (FDM) Advanced Screenwriting course found themselves in the presence of the writer and executive producer of not one, but two current hit television shows.

It's also a long way from Chicago, the production locale of those two shows, back to Waco. Yet, there was Derek Haas, BA '91, MA '95, in a Castellaw Communications Center classroom, taking a break from the NBC shows Chicago Fire and its spinoff, Chicago P.D., answering student questions about breaking into the industry and offering his honest assessments as the students nervously pitched him the scripts they were writing.

To people who know Haas and his writing partner, Michael Brandt, BBA '91, MA '94, it isn't surprising Haas made the trip. Amidst the rigors of life in film and television, Haas and Brandt have a reputation for being there for Baylor whenever a student wants to meet or whenever FDM could use their help.

Advice from the duo shaped the setup of the Advanced Screenwriting course to better prepare Baylor FDM students for the industry upon graduation. The opportunities they have given to Baylor students have led to greater numbers of Bears working in Hollywood, and their willingness to help out their alma mater in a number of settings has kept them closely connected to campus and FDM. If more proof of their love for Baylor is needed, watch a few minutes of their work and discover a character named after a Baylor professor or building.

I was unsure of where I was going to go in life," Brandt said, "and I found a place in the Baylor communications department. I'm loyal to where I came from, and we're loyal to Baylor."

Their highly successful partnership, formed on the Baylor campus, has produced two television shows, five feature films, a television movie and a video game. The duo has displayed their versatility by creating characters ranging from ranchers to street racers, in settings from the Old West to the streets of the Chicago, on both the big and small screen.

"I don't know why the two of us got stuck together and have done this for more than 20 years," Haas reflected, "but I think more than anything, it was common interests, common goals and seeing the talent in each other."

Both Brandt and Haas state they are better working together than they are as individuals. While it seems typical that such partnerships dissolve for a variety of reasons, their alliance has taken on the quality of iron sharpening iron. However, the working relationship they forged as Baylor students began somewhat improbably. That they met in a screenwriting class seems conventional enough, but neither one traveled a direct route to cinematic success. Haas, a journalism and English major, took plenty of film classes but dreamed of writing the great American novel. Brandt, a business major, thought he wanted to go into media but had little direction beyond that broad notion.

"I graduated from the business school where I was totally misplaced," Brandt reflected. "I had no idea when I first started what I wanted to do. Throughout my senior year, I watched my friends go through the interview process and get offered jobs in accounting firms, financial firms or banks and making lots of money. And here I was, unsure of where to go, and I had to resist the temptation to just settle for a job."

Fortunately for Brandt, the seeds for a career in production had slowly been developing. He took a few electives in what was then called the telecommunications division (now FDM) in Baylor's College of Arts and Sciences, and he interned at a production company in his native Kansas City. After an epiphany that he wanted to create more lasting forms of media, such as movies, he signed up for a screenwriting class, where he connected with Haas.

Bob Darden, BSEd '76, taught the class, and Brandt and Haas quickly excelled.

"Within 20 pages of their submissions, I knew," said Darden, now an associate professor in the journalism, public relations and new media department. "My job was not to get in their way. Their stuff was so polished, and it was something they clearly wanted to do."

Brandt and Haas already knew each other—both were members of the same fraternity, Sigma Alpha Epsilon—but they had no idea that they shared so much in common until that class.

"I think from the get-go that we had the same sensibilities," Haas said. "We thought the same things were funny. We liked the same movies. We both liked sports and talking about the same topics—so it wasn't like 'Mutt and Jeff' coming together. We saw we were like-minded."

Haas' path wasn't quite as circuitous as Brandt's since the screenwriting class was in the English department. Yet, it was that class and Darden's influence that moved Haas to strongly consider his possibilities and options.

"You talk about someone who changed your life—that's Bob Darden," Haas raved. "He was so charismatic and enthusiastic and cynical, yet he talked to us as adults."

So profound was this class on their lives that Brandt and Haas have created a tribute to honor the professor: They kill a character named Darden in every one of their productions that includes a death.

It would still be a long way from that seminal screenwriting class to Hollywood. Haas went on to graduate school, and Brandt realized that could be a path for him, too.

"After graduation, I went in and had a conversation with Dr. (Michael) Korpi, who I didn't know very well because I'd been in the business school," Brandt said. "I tried to convince him and Corey Carbonara that even though I was a business major, I knew what I was doing in production. So, it was kind of a pivotal moment for me, because what I was asking from them was a teaching assistant position."

Without dreaming of the future successes that would develop from their faith, Dr. Korpi, FDM professor and former chair of the department, and Dr. Carbonara, FDM associate professor, took a chance on the business major and were willing to make the investment in Brandt. At the same time, Haas was taking graduate courses in the English department and honing skills that would prove complementary to those Brandt was developing in production.

Another pivotal moment would come through the most basic of questions. Korpi one day asked Brandt what he wanted to do after graduation. Brandt responded that he wanted to write and direct movies, and Korpi's practical response changed the trajectory of Brandt's life.

"Korpi said, 'Well, then you should learn how to edit. Best-case scenario, you become a better storyteller. Worst-case scenario, these new machines will be in Hollywood, and you will be a guy who knows how to run one,'" Brandt recalled.

That simple conversation would prove to fast-track Brandt to Hollywood where, seven years later, Haas would join him.

Non-linear editing was beginning to take root in Hollywood as Brandt and Haas pursued their graduate degrees. Non-linear editing was a game-changer because film no longer needed to be physically cut. Productions could be shaped on hard drives or video servers much more quickly and easily. Baylor FDM was at the forefront of that technology. Brandt as a student in Waco was learning the next big thing in Hollywood, before the big names in Hollywood had fully grasped it themselves. That expertise in a cutting-edge technology would prove to be a very marketable skill indeed, connecting him with such directors as Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino.

"It was the beginning of something new, and Baylor was tuned into it so early that it allowed me to be one of the first people in on it," Brandt said. "And here I was, a guy who knew the technology well. Corey and Korpi both instilled in me the idea of what the next wave would be."

Dr. Korpi's advice proved true. Brandt's technical ability got him in the door and enabled the two to pursue their artistic dreams. His connections would bloom. A script written by Brandt and Haas was eventually purchased. While that script, "The Courier," was never produced, the fact that it was purchased convinced Haas to move to Los Angeles and pursue the dream with vigor. Screenwriting success came slowly at first, but the rest has been history. Their first screenplay that became a feature film, 2 Fast 2 Furious, came in 2003. Catch That Kid, 3:10 To Yuma, Wanted and The Double followed. Now, with Chicago Fire and Chicago P.D., the duo has taken their talents to television and started a new chapter in their career.

How have the two Baylor graduates managed to keep their partnership intact for more than 20 years, all the while navigating the roller-coaster ride of Hollywood failures and successes?

"Michael describes it well," Haas said. "I like to paint, and Michael likes to sculpt. I love the blank page, the blank canvas; whereas, Michael has more of a problem starting off with nothing, but he's great with my script in his hands. I love to fill it up, and I typically do what we call the vomit draft where I don't look backward and I don't care if it makes sense. I don't have to worry because I know he's coming in, and he may rewrite half the script. Out of this block of concrete I write, he's going to put a face on it, and we may pass it back and forth several times before anyone even sees it."

With their lives revolving around the tight time schedule of a weekly television show, that setup continues. Both are writers and executive producers of the shows they develop and co-create, but they don't share an office. They email scripts back and forth until the finished product emerges, just as they have done since those early days at Baylor when they realized they thought the same stories were cool.

Haas explained, "When we started writing together, we realized we were writing to impress the other person. And, we never had egos. I think the ability to have that first pass be us rewriting ourselves broke us in more. We were able to take notes from other people because we were already doing it ourselves."

Their openness to script changes and a reputation for being nice guys in a place like Hollywood helped them advance in the industry, despite what they recognize as uncertainty about the way the industry worked when they arrived. It is that uncertainty that they're trying to help Baylor FDM eliminate in the students they graduate. And, it is that willingness to help current Baylor students that brings their relationship with their alma mater full-circle.

Back in the Baylor FDM Advanced Screenwriting class, Haas is listening to every story idea that students have time to pitch to him on that February day. Deep Focus, a showcase highlighting student work and raising money for FDM, takes place the next night in Dallas, and Haas participates in that, too. Brandt would have been there as well, but a last-minute schedule conflict kept him away. Their willingness to share their time is incredibly meaningful to not only those students, but to FDM professors who know the duo brings a certain experience factor that only someone in the business can provide.

"They really go above and beyond in always being available to help our students and help us know what's happening in Hollywood," said Dr. Chris Hansen, director of the Film and Digital Media division. "I emailed Michael and Derek and said, 'We'd love for you to come speak and take part in Deep Focus,' not really thinking they would have the time. And they both emailed me back and said they'd be here. Honestly, they love giving back."

Giving back for Brandt and Haas goes far beyond finances. For instance, the genesis for the FDM Producing for Hollywood class now offered each fall developed from a meeting in California four years ago. Hansen, Carbonara, Korpi and Senior Lecturer Brian Elliott met with the pair and other prominent Baylor alumni in Hollywood to ask what FDM needed to be doing to better prepare their graduates for a career in entertainment.

"I came back from that meeting saying, 'We have to engage these guys more,'" Elliott said. "I asked Chris Hansen if I could teach a class in producing—talking about things like how to get a job, how do you interact with L.A., and how does this world out there work? Because one of the main things they told us is that nobody taught them the business of survival out there and how to navigate."

Following the recommendations of Haas, Brandt and others, the producing for Hollywood course now prepares students in part by bringing in speakers, such as Haas, other alumni and leaders in the business, to provide students with frank, real-world advice on breaking into the industry. The course helps students to gain a better understanding of the business aspects and builds upon other FDM classes that equip students with technical training and storytelling skills.

Numerous students and graduates have benefitted from the duo's willingness to provide opportunities for their Baylor compatriots. Among those is Rachel Armstrong, BA '13, who asked to meet with them while she was visiting the West Coast and landed a job as an assistant to Haas.

"Certainly loyalty plays a big part of it. But it shouldn't go overlooked that every time we have given chances to Baylor students, those students have come through for us 100 percent of the time," Brandt said. "We see the fruits of that relationship. It's a two-way street. It's not just us giving back, but we're also getting something out of what Baylor FDM has to offer—its students."

Haas added, "Baylor was such an instrumental part of my career. I met my wife (Kristi, BA '93) and writing partner on campus, and it fostered a love of writing and film. Giving back—it was never a question."

Haas also feels a responsibility to give plainspoken, direct advice on what the department needs to do so that it continues to graduate students who can be competitive with those from film schools in California. He once bluntly told FDM that professors needed to be harder on the students who have dreams of making it to Hollywood. That advice may seem unpleasant, but it's helped more graduates advance in the business.

"Baylor's not a USC or one of those California schools whose graduates are ubiquitous in L.A.," Hansen said. "Derek and Michael have pride in Baylor people doing well out there. So they spend time talking to us about opportunities and about our strategy and curriculum. They're always willing to talk when we want to engage them, and of course, we always do. It's hard to quantify just how valuable their assistance is for our department and our students."

When watching Chicago Fire or Chicago P.D. or one of their movies, listen for characters with names like Neff, Browning, Penland and Hankamer, and, of course, be prepared for a Darden to die. As much as those names mean something to the Baylor family, they are symbols that two prominent alums haven't forgotten their alma mater. Those fictional characters are gentle nods that Michael Brandt and Derek Haas are thinking about ways to help the next generation of Baylor filmmakers to tell their stories. In the process, those Baylor graduates bring a quality to Hollywood the industry needs—a quality that, when applied with skill and ability, speaks volumes about the Baylor mission.

"Baylor just graduates kids with a certain sensibility that is possibly gentler and for lack of a better word, nicer," Haas said. "In the creative business, there's this romanticism of troubled, tortured artists, but you don't have to be like that. I think that darkness, for lack of a better word, wasn't innate in Michael and me, and certainly not in filmmakers like John Lee Hancock or Geoff Moore [BA '98, writer and director of Better Living Through Chemistry]. So did that come from Baylor? It had to."

The word "cutting edge" can be a rather abstract concept. But if you have dreams of a career in Hollywood, you know the cutting edge is precisely where you want to be. That's just one of the many reasons aspiring filmmakers choose Baylor Film and Digital Media (FDM). Baylor FDM's reputation for excellence attracts students to Baylor—and it also attracts resources to give students an advantage in the market.

Baylor FDM was chosen by Microsoft, and digital cinema software company ASSIMILATE, Inc., to receive technology that will equip FDM students to use tools that many Hollywood veterans are only beginning to utilize. ASSIMILATE gave Baylor 100 licenses of Scratch®, a postproduction software that allows filmmakers to process every stage of the production as it takes place. Microsoft added its latest generation tablet to the mix so that filmmaking students have the technology needed to maximize the functionality of the software. These gifts represent a $500,000 investment in Baylor FDM.

"One of the reasons we were selected was that ASSIMILATE looked at us and really saw the depth of our program," Dr. Corey Carbonara, FDM Professor, said. "We're recognized because our alums are doing great stuff in the industry and because our program constantly equips students in every aspect of the industry. And they have reached out to us and said, 'we want to partner with you'—organizations like ASSIMILATE, that led to Microsoft, that is leading to other things that have us very excited about the future."

These relationships will allow Baylor FDM graduates to make an immediate impact in the entertainment industry—filmmakers with a cutting edge aptitude and a calling that sees beyond the ratings or box office figures.

You can also support the Film and Digital Media Fund for Creative Excellence which covers costs for productions, additional equipment, speakers and more. To learn more, visit baylor.edu/fdm or contact Rose Youngblood at (254) 710-2561.

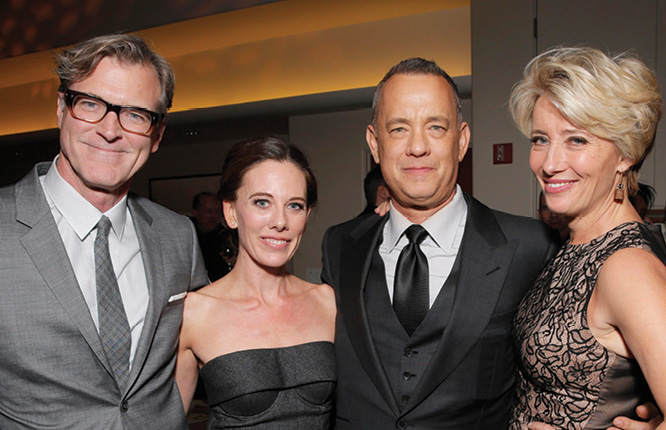

Director John Lee Hancock, writer Kelly Marcel, actors Tom Hanks and Emma Thompson attend the after party for the U.S. premiere of Saving Mr. Banks. (Photo by Todd Williamson/Invision/AP)

Bears in the biz

John Lee Hancock, BA '79, JD '82, and Kevin Reynolds, BA '74, JD '76, are two more examples of Baylor alumni who have found great success in Hollywood.

Hancock recently directed Saving Mr. Banks, which marked his first time back in the director's chair since The Blind Side, which earned a best picture Oscar nomination in 2010. He both wrote and directed The Blind Side; he has also written such films as A Perfect World and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, and directed movies such as The Rookie and The Alamo. Hancock's upcoming projects include the May 30 release of Disney's Maleficent starring Angelina Jolie (co-writer) and The American Can (screenplay), which tells the story of a New Orleans native and combat Marine who rescues 244 people trapped in an apartment building in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Will Smith will star as John Keller in this 2015 release.

Reynolds has directed a number of hits, including the miniseries Hatfields & McCoys, the most-watched scripted entertainment program in cable TV history with 14.3 million viewers for the finale. He wrote the screenplay for Red Dawn (1984) and directed films such as Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Waterworld, The Count of Monte Cristo, and Tristan + Isolde. He is director of the upcoming film, Resurrection, which is in pre-production and expected to be released in 2015. The story, told from the perspective of an agnostic Roman Centurion, covers the first 40 days after the resurrection of Jesus.