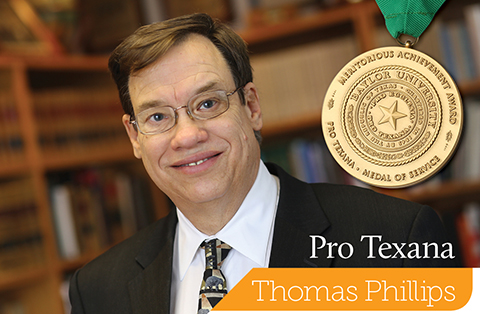

Pro Texana Medal of Service, Thomas Phillips

Former Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Tom Phillips, BA '75, has made a career of making good decisions. Besides choosing to attend Baylor over Texas A&M, earning a Harvard Law degree, marrying the daughter of two Baylor grads, helping streamline case processing in the Harris County civil district courts, and leading a reform movement at the state level, he also took the initiative to ask Ken Starr if he'd be interested in becoming Baylor's 14th president. That's not a bad record.

At Baylor, the Dallas native says joining Circle K (now ATO) and being a charter member of Student Foundation helped him come out of his shell a bit. He majored in political science and particularly enjoyed his courses with Robert Miller and Al Newman.

After Baylor, Phillips headed to Harvard Law School, where he began to appreciate the well-rounded education he received at Baylor.

"Since law intersects with so many areas of human activity, a little knowledge about a lot of things can be very helpful to a lawyer," he says.

After Harvard, Phillips served as a judicial clerk, which sparked his ambition to be a judge. After six years of law practice in Houston, Gov. Bill Clements appointed Phillips to be judge of a newly created civil district court in Harris County in 1981. There he helped lead a movement to streamline the disposition of cases by abolishing the "central trial docket" and requiring one judge to handle an entire case from filing until final trial court judgment.

"It was taking up to three or four years to dispose of simple dispute, which was both stressful and expensive for the litigants," says Phillips. Within a few years the number of pending cases per judge had shrunk by more than half.

As a district judge, Philips had become very frustrated with the conduct and the decisions of the Texas Supreme Court, which was under severe public criticism. He decided he wanted to serve on the court. At the time, no Republican had won a statewide race below the office of governor or senator in Texas history. The state's Supreme Court didn't seem a very likely place to break that record.

"Even if I couldn't win, I decided that running would let me talk about why fair and impartial courts were crucial to our society of ordered liberty. I thought I could win support from the press and from a diverse array of professional and civic associations, and maybe running a strong race would lead to something good."

Before Phillips could announce his intentions, John Hill abruptly resigned as Chief Justice, leaving the top spot in the state judicial system vacant, so Phillips applied to be appointed Chief Justice. He ultimately was one of six finalists to be interviewed by Gov. Clements, and Phillips was appointed. Since the remaining term was brief, Phillips immediately had to apply to run for the court again. He won.

Before Phillips could take office, public criticism of the Texas Supreme Court was ratcheted to new levels. 60 Minutes ran a segment on the Court titled "Justice for Sale?" alleging that large campaign contributions and personal favors from some of the state's top attorneys to some of the sitting justices had tainted the Court's decisions.

"Overnight, I went from being one of 400 district judges in the state to being the youngest chief justice in the nation," Phillips says. "It was a unique experience for my wife and me to be at the center of a public movement that was so much more important than our mere personal circumstances. The Baylor community was really wonderful throughout the campaign; I rode in the Homecoming Parade and had several great events in Waco."

By the beginning of 1989, four other new justices, Republicans Nathan Hecht and Eugene Cook and Democrats Lloyd Doggett and Jack Hightower (also a Baylor alum), joined Phillips on the Court. The new Court, Phillips contends, was "more balanced and scholarly. No one liked all of our decisions, and we surely made mistakes, but I think the majority opinions did a better job of explaining the legal reasons for the decisions that were reached."

Phillips was re-elected to a full six-year term on the Court in 1990. He won again in 1996 and 2002. "By the late 1990s, the justices of the Court were again virtually anonymous, which is how it should be if the court system is functioning well," Phillips observes.

During Phillips' time as Texas Chief Justice, he served by appointment from U.S. Chief Justice William Rehnquist on the Federal-State Relations Committee of the Judicial Conference of the United States, and he was elected by his peers to be president of the National Conference of Chief Justices.

In 2004, after failing to convince the legislature to propose a constitutional amendment to replace partisan, contested judicial elections with initial appointments followed by periodic "yes/no" retention elections for all judges, Phillips resigned from the Court. After teaching for a year at the South Texas College of Law in Houston and the Dedman School of Law at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, he returned to private law practice, joining the firm of Baker Botts L.L.P. in Austin. He primarily works on appeals of civil cases, but he also appears in trial courts and sits on arbitration panels and mediates disputes. "It is fascinating to be on the 'receiving end' of the judicial system," Phillips observed, noting that he sees now more clearly than ever why "it is critical for the rule of law for judges to be, and to be seen as being, absolutely fair and impartial. The great American contribution to governmental theory was separating judicial power from executive or legislative control, and making the judiciary co-equal to the representative branches. Perhaps the greatest benefit that our country can offer to those who choose to live or work here is a court system that enforces agreements and resolves disputes based solely on what the law commands, not based on the status or influence of either side. We must do everything within our power to safeguard the integrity and reputation of our judiciary."

Among his numerous honors, Phillips has been given the Baylor Distinguished Alumnus Award (1998) and the Price Daniel Public Service Award from Baylor (2004). He was also a member of the Sesquicentennial Committee of 150 in 1992-93 and the Baylor Presidential Search Advisory Committee in 2009-10. The majority of the Baylor faithful would likely agree that Phillips' contribution there proved fruitful -- he solicited Ken Starr to come to Baylor.

"Ken's combination of integrity, spirituality and professional success reminded me of the backgrounds that such giants as Pat Neff and Abner McCall brought to the Baylor presidency," says Phillips. Like Gov. Neff, he had served successfully in several diverse public offices -- in Starr's case, Assistant Attorney General, Court of Appeals judge, Solicitor General and Special Prosecutor. Like Judge McCall, he had a proven record in academia, having dramatically increased the prestige and visibility of Pepperdine Law School during his five years as dean.

"Third, and most critically, I thought Baylor had to have a president that was both deeply grounded in his own faith and sufficiently sophisticated to understand the recent theological and philosophical differences among Baptists and alumni groups without having been a party to any of the disputes. Throughout the months I served on the Presidential Search Advisory Committee, he just kept coming into my mind as the ideal candidate."

In 2010, Phillips was in Washington, D.C., on business and decided to attend a program at which Starr was speaking.

"I was hoping to have a chance to visit with him, but I still wasn't sure whether to broach the subject of the Baylor presidency. But when Ken walked into the room, everybody, regardless of their political leanings, rushed up to him and hugged him like a long-lost brother. I thought, 'If Ken Starr can draw that type of allegiance and friendship from such a diverse range of lawyers and judges, maybe he can bridge the competing visions for Baylor.'

"So I approached him and asked him about the possibility, and you know the rest of the story.

"I think this one five-minute conversation was the greatest contribution that I could ever make to our beloved university. So I can just ignore all those solicitations for monetary gifts," quips Phillips.

Phillips is married to Dr. Lyn B. Phillips (Alumna by Choice), and has a son, Daniel, a stepson, Thomas Kirkham, and three grandchildren.