Making the Grade

Baylor's school of education became one of the university's original six colleges almost 100 years ago, in 1919. Today, the school awards an average of 200 undergraduate and 100 graduate degrees annually and is comprised of four departments: curriculum and instruction; health, human performance and recreation; educational psychology; and educational administration. // School of Ed graduates utilize their degrees to impact virtually every aspect of the world of education. The six diverse educators profiled here range from a no-nonsense classroom teacher to an innovative superintendent of schools -- and from a publisher of educational materials to a Thai exchange student who established a university modeled after Baylor in his homeland.

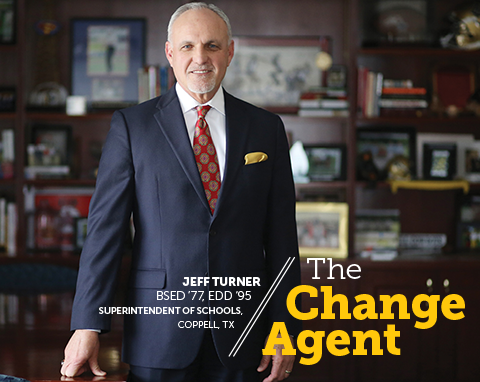

As a member of Grant Teaff's inaugural football recruiting class, Jeff Turner began his college career with one of the most inspirational coaches and teachers of the 20th century. While Teaff forever changed the landscape of Baylor football, 40 years later, his student, Turner, is focused on changing the landscape of the nation's public education system and moving it into the 21st century.

"I am always looking for ways to make a greater impact on kids," says Turner, who is Superintendent of Coppell [Texas] Independent School District and also serves as president of the Texas Association of School Administrators. "When I became an educator, I did not set out to be a superintendent. I wanted to help children achieve their dreams. In every step I've taken in my career, I believed I could make decisions to help them reach their potential."

Named Texas Superintendent of the Year for 2012 by the American Association of School Administrators, Turner was drawn naturally to teaching, calling education the family business since both of his parents were educators. He spent six years in the classroom teaching science and coaching before stepping into the role of principal in Van [Texas] Independent School District, then serving as superintendent in four school districts across the state: Van, Jacksonville, Burleson and Coppell, where he is today.

Cindy Warner served on the Coppell Independent School District school board for 12 years and was a board member when Turner was hired at the district.

"We wanted someone who was willing to make changes," Warner says. "In fact, during the interview process, I spoke with a school board member from one of his previous districts and he said, 'Turner moves too fast.' He was a good fit for the Coppell district."

The 59-year-old moves quickly for a good reason -- the students, pushing for action, saying, "These kids can't wait, so we can't slow down. We have to keep moving forward."

Baylor's School of Education was the catalyst for his future path. When he enrolled in 1992 to receive his practicing doctorate in education, he had served as a superintendent for two years, and says, "I was seeing a disconnect of what we were doing at school and what society was expecting of the school." Baylor helped him discover what he believes to be the underlying problem when it comes to public education. While society has evolved over the years, the public school system has not, producing products -- high school graduates -- for which society no longer has a need.

"It gave me the sense that we need to change the system. I assumed the role of the change agent, and that was a big change in my career." In Coppell, Turner has begun to create the school of the future by providing a wide array of opportunities for all students to succeed, engaging students in learning and integrating technology into lessons.

On the state level, Turner is involved in legislation, believing it is important for educators to have a greater voice in the debate over public school policies such as high stakes testing. In the 2011-12 legislative session, Senate Bill 1557 passed, approving the creation of a pilot program known as the Texas High Performance Schools Consortium. This program involves 20 schools throughout the state and may be the model for future public schools, focused on developing innovative learning strategies and improved assessment and accountability standards.

As a leader and visionary when it comes to public education, Turner is determined to make a difference in the lives of students; one step at a time.

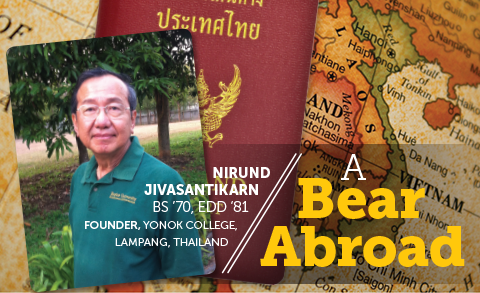

Attending college and earning a degree is the dream of millions of Americans, but this dream almost did not exist for Nirund Jivasantikarn, a native of Thailand -- until the one day it became his reality.

Jivasantikarn was considered one of the lucky ones in Thailand, being accepted into a government-owned and managed medical school after graduating from high school and passing a rigorous exam. After attending the school for a short time, however, he felt disillusioned and returned home. His life's path was forever altered shortly thereafter when his family met an American Peace Corps volunteer from Texas who helped his brother attend Tyler Junior College-Lindale. Jivasantikarn soon followed.

At TJC, he discovered an atmosphere like none he had known before. He became involved in the Baptist Student Union (BSU), made friends, attended classes and participated in every aspect of college life, realizing then what he had been missing in Thailand.

"I became engaged," Jivasantikarn recalls. "I enjoyed the lectures and class discussion, and I had a part-time job, making money for the first time in my life. I watched television and learned the American culture and food, and I became a Christian."

Baylor was the next stop for Jivasantikarn, earning his bachelor's degree in science in 1970 before returning to Thailand to help his brother open a school. After teaching and serving as the director of the school for seven years, he decided to return to Baylor and earn his practicing doctorate degree in education.

Ultimately, with a strong desire to re-create his American university and college experience in his homeland, Jivasantikarn established a university in Thailand modeled after Baylor and TJC.

In 1988, the doors of Yonok College were opened in Lampang, Thailand, to 125 freshman students. Staying true to his vision of offering a personal experience for every student, Jivasantikarn designed and taught a special course called "How to be Successful in College." Meeting once a week, he taught students the valuable lessons he wished someone had taught him at an early age, such as how to use the library, manage time and take notes. He also founded a BSU group on campus and the Lampang Baptist Church.

He maintained his ties with Baylor, offering a teacher exchange program called "Baylor-in-Thailand." One of the first exchange teachers was Dr. Kirk R. Person, BA '88, who says his first impression of Jivasantikarn was of "a man in motion -- full of ideas, curious about many things, eager to get good things started."

At age 68, Jivasantikarn is retired from the university but is not ready to slow down, making Teach Thailand Corps, an additional teacher exchange program, his new mission. This time, he is asking American college graduates to commit a year to teaching English in Thailand's underserved primary and secondary schools.

"Looking back, I believe I've impacted more lives as a teacher than I would have as a medical doctor," says Jivasantikarn. He and his wife, Petcharin -- who is a medical doctor -- have two children; daughter Nock is a Baylor graduate, and son Nick has degrees from Stanford and Johns Hopkins -- additional proof that dreams do come true.

Joel McIntosh dreamed of being a teacher -- until he realized he could make an even bigger impact on children by educating their teachers and parents.

"I have a tremendous respect for educators," says McIntosh, whose mother, Janis McIntosh, BA '70, MSED '72, EDD '79, earned three degrees from Baylor. "For me, education is purposeful. You can't find a more noble profession."

Twenty-four years ago, McIntosh was a high school English teacher when he founded Prufrock Press, named for a T.S. Eliot poem and today one of the nation's leading independent publishers of educational books and materials for gifted, advanced and special needs learners.

After being selected to develop curriculum at his school for a gifted and talented program, he attended his first gifted and talented conference in Austin. The idea for the publishing company was the result of that conference. He wanted to publish the best practices of fellow attendees in a journal format and send it across the state to other educators in need of curriculum support.

The Prufrock Journal, the first product of Prufrock Press, provided teachers with strategies and curriculum to be used in the classroom, just as McIntosh, who left the classroom to devote himself full-time to publishing, had hoped. Today, with offices in Austin and Waco, Prufrock provides research-based materials for teachers and parents of gifted, advanced and special needs learners across the nation -- a success resulting directly from its publisher's desire to make a difference in gifted education.

"While I think teachers do amazing things, I thought I could continue to touch and improve the lives of more kids by teaching teachers than by staying in the classroom," says McIntosh, who completed his master's degree in gifted education from Baylor in 1991. "In 2012, we sold 300,000 books. For me, the greater purpose was that I could do more influencing the lives of kids as a publisher than as a teacher."

The impact he continues to make on education is not lost on Dr. Todd Kettler, BA '91, MSED '94, PhD '12, an assistant professor at the University of North Texas, who met McIntosh in the master's program at Baylor.

"He is innovative. He is an entrepreneur, and he is gifted intellectually," Kettler says. "He can speak across all levels of gifted education, from scholarship and education to parental needs. He is a great conduit and a critical bridge connecting researchers, teachers and parents."

McIntosh, 50, was presented with the President's Award in 2008 by the National Association for Gifted Children for his distinguished contribution to the field.

A life-long learner who had to contend with his own reading difficulty at a young age, McIntosh credits his success to several inspirational mentors who took the time to guide him on his educational journey. In many ways, his publishing company is doing the same for thousands of others.

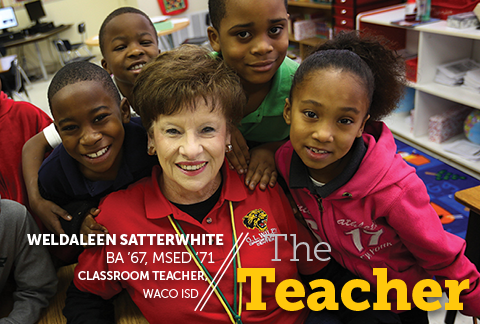

Eccentric, sincere, tough and smart - just a few words used to describe a beloved elementary school teacher who has spent the last 40 years bringing out the best in every student who has had the privilege of sitting in her classroom. Weldaleen Satterwhite's recipe for success as an educator is a simple one: Earn their trust.

"There was never, ever, ever a time in my life that I didn't want to be a school teacher," Satterwhite, 68, says. "I'm from a family of school teachers. I can't explain it, maybe it's a calling, but I do it because I love it. At this point in my life, I don't have to teach. I'm here because I want to be here."

In fact, Satterwhite retired from teaching in 2005 but was immediately rehired, continuing her career at the same school where she began, Viking Hills Elementary in the Waco Independent School District (WISD). Satterwhite has even outlasted Viking Hills, which closed its doors last year. She now teaches in WISD's Elementary Disciplinary Alternative Education program, and enjoys going to work every day.

She has taught children of former students and is the most requested teacher by parents and students alike. This is no surprise to one former parent whose son spent his fifth-grade year in Satterwhite's class. Susan Josephs' son had always had behavioral problems in school, but something changed in Satterwhite's room. She named him student of the month; she made him her friend; and she helped him excel in his studies.

"He would do anything for her," says Josephs, BA '73, MS '77, "and she brought out the best in him." This young student recently turned 30 and is getting married soon. He asked his mom to invite his favorite teacher to the wedding: Mrs. Satterwhite.

Countless stories like this one have kept this life-long teacher in the classroom. One of her favorites was a telephone call from a former student who wanted to let her know that he was about to graduate from college.

"In a way, it's selfish," Satterwhite says. "I get such a good feeling when I'm helping someone, and it's all worth it."

Known for her red-framed school memorabilia that lined the walls of her classroom at Viking Hills and stretched into the hallway, Satterwhite is small in stature and full of energy. She easily stays one step ahead of her students at all times, redirecting their attention when necessary and always showing them how much she cares.

While a variety of teaching strategies, curriculum changes and accountability processes have come and gone in the past four decades, Satterwhite worries today about the toll that high stakes testing is having not only on fellow teachers but on students as well. Her advice to future teachers? "Make sure you are called to this profession. It is hard work and requires more time than just a regular school day."

That's experience talking, and generally speaking, when Mrs. Satterwhite talks, people tend to listen.

From the first day he walked into school as a kindergartner, Robert Duron was hooked. In fact, after 32 years in teaching, coaching and serving as a principal and superintendent in Texas schools, he still remembers that first day fondly.

"I loved being in school as a kid," says Duron, who joined the Texas Education Agency (TEA) as deputy commissioner for finance and administration a year ago. At the agency, he oversees grants, school funding, financial audits, information systems, accounting, budget and planning, federal program compliance and statewide data systems.

"The opportunity to work with the TEA excited me," Duron explains of his move. "I get to remain involved in education, which has always been my passion, and I bring my educational experience to the job."

Most recently this experience includes serving as superintendent of schools for the San Antonio Independent School District, where he made incredible financial progress for the district. In his six years leading SAISD, Duron cut the district's operating budget by $64 million, increased its fund balance by more than 20 percent, and helped pass a $515 million bond package.

As Duron, 55, gained tenure at the highest level of school administration, one of his greatest champions and mentors watched with pride. Dr. John Wilson, MM '71, a clinical professor in Baylor's School of Education, took Duron and several other graduates from Baylor's Scholars of Practice program under his wing and groomed them to become leaders in school administration.

Wilson, who was a visiting professor for the program and a superintendent when he met Duron, remembers telling him and the other graduates to take chances, and Duron took the challenge. In fact, the Scholars of Practice program, which earned graduates a practitioner's doctorate degree in education, was the catapult for his career, and while he has continued to move into more administrative roles, he has never lost sight of the reason he become an educator in the first place: a love for learning.

"Robert has a strong passion for public education and the students he serves," Wilson says. "He carries himself well, he understands the issues, and most importantly, he has a heart for the children."

This passion for education remains the driving force behind Duron's career choices, and he hopes the same passion is what young educators feel when they join the profession too.

"If you are at ease and comfortable in a loud cafeteria or a school bus full of kids, than you are meant to be in education," says Duron, whose father was a teacher and coach and whose wife, Jodi, is also a Baylor graduate (BS '91, MSED '93, EDD '00) and educator.

Maintaining a connection with students seems to inspire Duron, who admits to seeking refuge from stress in his favorite place -- on a school campus. While serving as an administrator, he would often take a walk through the cafeteria or visit a classroom, knowing that the enthusiasm he had on his first day of kindergarten would be rekindled in an instant.

Once upon a time, a degree in education only meant one path for graduates -- teaching. Today's global landscape, however, is creating a greater need for collaboration among disciplines and a degree in education opens a much wider path of possibilities. For Dr. Majka Bree Woods, the path led to medical school.

As an educational researcher for the University of Minnesota Medical School, Woods blends the medical knowledge from leading medical professionals with her educational background to ensure the best curriculum for students. Medical education can be fragmented, with physicians and researchers teaching on a part-time basis in their particular area of expertise. Woods updates them on the university's teaching methodologies and thought processes in order to align teachers and courses with the school's mission and goals.

"My day is split among various administrative duties," says Woods, who has two titles at the university: assistant dean of assessment, curriculum and evaluation, and director of medical education development and scholarship.

"In the undergraduate medical education program, what everyone else in academia calls graduate school, I work directly with faculty to ensure we are delivering the best possible medical education experience for our students so they can deliver the best possible patient care when they graduate." The medical school enrolls more than 2,200 students across two campuses in the Twin Cities and Duluth, with 3,800-plus faculty physicians and scientists.

"I get to see a lot of variety in my job," Woods says. "I work with faculty, staff and students, and because I bring the education piece to the table, I have the opportunity to talk about the practices I love. I'm able to think about the situation or task and bring my expertise -- critical-thinking and assessment evaluation -- and be involved in real-time research."

A few of the other pieces in Woods' job description include networking with other medical schools, sharing best practices, and faculty development.

"One of her many strengths," says Leslie Anderson, the school's chief of staff, "is her ability to ask the right questions in a non-threatening way, and her opinion is valued highly. In fact, her opinion is highly sought after. I think she has contributed quite a bit to helping us focus on our mission and define our objectives in order to keep them as the focus of what we do."

Woods, 41, refers to Baylor, which she attended as an undergraduate and graduate student, as the foundation for her success. And while teaching has been part of her life since an early age, volunteering to teach summer school around age 14, she never dreamed she'd be where she is today.

"The Baylor doctoral program gave me many opportunities and exposed me to many various areas and different people, while my undergraduate years pushed me towards service and community," Woods explains. "I've chosen all my jobs based on how I can help other people. That was my mainstay at Baylor. It is important to know how to maintain your integrity as you move the field and individuals forward. I've come to realize that I can help effect change one person, one job or one project at a time."

Are you a Baylor School of Education alum who has received local, state or national recognition for achievements in your field? Do you know someone else who has been recognized? Tell us your story! The School of Ed wants to honor its outstanding graduates in the coming year. Please share information about your honor at www.baylor.edu/SOE/recognitions or by email at BaylorImpact@baylor.edu.