Farewell to Floyd Casey

When Baylor plays its final football game in Floyd Casey Stadium against Texas this December, a 63-year story containing some of the most exciting football moments in the state will come to a close.

As the most recent Baylor football coach to experience the thrill of leading a team to victory in Floyd Casey Stadium, Art Briles says he's looking forward to the "one great season" left in the stadium this fall.

"We'll always remember the growth and excitement of Baylor football over the last five years, not just what we've experienced on the field, but from the standpoint of the support of Baylor Nation and the success we've had in Floyd Casey Stadium," Briles says. "We're 16-3 over the last three years, which is as good a home record as anybody in the Big 12. The Case has hosted a bunch of great memories."

The story of how Baylor built Floyd Casey and is now constructing its newest stadium is one with many twists and turns. The university began playing intercollegiate football in 1899, and during the first 50 years it made do with a succession of fields and stadiums that varied widely in quality. Most of Baylor's first home games were played on what was called the West End field, little more than a flat, open space near the end of a westerly Waco streetcar line.

Thanks to a generous donation from Lee Carroll, whose father and grandfather had provided funds for the Carroll Science Building and Carroll Library, respectively, Baylor was able to begin using its first on-campus gridiron, Carroll Field, in 1902. For the next 33 years, Baylor played its home games on Carroll Field -- with the exception of four years in the 1920s when it used Waco's Cotton Palace field instead.

In 1936, Baylor began playing its home games on another off-campus gridiron, the city-owned Waco Municipal Stadium. The 20,000-seat stadium at 15th Street and Dutton Avenue often hosted exciting Southwest Conference battles before packed houses, but over time its shortcomings presented problems for Baylor.

Dave Campbell, BA '50, the veteran Waco sports editor who saw his first Baylor football game in Muni Stadium as a 12-year-old boy in 1937, says the stadium, which Baylor shared with Waco High School, was in decline after World War II.

"It was the best field in (Waco) at the time, but they weren't keeping it up," Campbell says. "And there was no parking to speak of -- you had to park on the streets. Baylor obviously needed a new stadium."

Under coach Bob Woodruff, whom Campbell says was a great recruiter, Baylor was fielding excellent football teams in the late 1940s. But those winning teams weren't translating into financial boons for the university.

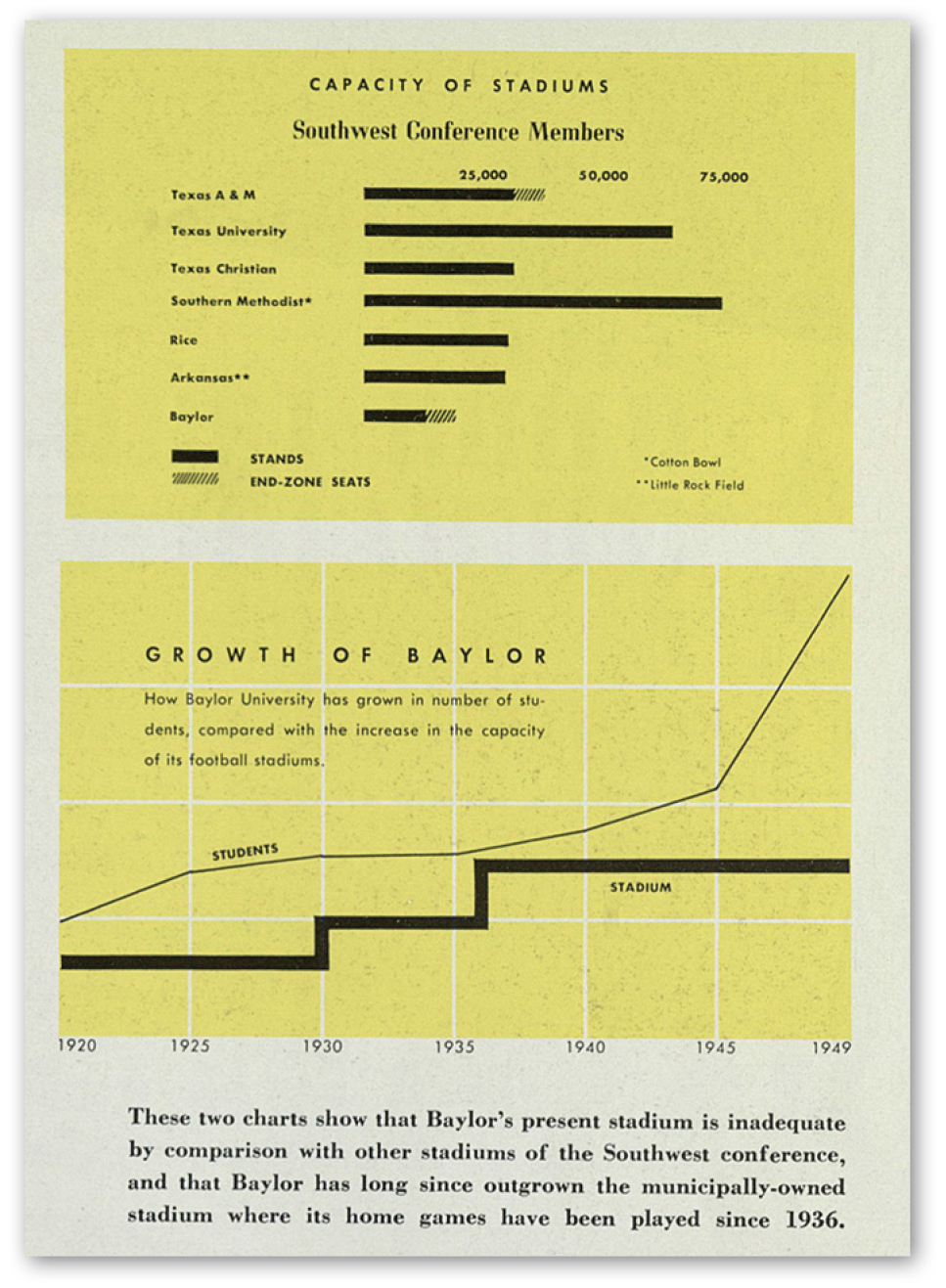

While Muni Stadium could hold 20,000 fans, every other Southwest Conference stadium was larger -- some considerably so -- and could sell more tickets, providing bigger payouts for both teams. For that reason, Baylor's conference opponents were becoming less and less willing to travel to Waco.

By the start of the 1948 season, coach Woodruff was telling Waco businessmen that if Baylor wanted to remain in the Southwest Conference it needed a new and bigger stadium.

On Dec. 9, 1948, the Waco City Council voted to offer Baylor the grounds of the defunct Cotton Palace on which to build the stadium, but the university ended up rejecting that offer because of a lack of space for parking and the added expense required to correct a geological fault on the property.

Instead, on Feb. 15, 1949, Baylor purchased 100 acres of land away from campus on high ground along old Highway 6 (now Valley Mills Drive) for $101,318. Campbell says there had been no serious discussions of buying land closer to campus because Baylor was surrounded by homes and businesses, and because in those days areas near the Brazos River were prone to regular flooding.

"It's all very nice now (along the river), but at that stage it wasn't," Campbell says.

In March 1949 university officials and alumni joined with local business leaders to form the 500-member-strong Baylor Stadium Corp. The group would issue 30-year stadium bonds at 3 percent interest to fund the estimated $1.5 million cost of the stadium.

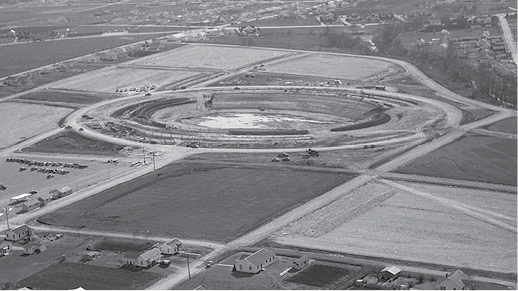

Baylor President W.R. White (top left) tips his hat on the podium during the groundbreaking ceremony of the Baylor Stadium on May 28, 1949. The Baylor Stadium Corp. published a pamphlet called "The Invisible Line" (below), in 1949 providing statistics to make the case that Baylor University needed a new football stadium. At the time, Municipal Stadium was being shared by the Bears and Waco High School. An aerial view of the early stages of construction shows an almost rural location.

On May 28, 1949, Baylor observed a pair of groundbreaking ceremonies. That morning on campus, ground was broken for the long-awaited Tidwell Bible Building. Later that day, a crowd of 4,700 people showed up at the future Baylor Stadium site to watch the groundbreaking ceremony and feast on 3,300 pounds of barbeque.

Waco residents were asked to donate to the stadium's cost, and on Aug. 4 a mile-long parade was held in downtown Waco to kick off the local fundraising campaign. Flamboyant multimillionaire oilman Glenn McCarthy, who had just opened the luxurious Shamrock Hotel in Houston, and Texas attorney general and Baylor alumnus Price Daniel rode horseback and served as parade marshals.

"Baylor friends in Houston will do their share in building the new Baylor stadium (and) I intend to buy a substantial number of stadium bonds myself," McCarthy said.

Baylor coed Jane Heath of San Benito was later named "Miss Baylor Stadium" from the 11 nominees who took part in the parade.

On Nov. 5, the contract for building Baylor Stadium was given to Swigert Construction Co. of Waco, which had turned in the low bid of $1,127,188. At the time, Swigert was also busy building the Armstrong Browning Library.

Stadium bonds sold steadily, attracting even non-Baylor buyers such as University of Texas athletic director Dana Bible. On Dec. 2, 1949, in Austin, Gov. Allan Shivers proclaimed the day as "Baylor Day" in Texas and took the opportunity to purchase some stadium bonds himself after Baylor President W.R. White announced that the campaign was only $500,000 shy of its goal.

Woodruff resigned as head coach on Jan. 6, 1950, to accept a head coaching job at Florida. Baylor hired Navy coach George Sauer two weeks later to succeed Woodruff, and the march toward the stadium debut continued.

First Game

Even though only 30,000 of the eventual 50,000 seats were installed and finishing touches were still being applied, fans, including Gov. and Mrs. Shivers, jammed the roads leading into Baylor Stadium on Sept. 30, 1950, to help dedicate the structure and enjoy the first game.

Baylor easily won the contest, a non-conference matchup with the University of Houston, by a score of 34-7. The 25,000 people who attended were the most people to watch a football game in Waco up to that time.

By the time the first Homecoming game in Baylor Stadium took place on Oct. 28, 1950, the number of completed seats had increased to 41,000. That first Homecoming matchup was also the first Southwest Conference game played in the stadium, and Baylor fans rejoiced as the Bears beat Texas A&M 27-20.

It wasn't long after Baylor Stadium opened that it began being used for things other than football. On May 27, 1951, 862 students received their degrees in the first Baylor commencement held at the stadium. Bad weather played havoc with other ceremonies held there, so commencement moved indoors to Waco's Heart O' Texas Coliseum beginning in May 1956.

Another early non-football use of the stadium was for ice skating. On June 2, 1952, the Ice Vogues show opened as a fundraiser for Baylor athletics. Four large tanks of water were installed on the field and then frozen to provide an icy surface for the show.

After a tornado struck Waco on May 11, 1953, killing 114 people and demolishing much of downtown, hundreds of military and civilian rescue workers came to town to help. Servicemen from nearby Fort Hood were housed at Baylor Stadium while assisting with cleanup operations, and some of the tornado debris was buried in low-lying areas on the stadium property.

Let there be light

The new Baylor Stadium was constructed without lighting for night games. On Feb. 16, 1955, Baylor trustees approved adding four sets of lights on each side of the field, which were installed in the summer of 1955 at a cost of $68,000.

The first night game played in Baylor Stadium was a Sept. 17, 1955, non-conference contest against Hardin-Simmons University. The normal expected attendance would have been about 15,000 fans, but 20,000 defied a citywide bus strike to show up and see Baylor win, 35-7.

The Hardin-Simmons win was not enough to keep 1955 from being the first losing home season in Baylor Stadium. The Bears won two games at home that fall while losing three.

The value of Baylor Stadium in accommodating large crowds and increasing game revenue was truly proven during the 1956 Homecoming game against coach Bear Bryant's Texas A&M squad, with both teams nationally ranked. The crowd of Bears and Aggies that showed up on Oct. 27, 1956, is today listed officially at 49,500, making the game the first considered to be an official sellout of Baylor Stadium.

"In my mind, (it's) the largest crowd I've ever seen in Baylor Stadium. The crowd was so large they filled both end zones, and they had policemen down in the end zone keeping the crowd back," Campbell says. "They really had all the people they could handle."

Despite the great show of support, the Bears lost, 19-13.

Making history

The completion of the first substantial expansion marked the close of the stadium's first decade. In spring 1959, in a $100,000 project sponsored by the Baylor Bear Club, Baylor moved its athletic offices from Rena Marrs McLean Gymnasium to new structures under the stands of the stadium that also housed larger training facilities and dressing rooms as well as a new projection room.

The first nationally televised football game in Baylor Stadium had been the 1954 Texas game -- which Baylor won -- but in 1966 another televised home game made Southwest Conference history.

In a game against Syracuse in Baylor Stadium on Sept. 10, 1966, Baylor halfback John Westbrook became the first African American athlete to compete in a Southwest Conference sporting event. With a national television audience of 60 million people watching, Westbrook entered the game in the fourth quarter and carried the ball for 11 yards in Baylor's 35-12 upset victory.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were some of the most challenging football years for the Bears. Between 1967 and 1971, Baylor posted a 7-43-1 record and in 1969 recorded its only winless season in the modern era.

Changes on the horizon

Baylor's football fortunes -- and those of Baylor Stadium -- began looking up in 1972 with the arrival of new head coach Grant Teaff. Taking a job he says felt called to, despite the fact that no one else at the time seemed to want it, Teaff left Angelo State for Baylor and was disappointed with the state of the stadium he inherited.

"I took the job without seeing the facilities (and) I was heartsick, because my facilities at Angelo State were 100 times better," Teaff says. "There were no practice fields (at Baylor), so every practice was on the stadium field and by the end of the season there wasn't a blade of grass left."

Teaff added that the stadium's original wooden seating was in bad repair, the dressing rooms were "a disgrace" and the tiny weight room contained a single universal gym machine. He immediately began working with trustees and donors to raise the funds needed for improvements to the stadium and the playing field.

"I said look, we need to raise the money to get AstroTurf on this field. We can't compete unless we have it. I can't recruit players because Texas and other Southwest Conference schools had AstroTurf," Teaff recalled.

Changes came quickly. Before the start of the 1972 season, Baylor Stadium Corporation directors and Baylor trustees approved spending $400,000 to put the first artificial turf in Baylor Stadium, and donors helped pay for a new weight room and other upgrades. Around the same time, members of the Baylor "B" Association spent $150,000 to build the Baylor Lettermen's Lounge under the northwest stands.

During Teaff's inaugural 1972 season with the new artificial turf of Baylor Stadium, the Bears improved to 5-6. Two years later, in a turnaround dubbed the "Miracle On the Brazos," Baylor went 8-4 and won the Southwest Conference championship for the first time in 50 years.

The Texas game in Baylor Stadium in 1974 is considered the most memorable from that championship season. Baylor had not beaten Texas since 1956, so when the Bears came from behind at halftime and handed the Longhorns a 34-24 loss it erased almost two decades of frustration.

"People went crazy," Campbell said. "Some had left the game early, figuring it was all over. One (person) got as far as McGregor while listening to the radio and came back to watch the end of the game."

The victory was so momentous that Baylor Herbert H. Reynolds, then executive vice president, and other university supporters left the scoreboard lights on and spent the night at the stadium.

"I thought, well, that's pretty indicative of how important that game was," Teaff says. "(That win) never goes away because it was so dramatic."

Six years later in 1980, Baylor won another conference championship -- and the Baylor Stadium Corp. finally paid off its 30-year construction bonds.

Staying competitive

Important enhancements were made to the stadium during the 1980s. In 1986, stadium complex landscaping improvements worth $100,000 sponsored by the Greater Waco Beautification Association were dedicated. The following year, one of the most significant improvement campaigns in the stadium's history was launched.

At a news conference on July 24, 1987, Baylor athletic director Bill Menefee announced the start of a fundraising campaign to build a new North End Zone Complex that would house all athletic offices, a ticket office, Bear Club offices, a larger weight room and a VIP room. Baylor Hall of Famer Gale Galloway and his wife Connie provided the lead gift to ensure the project's completion.

Teaff says the improvements were needed to keep Baylor competitive.

"We've done well with what we've got and we've never apologized for our facilities," he told reporters. "But there comes a time where needs come to the top."

In fall 1988, Baylor trustee Carl Casey of Dallas, a 1931 graduate, joined with his wife in giving $5 million to the $8 million stadium improvement campaign. In gratitude, Baylor renamed the 38-year-old facility Floyd Casey Stadium -- in honor of Casey's father -- at a ceremony during halftime of the Homecoming game against Arkansas on Nov. 5, 1988.

Renovation of Floyd Casey Stadium began in January 1990. The first phase of the project, completed in time for the 1990 football season, featured expanded and improved restroom facilities as well as new stadium lights, concession stands, a new press box elevator and an All-Pro Turf artificial playing surface.

The second phase of stadium renovation, which included construction of the North End Zone Complex, was completed in time for the 1991 home opener against the University of Texas-El Paso on Sept. 7.

Significant stadium enhancements funded by numerous philanthropic gifts continued throughout the life of Floyd Casey Stadium. These included:

- Installation of the stadium's first video scoreboard, funded by a donation from the J-Hawk Corp. -- Jim and Nell Hawkins (1995);

- Creation of the Snickers Touchdown Alley dining and entertainment area adjacent to the stadium (1995);

- A return to a natural turf playing field and improvements to the team's practice fields were championed by Dary Stone, Joe Armes and Tom Powers (1998); and

- An expansion of the press box and an increase in luxury suites, more than tripling the square footage of the area and creating a new facade for the west side of the stadium (1999). This area was later named in honor of Jay and Jenny Allison who generously supported numerous stadium improvements.

The larger press box included the new Dave Campbell Media Center, donated by Campbell's good friend Bernard Rapoport of Waco.

"I was honored and flattered by that, and I still am," Campbell says.

The expansion of the press box was just part of the improvements included in the Grant Teaff Athletic Complex, begun in 1998 and encompassing football stadium projects such as the Mathew Dove Letterwinners Plaza, paved parking, landscaping and a new entrance off of Clay Street.

Baylor Stadium football highlights during the 1990s include Coach Grant Teaff's final home game, a 21-20 victory over Texas on Nov. 21, 1992, and the Baylor-Texas game on Nov. 1, 1997, where joyous fans celebrating the Bears' 23-21 victory pulled down one set of goalposts and carried it back to the main campus.

Baylor's next-to-last football game in 1996 was the university's final Southwest Conference contest in Floyd Casey Stadium -- a 34-6 win over Rice on Nov. 18. Baylor began Big 12 Conference play the next year, with the first Big 12 game played in Floyd Casey being a close loss to Oklahoma on Oct. 19, 1997.

During the 21st century, Floyd Casey Stadium has continued to play host to many exciting and inspiring moments.

On Oct. 30, 2004, Baylor broke its 19-year losing streak against Texas A&M with a 35-34 upset of the nationally ranked Aggies in the Case. Once again, delirious Baylor fans tore down a set of goalposts and walked it back to campus.

Two years later, on Oct. 28, 2006, another heated battle with Texas A&M brought 51,385 people to Floyd Casey -- the largest crowd in stadium history.

One inspiring stadium event during this period had nothing to do with football. On New Year's Day 2005, 30,000 friends, family and supporters gathered at Floyd Casey Stadium for an emotional sendoff for 3,000 Texas National Guard troops headed to Iraq -- the largest Texas Guard deployment since World War II. U.S. Sen. John Cornyn and Texas Gov. Rick Perry were there to help say goodbye.

New attitude

The arrival of Baylor head coach Art Briles has brought Floyd Casey Stadium some of the most spirited and successful gridiron matchups in its long history.

From his Baylor debut at home on Aug. 28, 2008, coach Briles has compiled the second-highest home winning percentage in stadium history (69 percent), which could pass coach George Sauer's home winning percentage of 70 percent with a good season by the Bears in 2013.

Led by Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback Robert Griffin III, the Bears during the previous five seasons have achieved the first-ever Baylor football victory against Oklahoma -- a 48-38 win at home on Nov. 19, 2011 -- as well as only the third unbeaten home season in Floyd Casey Stadium history in 2011.

Decision time

When it came time to once again consider upgrading Floyd Casey Stadium to keep it current with other conference football venues, an additional option was put on the table -- building a new stadium on campus.

"Several years ago we did a study to look at what it would cost to renovate Floyd Casey Stadium and bring it to upper echelon Big 12 standards, it was going to cost between $80 million and $100 million to renovate," Baylor athletic director Ian McCaw says. "We looked at what it would cost to build a new Baylor Stadium, and that came to about $250 million. As we looked at it and evaluated the opportunity to come back to campus, as well as the fundraising potential for each option, we felt it would be much better to build a new stadium. Following a transformational gift from Drayton McLane and the McLane Family, other Stadium Founders created momentum for the project. The financial support from Baylor Nation has been overwhelming."

When Baylor meets Texas this Dec. 7 for the final game of the 2013 regular season, it will also be the 342 -- and last -- football game ever played in Floyd Casey. And though the next chapter of Baylor's football story will be written on the field of a new stadium on the Brazos River beginning in 2014, memories from 64 seasons at Floyd Casey will be preserved.

"We're definitely going to have a donor recognition area in the new stadium to honor contributors to Floyd Casey Stadium, and that will allow us to celebrate its history and also recognize all those generous donors," McCaw says. "That's very important to us, so we are going through and looking at items we can bring over to Baylor Stadium."

There will also be a number of special events held at Floyd Casey during the final season to commemorate the stadium.

"It's going to be a year of great celebration of our history and an opportunity to bring back a lot of former players, coaches and staff members who have been a part of Baylor football over the years," McCaw says. "We're excited about that."

While many names of beloved players, coaches and friends have been listed in this article, there are many more who invested time, talent and treasures throughout the more than 60 years of Floyd Casey Stadium. The spirit of generosity continues as we look toward our new on-campus stadium.