Where There's Will, There's A Way

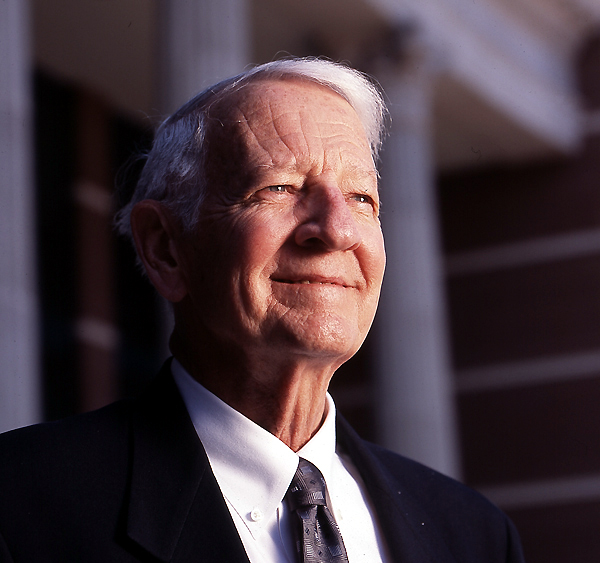

When Will Davis was elected chair of Baylor's Board of Regents May 14, 2004 -- by a narrow margin of 18-17 -- he knew he had a tough job ahead of him. Also at that meeting, the 36 members of the board reportedly voted by the same count, 18-17, to support the leadership of President Robert B. Sloan Jr. (one member was absent). The regents had been at loggerheads most of the past year over Sloan's leadership, primarily because of the divisions that had mounted under his watch within faculty and alumni groups. The May vote marked a precipitous slide since Sept. 12, 2003, when regents voted 31-4 to endorse Sloan. Into the divide came Davis, BBA and LLB '54, a soft-spoken, amiable man with snow-white hair who seems better suited for the role of grandfather than of diplomat. He is, however, both -- and one year later, the man who has four grandchildren at Baylor has moved two separate, unyielding camps toward middle ground. "I was not anxious to do this," he says of the chairmanship. "But when 18 regents ask you to assume a leadership role on the board, it's virtually impossible -- if you care anything about the institution and the board -- to say no." And, it would seem, it is impossible to say no to Davis himself. In the past year, he has met often with regents, faculty groups, alumni, donors and Sloan to assess the situation and to promote discussion and reconciliation. "I knew it would take time and patience," he says. "I knew it would be very tough, very hard, but I really believed I had skills as good as anybody else and maybe better than some. And I knew my commitment was to Baylor, and that was the only commitment I had." His first priority was to unify the board. "It is no secret that the division among the 36 regents occurred around Dr. Sloan's leadership," he says. "That was the issue." Although the regents generally respect and admire Sloan and what he accomplished in his decade as president, he says, "there were regents who felt he had lost his ability to lead the entire constituency, particularly faculty and alumni. When that happens, you've got a couple of choices: You've got to try to go forward with a fractured leadership or to make a change in leadership. Once you've lost it, there's no sense trying to get it back." From June to mid-November, Davis says, he met often with Sloan, who had asserted throughout the past two years he did not intend to resign. With the next regents' meeting not scheduled for several months, Davis says "there was a good period of time in there in which patience and respect for one another allowed these issues to germinate, and for Dr. Sloan to come to his own conclusion about whether he thought it was time for him to give up the presidency and to do something else." On Jan. 21, Sloan and Davis jointly announced that the president would transition to the role of chancellor beginning June 1. In his remarks, Sloan spoke respectfully of Davis, thanking him for his "statesmanlike leadership ... calm demeanor and dedication to fairness." He also thanked Davis for "his wise counsel and his friendship," stating that he trusts him and has "great confidence" in his leadership. "Whatever part I had to play in it was as a counselor, not as a person shoving him out the door," Davis says. "I didn't do that. He made the decision himself, without pressure from me or anybody else. But I do think it was the right decision at the right time." Re-elected chair unanimously by the board in April, Davis continues to work at reconciling the Baylor family, coming to Waco about every other week to meet with different groups. A partner in the Austin law firm Heath, Davis & McCalla, PC, he maintains his practice while serving on the Regent Search Committee as it considers candidates to be Baylor's 13th president. He has met with Baylor's Faculty Senate, with the campus chapter of the American Association of University Professors and also with leaders of the Baylor Alumni Association. "I can't think of any reason why there should be continuing animosity among faculty, regents, alumni or any other constituency group, because, as I understand the criticism to this point, it's all been directed pretty much at Dr. Sloan's leadership or lack thereof," Davis says. Leadership is a quality Davis knows. In fact, he may be the only person who has been president of the Baylor Student Government (helping to organize the group in 1953 and serving as its first president), president of the Baylor Alumni Association (1967) and chair of the Board of Regents, where he served from 1972 to 1982 under President Abner McCall, and from 1999 to the present. "I think it's unusual," he says, "and I'm very pleased that at least on those three occasions, I was selected to be leader." Davis also has been a strong voice for elementary, secondary and higher education in the state. He has served as president of the board of Austin ISD; was a founding member of Austin Community College, serving as its first board chair and as a member for 10 years; a member of the board of St. Edward's University in Austin; a member of the Texas State Board of Education and at one time its vice chair; president of both the Texas Association of School Boards and the National School Board Association; and a member of the state Coordinating Board for Higher Education. There is an elementary school in Austin that bears his name, an honor he describes as "one of the biggest shocks and surprises" of his life. Given his mother's influence on his life, his commitment to education is not surprising. He is the only child of a single mother -- the first in her family to receive a college degree -- who gave up school teaching so she could earn an extra $10 a month working for the state to better provide for her child. She divorced Davis' father, whom he describes as a "worthless, alcoholic drunk," when the boy was about 4 years old. "She knew that her heart was in teaching, but she needed to raise a child," Davis says. "To me, she was a saint, that's the long and short of it." It is a similar devotion to family that steered Davis away from what many assumed would be a promising career in state politics. He was at one time chair of the state Democratic Party, but he chose not to pursue public office. "I felt a stronger commitment, frankly, to my family, to the kids. The fact that I had been a child of a single mom showed me some real deficiencies in how things are supposed to be in a family," he says. "I wasn't about to go off and abandon my children and become a politician in the true sense of the word." He and wife, Ann, whom he met in Austin and who later followed him to Baylor, have three children and nine grandchildren. Will Davis Jr., BA '84, and Lynn Walker, BSHE '82, graduated from Baylor and Lisa Davis graduated from the University of Texas. The Davis family gathers as often as possible at Will and Ann's home in Estes Park, Colo. A late convert to snow skiing, Davis says he's glad he didn't discover it sooner or he might have been in serious danger of becoming a "snow bum." Always an athlete, Davis was offered two football scholarships out of high school -- one to UT and the other to Baylor. Wanting to get out of his hometown, he came north. He was a running back for the Bears, competing in the Orange Bowl against Georgia Tech in January 1952. He had been president of the newly created Student Government for one week when the 1953 tornado hit Waco, killing 114 people and leveling much of downtown. He and several friends were in the Baylor Drugstore, at Fifth and Speight, when it hit. "That was the biggest, darkest cloud, funnel thing, I've ever seen in my life," he remembers. "It was really ugly, mean looking and it was enormous." He says he watched as it came right toward campus. "I was scared to death. Just as it got to Baylor, it kind of raised up and went over the top of Pat Neff and Old Main. Those towers (on Old Main and Burleson) .... just psst! ... gone. Took them right down." Davis organized a group of about 150 Baylor students, and they spent much of the next week helping clean up the debris. "We were down there working, digging all night, pulling people out of the Dennis Building and surrounding buildings, people alive and dead both. That was pretty traumatic." He says he was very proud of the Baylor students. "They rallied, were up all night, two or three days in a row. We had to dig out with our hands. It was a pretty hard deal." While the tornado was a force of nature, someone many have described in similar terms intervened in Davis' life at Baylor in another way. "Judge McCall, for some reason, I don't really know why, intervened with me and called me over to his office," Davis recalls. "He said, 'Davis, you're really not going to make it as a football player. I want you to come over here to law school (in the fall of 1951), and let's see if we can make a lawyer out of you.'" Davis said he'd given no thought whatsoever to becoming a lawyer, or to any plans after graduation. "I was playing football and dating girls and going to school when I thought it was necessary," he laughs. McCall got his attention, though, and Davis graduated cum laude, serving as editor of the Baylor Law Review. "He was a mentor and I was a student of his from then on. We had a good relationship, friends. He was a wonderful man," Davis says. His transformative experience at Baylor laid the groundwork for his passion about education and public service. "The most stimulating period of a person's life, I think, are the college years. There's a tremendous change from the freshman year to their senior year. They mature, and the light goes on. They become very thoughtful, considerate, deliberate adults. "That's what happened to me, fortunately in the hands of a molder like McCall and in a setting like Baylor University," he says. "And I realize that. I recognize that happened to me. I'm indebted to Baylor University, and I have intended to do all I could to pay it back, in any way, shape or form I can."