Do Not Grow Weary In Doing Good

Lindsey Hurt's fingers massage the young girl's neck in small circles starting behind the ears and sliding down toward the child's shoulders. She doesn't get far before her hand stops. "Laila, come here," she calls to her classmate, Laila Nooruddin, also a senior at Baylor's Louise Herrington School of Nursing in Dallas.

"It's some kind of nodule? What do you think?" Hurt asks as Nooruddin gently probes the child's neck, which has lumps along one side. "Oh, my," Nooruddin whispers, as the two exchange concerned looks. Hurt slips away to search for Charles Kemp, a senior lecturer at the Nursing School and creator of the community care clinical course, one of the three main options in the community health clinical.

Hurt returns with Kemp, RN, FNP, FAAN, who has been on the faculty at the Nursing School since 1989. He examines the young girl and diagnoses possible tuberculosis. She is one of five siblings under age 8 taken into the Texas Child Protective Services system for possible neglect or abuse two days earlier and required by law to undergo health screenings within 48 hours. Agape is on call to do these assessments for a privately run emergency shelter.

This August day was earmarked for an intensive eight-hour orientation for the fall practicum scheduled to start the next day, when the eight students would see their first patients. Instead, the first lesson they learn is that some health cases can't wait.

They had begun the day attending a required two-hour orientation at the Dallas Independent School District, followed by a quick lunch at a Thai restaurant and a dash back to the clinic to prepare for the five siblings' arrival. While they wait for the caseworkers, the students practice health assessments on each other. Kemp draws an outline of the human body and demonstrates how to note possible abuse -- an impromptu lesson for the day.

The students also become familiar with the clinic's equipment, which they discover is closer to on-the-edge than cutting-edge. The manual blood pressure cuffs are a far cry from the automated ones they used at the Baylor Medical Center. And forget personal digital assistants (PDAs), the electronic devices most often used today; medical records at the clinic are on paper. Several students cannot get the light to turn on in the otoscope, which is used to examine ears and noses.

Their nervous chatter is punctuated by the sound of plastic bouncing off the linoleum floor as the protective sleeves on the instruments repeatedly slide off. Everyone becomes quiet when the caseworkers bring in the family of subdued, eerily compliant children. Sensing their unease, student Emily Kramer grabs a dog-eared copy of The Tortoise and the Hare from a nearby bookcase. Kramer, who worked last summer at Children's Medical Center in Dallas, sits cross-legged on the floor and beckons the children to her. The youngest, a toddler, climbs into her lap, and the others huddle around her as she begins to read. As she does so, the caseworkers confer with Kemp, and then the children are taken to the five exam rooms, where nursing students wait to begin their work. By the time the children leave nearly two hours later, the students have provided complete assessments, mapped on the body outlines what they observed and diagnosed two long-standing, untreated conditions -- including the little girl with the lumps on her neck. Not bad for a day in which they weren't supposed to see any patients at all.

Ministry to the world

Senior nursing students have three options in the required Community Health Clinical: the Agape Clinic; a rural health clinic in Itasca, Texas, about 60 miles southwest of Dallas; or assisting a public school nurse in the Dallas ISD. Seniors do a clinical for half of the semester, and then complete an internship, usually hospital-based, for the other half. This hands-on, first-person experience exemplifies Baylor's core values of service and excellence, says Judy Wright Lott, DSN, FAAN, dean of the Nursing School and a nationally known neonatal nurse practitioner and researcher.

"I believe that nurses are called to nurse, and particularly at Baylor, we nurture that feeling. We believe that, in the School of Nursing, we are not only participating in Baylor's mission to teach and to do research, but we also see what we do, what we provide for patients, as a ministry," she says. "I really believe that nursing is a very concrete example of the best way to integrate faith and learning and provide that as a ministry to the world."

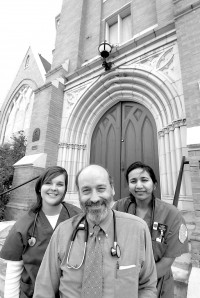

Kemp's seven-week course is a perfect example. The Agape Clinic is in the basement of Grace United Methodist Church just east of downtown Dallas and two blocks from the Baylor University Medical Center, where the School of Nursing is located. Since 2000, the clinic has operated as a joint ministry of Grace United and Baylor Community Care (a ministry and service-learning program of the Nursing School) with broad support from an interfaith network of Dallas congregations. The clinic, known as La Clinica Iglesia by many of those whom it serves, provides medical care primarily to the working poor who have no health insurance and to immigrants.

Though still overwhelmingly Hispanic, the neighborhood around the clinic has hosted wave after wave of immigrants, including the Cambodian refugees that Kemp and Baylor students worked with in 1991 when he created Baylor Community Care and this clinical by going door to door to find people in need of help. Members of the latest wave of immigrants -- a family fleeing genocide in Sudan and still dressed in tribal robes -- are standing on the porch of a prairie-style house next door to the church that is owned by Grace United and shared by the Center for Survivors of Torture and Refugee Services of North Texas. Kemp, chair of the Agape/Community Care board, also has served as chair of the Refugee Services board (see sidebar on Kemp's book, page 25).

To reach the clinic, visitors enter through a side door that is kept locked -- because of the clinic's inner-city location -- except on clinic days, when no one is turned away. Although the church is painstakingly restoring the stained glass on the main level, the clinic itself -- located in the basement across the hall from the church's day care center -- is spare. Metal folding chairs and filing cabinets fill the waiting room. The five exam rooms flank a narrow hallway. In addition to working at the Agape Clinic one day each week, these senior students provide a day of health promotion and community outreach in and around Ignacio Zaragoza Elementary School. The program is supported by a one-year, $10,000 grant from the Aetna Foundation and offered jointly by Agape and the Nursing School. The grant partially funds the salary of a Spanish-speaking promotoras de salud (health promoter) and the cost of educational materials for parents. In addition, Agape Clinic/Community Care had just received a one-year, $20,000 grant through the Dallas Women's Foundation to train part-time health promotoras. In response, the students added to their other duties a three-hour weekly training session for new promotoras. Kemp also sends students out in pairs to knock on apartment doors in the neighborhood looking for people to help. The clinic always is in need of funding, and patients are encouraged to pay for services as they are able.

Expanding programs, classes

There are 108 seniors (46 fall graduates, 62 spring) in this year's class. Baylor nursing graduates have a 100 percent placement rate, and the majority choose to pursue advanced degrees, Lott says.

The seniors in the fall Agape clinical are in class on Mondays and Tuesdays, conduct community outreach on Wednesdays and work at the clinic each Thursday. Friday is devoted to study and jobs: one student works on the renal floor at Children's Medical Center and another works as an emergency medical service technician for two far-flung ambulance companies.

Although many Texas nursing schools have faculty vacancies this year, Baylor is fully staffed. In fact, for its size, the Nursing School has an unusually high percentage of faculty elected by their peers as fellows of the American Academy of Nursing: Kemp, for his work on community and refugee health; Lott and Frances Strodtbeck, the coordinator of the neonatal nurse practitioner program, for their expertise on neonatology.

The nursing students began their journey three years ago, completing the first two years of the bachelor's of science in nursing degree at Baylor's Waco campus or another institution and then entering the Dallas school. Another program allows students with two-year associate degrees to earn bachelor's and master's degrees concurrently. A new program, begun in 2003, is the post-master's certificate for nurse educators -- an option prompted by a national shortage of nursing instructors. In 2003, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing reported national survey data indicating an 8.6 percent faculty vacancy rate, up from 7.4 percent in 2000. Along with limited facilities and clinical sites, the faculty shortage was blamed for the turning away of 15,944 qualified U.S. nursing school applicants in 2003, according to another AACN report.

Other graduate programs offered at the School include family nurse practitioner, neonatal nurse practitioner and an advanced nursing leadership program, which prepares nurses as health care administrators (see "Putting life to the test," page 28). Nurse practitioner is a growing specialty that offers graduates greater autonomy, including prescribing many drugs. Baylor's School first offered the leadership degree in 1990, adding family nurse practitioner in 1998 and neonatal nurse practitioner in 2000. Baylor has graduated 92 students from the three graduate programs.

"The face of health care is changing. It is not just in a hospital now," Lott says. "We need to prepare nurses to be able to deliver nursing care in many different settings."

Already experiencing a shortage, the nursing profession shortfall is expected to worsen. Many of today's nurses will begin retiring just as aging baby boomers will need more care. Registered nurses represent the largest health care occupation in the nation, with 2.3 million jobs, and more new jobs are expected in this field in the coming years than in any other, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (see "In short supply," page 22).

In response, the Nursing School expanded this year's incoming junior class in Dallas by 41 percent, from 68 to 96 students. Lott would like to expand further and add a doctoral program, but that will require more physical space, she says. School administrators also would like to create endowed professorships and a research center. For instance, Lott says, Baylor is an ideal environment to research whether nurses who graduate from faith-based programs are less likely to suffer burnout in a field known for long hours and low staffing.

One way to avoid burnout is to help nurses discover the right niche in their profession. Exposing students to a variety of experiences in clinical rotations helps them choose the specialty or environment that best matches their skills and goals. "Nursing is like a key that opens so many doors," Lott says. "You can have so many different professions in nursing because there are so many specialties and so many career options."

Day one at Agape,

- early morning

It's 7:15 a.m. Two old but well-polished wooden pews set up in the hall of the Agape Clinic are filled with about two dozen adults, many accompanied by children. These are the people in society who are hidden in plain sight -- those who keep hotel rooms fresh and tidy, mop hospital corridors late into the night and serve busy families at fast-food restaurants. Many work for outsourcing companies that provide no benefits. Even if benefits are offered, most workers cannot afford the deductions from their paychecks. Inside the clinic, Kemp delivers his final pep talk, telling the class members they must give up being nursing students today. No longer dependent, they must be in charge.

"Everybody's always nervous, I'm always nervous the first week," says Kemp, adding that students have been known to choose another clinical after the shock of the initiation day at Agape. Since beginning this clinical rotation, Kemp has ushered more than 400 students through it.

"I think we'll be working today," Nooruddin says at 7:30 a.m. as the long line of patients files through the door. Kemp estimates the clinic can see 30 patients a day with its current staff and volunteers, and double that on Thursdays when the nursing students are working at top speed. Kemp's wife, Leslie, runs the triage desk in the waiting room. She identifies patients whose needs are most urgent, helps those who qualify get public aid and sets up referrals. The clinic also is open half-days on Friday and Saturday, the traditional day for Grace United volunteers. Agape is the only clinic in Dallas open year-round on Saturday for free school immunizations -- a boon to working families.

Maria Guadalupe "Lupe" Springer, the promotora whose position is partially funded by the Aetna Foundation grant, provides translation help and spiritual care, including a life-problems support group. Springer, a member of the nearby Emanuel Lutheran Church, began volunteering at Agape four years ago. She is the clinic's only full-time employee. Two registered nurse practitioners share the equivalent of another 1 positions with Leslie Kemp, although all put in many volunteer hours in addition to their paid ones.

By 7:45 a.m., four of the five exam rooms are full. Student Tammie Thai has just finished treating her first patient and is pleased. "I was writing notes on paper and Mr. Kemp said, 'No, write it on the chart.' I feel like they want to make me ready to be on my own," she says. Kemp moves through the exam rooms and crowded hallway as easily as he would his own home. He has spent his career providing medical care for the underserved and introducing the value of it to the Nursing School's students. Now in his 15th year on the Baylor faculty, he can be a bit philosophical: "When I teach, I create a space where we have all these people who are teaching the students, the patients, the volunteers. Leslie shows students the justice. Nobody ever goes away empty-handed. They're always affirmed as people," he says. "People at least deserve to have their illnesses treated, to at least have them looked at." It's a philosophy championed by the clinic's 11-member board of directors that includes Kemp and Barbara Stark Baxter, MD, the physician who started the Agape Clinic in 1983.

Kay Dial, a Baylor Nursing School alumna (BSN '87, MSN '02), who serves as the Agape nurse practitioner every Thursday, says the clinic's purpose exemplifies Baylor University's mission. "The thrust is on serving underprivileged or underserved populations, whether at home or abroad. Service to the underserved is more an emphasis in our program than in others," she says.

At 9:15 a.m., the clinic is getting warmer despite its basement location. The waiting room is filling up, and the hum of the floor fans only slightly tempers the noise of the crowded area. A bottleneck is stressing the staff in the exam area -- some patients have been waiting in exam rooms for more than half an hour. Nooruddin, whose job as back boss is to manage traffic flow, assesses the situation. "It wouldn't hurt to know Spanish; it would speed things up," she says. "Most exams are being delayed because we only have one person to interpret." She looks toward the waiting room and wonders aloud if she can ask the nonmedical community volunteers out front to interpret. Making her decision, she heads to the waiting area and returns with a second interpreter. The pace in the back office

picks up. In front, the line of patients now is out the door. There are several children undergoing required physicals for Head Start, the federally funded preschool program for at-risk students. Adult patients are moved through checks for weight, diabetes and vision, crisscrossing the tiny hallway that connects the exam rooms. At the far end is a pharmacy counter where student Matt Powers, who plans to become a helicopter flight nurse, is helping the nurse practitioner provide instructions for taking medication. The clinic orders generic drugs through a clearinghouse that supplies missionaries. It depends on local physicians to donate drug company samples of newer, more expensive pharmaceuticals. On a normal day with the students' help, the clinic staff will see up to 70 patients and provide an average of two prescriptions to each of them -- medication to which most of these patients otherwise never would have access, Kemp says.

- Mid-morning

"Lunes, martes, miércoles ... ." Nurse practitioner Dial is in the hall near the pharmacy counter showing Hurt how to write the days of the week on a medicine container for an elderly Hispanic patient. A few paces away, student Mindy Rhodes learns how to read the results of a urinalysis dipstick rather than depend on the machine -- a useful skill on medical missions and here at La Clinica Iglesia, which has just one machine. Also in the hall, Kemp is showing another student how to use duct tape to remove warts, a process he describes as slow but effective. Once taught, the student rushes off to a treatment room to show her patient. It's 9:45 a.m. The students have done two Head Start physicals and treated four patients with diabetes, a woman with bronchitis and a patient with athlete's foot.

They also see a nearly full-term pregnant woman who couldn't afford $50 for a prenatal visit elsewhere. The students are doing well. A routine assessment by Hurt identified a murmur in the carotid artery of a 63-year-old woman brought in by her family. The condition, called a carotid bruit, indicates a partial blockage of the artery that carries blood to the brain. A beaming Kemp stops his student in the hall and says, "You diagnosed your first bruit! If they do what we told them, then she won't have a stroke."

Nikki Burba detected a significant heart murmur in a child who came in for a Head Start physical. Kemp praised her for her thoroughness. Hurt completes an evaluation for scoliosis (curvature of the spine) and then moves to her next patient, an elderly woman. As the patient is ushered into exam room No. 2, Nooruddin silently mouths to Hurt, "Does not speak English."

The patient was discovered by students in a previous class during a neighborhood outreach visit, and Kemp has followed her medical situation closely. When first contacted by the nursing students going door to door, she just had arrived in the United States from Mexico to be reunited with her husband -- a pushcart ice-cream vendor -- after a 20-year separation. Students helped find furniture donations for the couple's home.

Kemp, who is bilingual but prefers to work with a translator, speaks quietly to the woman as he examines her foot and students crowd the doorway to observe. Her soles are covered with what look like thick patches of corn bread. Kemp treats her with great respect as he explains the condition -- chronic psoriasis -- to the students. It is controlled with high-potency steroid cream prescribed by a dermatologist who volunteers at the clinic on Saturdays, but the patient ran out of the cream three days ago. Kemp tells the students he'll consult with the dermatologist about the patient's chronic use of steroids.

Next, all patients, staff and students -- except those in the exam rooms -- gather around Chris Wynn, a student from nearby Dallas Theological Seminary (DTS), for the daily prayer circle. Wynn is serving his last day as clinic chaplain through a program coordinated by Common Grace Ministries, a community volunteer group. Chris' wife, Kara, another DTS student, is due back in two days from missionary work at a Rwanda hospital for people with HIV. "Thank you, Lord, for medicines and for justice in a world with injustice," Wynn says during a long prayer that is translated by Springer, whom Kemp considers the spiritual center of the clinic.

"I think we're doing good," Kemp says, turning from spiritual care back to practical care.

- Late morning

Now that the triage line is thinning and most of the patients have taken chairs in the waiting room, Hurt and Nooruddin switch jobs on their own initiative so that Nooruddin can do some assessments. Kramer is at the reception desk going through patient charts to record all the diagnoses and treatment decisions on the sign-in log. Although she has done paperwork all morning, she understands its importance because she did clerical work at an optometrist's office one summer. "The student in me wants to learn the skills and do assessments, but I know that this job is really important, too."

She doesn't stay at her desk, though. With the last patient checked in, she picks up a blood pressure cuff and goes through the waiting room offering checks to family members of patients.

Meanwhile, Nooruddin sees a middle-aged woman whose many health problems include diabetes and poor kidney function, a diagnosis she received from Dial last week at the clinic. She needs more specialized care but is reluctant to pursue it. Nooruddin consults with Kemp in the hall, and he tells her, "We have to say, 'Sorry, you must go back to Parkland (Memorial Hospital).' The gravity of the situation has been explained to the patient. She wants us to give her a different answer. We just don't have it." Kemp closes the chart decisively, adding that his wife will call ahead to Parkland to make it easier when the patient reaches the Ambulatory Care Clinic. Nooruddin bravely returns to tell her patient. After a few minutes, she walks the woman out to the waiting room, providing compassion when treatment falls short.

- Closing hour

It's 1:30 p.m., the clinic is beginning to clear out and Kramer is renewing her assault on the mountain of paperwork. The clinic closes in an hour, and when it does, the staff and students will have provided medical attention for 42 patients.

Kemp surveys the day's work and his eyes fall on student Tara Thompson, who is on her knees giving Head Start vision tests to two preschoolers at once. He smiles and says, "I don't think you'd call any of these students dependent now."