A Credible Witness

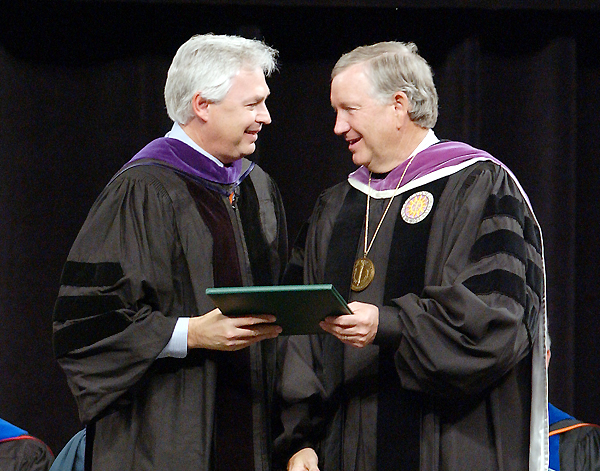

William D. Underwood, Baylor's interim president, is the son of a Baptist preacher. It could be said both father and son are in professions that inspire beleaguered souls to seek divine intervention. The younger Underwood does so as the unrelenting taskmaster of Baylor Law School's notoriously rigorous practice court, where he and fellow faculty member Gerald Powell, the Abner V. McCall Professor of Evidence, rule supreme over third-year law students. They have one charge: "Make lawyers out of them." And they do, in a masterful teaching duet of good cop/bad cop. Underwood, 48, a successful and respected attorney, knows how to play both -- a skill that may prove useful after he sets up office in Pat Neff as Baylor's chief executive officer. As he tells his students, a lawyer without credibility can achieve nothing, and he knows it also is true for him in this new position. " I cannot do anything that will ever cost me my credibility. I've got to be honest, I want to be direct with people, and you're going to find me to be remarkably open and transparent for whatever period of time I'm in this position." In the weeks between his April 29 appointment by the Board of Regents as interim-president elect and his assumption of duties June 1, Underwood spent hours meeting with and listening to many who care deeply about Baylor. He has been doing that for the past six months, and what he has heard encourages him. "I have spent a lot of time talking to folks, and what I'm hearing is a lot of the same thing, a lot of the same aspirations for the University, a lot of the same ideas about what Baylor ought to be," Underwood says. "I am surprised by how much common ground I really think there is. I think we have focused so much on our differences that we have forgotten there is a tremendous amount of agreement." Nevertheless, he inherited from outgoing President Robert B. Sloan Jr. a sharply divided faculty and a strained relationship between the former administration and the Baylor Alumni Association. Within days of his appointment, Underwood had met with the leadership of both groups. "I think taking problems to the people most affected by the problems and asking them to help solve the problem is something that I believe in," he says, a method he employed often when he served as Baylor's General Counsel in 1997-98 -- his only previous administrative role at the University. "It's a process that has worked well." Just three days after the regents' meeting, Underwood met with the Faculty Senate, an advisory body of 34 elected-at-large faculty that represents the University's 700-plus faculty members. The senators have been vocally critical of Sloan's leadership in the past two years, but at the end of Underwood's presentation, they gave him a standing ovation. "My message to them is there's a place at the table at Baylor University for lots of different people with lots of different gifts and lots of different talents," Underwood says. "I wanted folks who maybe felt like they weren't a part of 2012 to understand that they're a critically important ingredient to the future success of this University, and they're going to be recognized as such." Underwood says it is those who carry heavier teaching loads who enable the research, reflection and writing of others. "Without them, we can't get there. They're central to the success of what we're aspiring to do," he says. "And they're just as valued to me as the people who are being given the reduced teaching loads. Both of those groups of people have critical roles to play in the future of the University." The man who publicly debated Provost David Lyle Jeffrey last October about academic freedom says that issue meshes with Baylor's goal of integrating faith and learning. "I believe there are lots of different ways to support the mission of the University, lots of way to integrate your faith into the learning process here at Baylor," Underwood says. "How you choose to do it is, in my view, an academic freedom issue. I want to send that message to the Faculty Senate." Diversity of expression in academic freedom includes religious diversity, Underwood says. He values Baylor's "legal right" and privilege as a private institution to debate difficult societal issues in the classroom from a Christian perspective -- something no other Big 12 school can do. "That's a strength, that's something that makes the learning environment here fuller than it might be elsewhere, and it's something that we ought to encourage," he says. "At the same time, that's not the only way or necessarily for some people and some courses the best way to do it." A point of contention among faculty in recent years has been the method by which faculty candidates are interviewed by senior administration. Many have said candidates are questioned too vigorously about personal faith beliefs and how faith would be integrated in the classroom. Underwood says he thinks it's a matter of how it should be done rather than if it should be done. "I think that the hiring process is important to maintaining the Christian character of the University," he says. "You can't hire people who are hostile to our faith. You can't hire people, in my view, and expect them to integrate faith and learning who don't know anything about our faith." Underwood continues to seek input on the appropriate degree and depth of questioning during the interview process. He believes strongly, though, that a university should be "a marketplace for ideas," and wants to assure that such an environment is protected at Baylor. As interim president, Underwood plans to meet with the executive committee of the Faculty Senate weekly and set up meetings with groups of younger faculty members, many of whom he doesn't yet know well. While he attends to on-campus concerns, Underwood also will address the rocky relationship among some groups of alumni. The former administration's decision to begin an alumni department and a University magazine in summer 2002 generated hard feelings within the Baylor Alumni Association. The University contended that the BAA, an independent, dues-paying entity, could not generate the funds necessary to adequately serve the expanding needs of Baylor's 100,000 alumni. Underwood has been invited to meet with several groups of alumni, and he says he looks forward to doing so. He also has met with leadership of the Alumni Association and its board of directors. "I want to meet with some people who have been in leadership of the Friends of Baylor and of the Committee to Restore Integrity to Baylor organization as well," Underwood says. The two groups formed during the last two years, primarily pitted against each other over Baylor 2012 and Sloan's leadership. "I already know a lot of these people, and I want to continue talking with them." "I'm a big believer in communication," Underwood says. "I'm a big believer in telling people what I think, I'm a big believer in listening to what they have to say -- and I mean really listening to them -- because I know I've been wrong on enough occasions that I need to hear people. I'd just as soon be told I'm going to make a mistake before I make it than after." Underwood says most people he has talked with agree on the aspirations of 2012. The disagreement, he says, has been over methods of implementation. "Everybody understands now that the University was too ambitious in the number of faculty that were hired up front. And that has created a great deal of financial difficulty early on in 2012." The University's 2005-06 operating budget, approved by the regents in April, is in the black, and the numbers for the freshman fall 2005 class have surpassed expectations -- excellent news for a university funded primarily by tuition. Baylor will meet its budget, Underwood says, "because of the sacrifices of our faculty and staff [who received no raises in 2004-05]. It's not going to be because of any great thing we have done. I think it will be appropriate and necessary for us to let them know we appreciate it." Although he has no idea how long he'll serve as interim, Underwood is clear about one responsibility of a university president. "I think it's a critical responsibility of anyone in my position to go out and get the faculty the tools they need to succeed. I think that's what the faculty looks to the administration for. Imperative 12 [raising a $2 billion endowment] is an incredibly important imperative," he says. Consequently, he plans to be active in friend- and fundraising during his term as interim. "We will have to increase the resources available. The tuition increases have produced a tremendous amount of revenue for the University, but I think we have to do more on the development front than we have." Underwood is a man who has little, if anything, left to prove in his career, so why take on this challenge at this time? In an interview last November, he spoke of his feelings about Baylor and its importance: "I think Baylor has been perhaps the single most important institution to the people of the state of Texas that there has been. When I think about Baylor, I think about a virtual army of schoolteachers, of preachers, of choir directors, of doctors, of nurses, of lawyers, of businesspeople, of journalists spread all across this state having a positive influence in their communities day in and day out. I think that everybody at Baylor needs to remember how important this institution is and has been and needs to keep that in mind." Is that why he accepted the role of interim? "Yes," he says. "I think bringing people back together is something that can occur. I can't do it, but the Baylor family can do it. My sense is that there are a lot of people who want to see that happen, who want to get it done. I think we can, together, get that done."