To The Ends Of The Earth And Back

After traveling 95,000 miles across six continents and through 65 countries, David Stalcup found himself and his BMW motorcycle in Northeast Russia in the city of Yakutsk. His destination was Magadan, the former Stalin-era prison colony located at the end of the Russian time zone in Siberia. The only problem was how to get there. "You can't go to Magadan, there's no road to Magadan," people told him when he asked about passage. What he found was what had been a road, stretching more than 900 miles between Yakutsk and Magadan. It is known as the Road of Bones because of the bodies of captives who died on their way to the infamous prison. "The road is narrow," Stalcup says. "It's a swamp on both sides with giant bodies of water. The first one I went through, the water came completely up to the gas tank." At some points, he had to chop down trees and tie them together to form a bridge. He encountered flooding, smugglers and freezing snow before he made it to Magadan -- literally "the end of the earth."

Appropriately, it was the last leg of a globe-spanning journey that had taken the 2003 Baylor grad from his hometown of Lubbock, Texas, across South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, Australia and North America, most of it on motorcycle. He missed a boat to Antarctica by one week. The journey began in spring 1997, when Stalcup was in his last semester as a mathematics major at Baylor. "I was tired of looking at chalkboards," he says, so he decided to travel to Terra del Fuego, the southern tip of South America. He bought a BMW R-100 motorcycle, and dissembled and reassembled it in his apartment so he would know exactly how it worked. In December 1997, he crossed the border into Mexico and began what he thought would be a three-month adventure.

Within a few weeks, Mexico gave way to Guatemala, and Stalcup discovered a new passion in mountain climbing. He scaled all the tallest mountains through Central America, and ultimately four of the Seven Summits of the world. From Central America, he went into South America and soaked up as many cultural experiences as he could. He explored ancient Peruvian mountain settlements, camped on the Galapagos Islands and attended the Carnivale celebration in Brazil -- which he calls "the party of all parties." He played polo on a ranch in Brazil, danced the tango in Argentina and learned Spanish and later Russian. "I felt like I had learned and read a lot in college," he says, "but that I'd never really touched or experienced anything. I think it's very important for us to look outside the box."

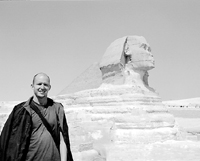

He crossed the deserts of Peru, into Bolivia and through Argentina. Because he carried all of his belongings on his motorcycle, Stalcup had to get creative with packing: "Sort of like Noah, I brought two of everything." He washed his clothes by hand and carried a small bottle of detergent. His tall frame presented other challenges. "There's not a shop in Mexico that's going to have clothes for a 6-foot-4-inch guy," he says, "so you have to buy your clothes in America and bring them with you." He camped often, stayed in 30-cent hotels occasionally and ate for about 50 cents or less a day. He managed on money he had earned and invested from a lawn business he had as a youth: "I hit the stock market right when it was booming." The appeal of the open road was contagious, he says, and his trip extended into nearly two years. Stalcup's next goal was Africa. After flying into Cape Town -- his bike in cargo -- he journeyed north toward Ethiopia and Sudan. Along the way, he experienced one of nature's most fascinating occurrences. "One of the greatest times I had in Africa was chasing wildebeests. I got there when the great migration was going on, and I rode along with them. It's the greatest rush I've ever had." He had other adrenaline rushes during his travels -- those caused by fear. In his five years, he says he was mugged, robbed and often had to deal with corrupt police systems. "You understand in a different way what it means to be a minority when you're the only tall white guy in a country," he says. But he also will tell you about the little African boy who came to his aid when Stalcup's motorcycle broke down in a blinding rainstorm, offering to take the stranger to his family's hut. "That was the beauty of it," he says. "You never knew what was going to happen the next day, something totally different and bizarre. It's total exposure." At the borders of Sudan, Stalcup received an unusually warm reception from the border patrol. "They told me, 'It's not every day we see an American.' I asked them how long it had been, and they said, 'Ten years. And, never one on a motorcycle.'" He went to Egypt, Israel and then took a boat to Greece. On his way to St. Petersburg and Moscow, he passed through all eight Russian time zones and some abandoned Soviet Air Force bases that had "the eeriest ghost-town feeling," he says. "The bases are completely deserted and stripped out, but you feel like people are still watching you." He spent seven days driving through Chechnya into Kyrgyzstan. At night, he camped in the bushes and stared up into an unending sky. "You have the whole sky," he says. "There's not one single light source out there. It's the most beautiful setting." As winter set in, Stalcup turned to South Asia. He went through China and Tibet (storing his bike and traveling by train), Kashmir, India and Mongolia. Trekking through the mountains in Nepal, he decided to go to the Taj Mahal. "I didn't want to die without seeing [it], and the Taj Mahal was right there," he says. "It is breathtaking as the sun rises across the river, lighting the baths, pools and inner sanctuary with a misty glow. "That's how this whole thing started," he says. "When you're that close to something and it only costs 50 bucks to get there, you gotta do it. You'll never have that chance again in your life." He tried to absorb and understand as much as possible about the different perspectives he encountered. "I got to see my reflection bounced off of every nation," he says, referring to being an American and a Christian. "I had to be a self-contained entity. People can lie to you, rob you, cheat you, but as long as you have something inside of you, they can't harm you." After traveling through Indonesia, Vietnam and Cambodia, Stalcup decided to go back into Russia and finish his odyssey in the port city of Magadan. The Road of Bones brought him to the edge of Siberia, where he boarded a plane and flew to Alaska. He rode through Canada and California and arrived back in Lubbock in late December 2002. He returned to Baylor that spring and completed his bachelor's degree in May 2003. Stalcup says of his travels that he "just wanted to do something adventurous and fun." Today, he's teaching math review courses in Lubbock and writing about his travels. "Everyone thinks it's a party for five years, but that's not always the case. There are a lot of tough situations where you have to be highly creative and clever," he says. And although he missed his family and friends -- he kept in touch through e-mail when it was available -- and would occasionally think about giving up and going back to America, those feelings never lasted long. "I'd get motivated and come back to my goal," he says. "I had to keep my eyes ahead, and while I was only taking small steps, at least I was going somewhere."

Christianson, BA '04, graduated in May from the professional writing program, where he specialized in screenwriting. He interned for Baylor Magazine during the spring semester.