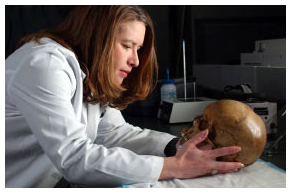

The Bone Collector

These days, it is not unusual for Lori Baker, assistant professor of anthropology, to have four or five interviews with the media in a single week. Since the start of her unique DNA identification program, "Reuniting Families," she has received calls from national radio, TV and print media interested in the humanitarian emphasis behind the scientific data.

The project, which Baker, BA '93, MA '94, developed after joining the Baylor faculty in fall 2002, seeks to identify bodies of immigrants who were trying to cross the Mexico border into the United States. It is an effort to bring closure to families who are looking for lost loved ones -- those who set out for the States with high hopes, and then disappeared. Her husband, Erich Baker, assistant professor of computer science, created a database -- www.reunitingfamilies.org -- that lists identifying traits of bodies found. It centralizes the DNA analysis done by Lori Baker and the information on bodies already found by county offices around the nation. Those looking for a lost relative on the database can do so anonymously. If there is a potential match, a DNA sample from the relative is compared to one from the remains. The first successful identification -- a woman -- was made last summer.

Baker will begin exhumations of some unknown graves this summer and visit counties along the border that are dealing with this problem. The University's 426 forensic science majors and 70 anthropology majors also have opportunities to be involved.

With the help of University Development, Baker, who funds her own travel related to the project, is applying for funding of $800,000 to $1 million from foundations. Baylor provides equipment and the facility, she says.

Last September, National Geographic's "Ultimate Explorer" filmed her working at Baylor's O'Grady Laboratory, about one mile northeast of campus, and at a paupers' cemetery in Tucson, Ariz. "It gave me a lot of confidence that what we're doing is worthwhile," she says. In this interview, Baker talks about her motivation for starting the project, where it is headed and why she considers it to be a culmination of her academic study.

Q & A

How did "Reuniting Families" begin at Baylor?

When I was a student here, Dr. Susan Wallace did a case down in the [Rio Grande] Valley. That's when we first became aware that there was an issue with individuals who were going unidentified because they were illegally in the U.S.

While working on my PhD, I started doing human rights work in Panama, Peru and Guatemala and started learning how we can use forensics to do identification of unknowns. When I came and talked with the Baylor administration and told them I was interested in doing this project, they were really supportive.

What does the project mean to you?

There are a lot of different reasons I started the project, one of which is my grandmother. During the Depression, her family was made up of migrant workers. Most of the people who come here do labor jobs, and a majority actually are migrant workers. I identify with these families, knowing the level of education my grandmother's family had at the time, knowing that trying to find a loved one would have been so incredibly difficult.

Also, I've spent my life praying about what I need to be, trying to decide my reason for living. When I was a child, I thought I was supposed to be a missionary. I came to college, and then I thought I was supposed to be an anthropologist. I started doing work around the world, and it just all came together in this project. I thought, "This is what my training is for." My whole life has been leading up to this being my vocation, teaching students and making them aware that there are human rights issues, which they can make a difference in, and using my abilities to make a difference in people's lives.

What is your reaction to the media's interest in the project?

I'm really surprised. I thought we might get a little local attention and get people involved because it's something that everybody knows is a problem. But it's one thing to know you have a problem; to know what to do about it is a whole other issue. It's hard to be working for a group of people that some feel animosity toward. It's a real shame because, in this situation, most of the [immigrants] ... are coming here to work. They don't feel that they can support their families. They don't feel like they have a lot of other options, so they're taking their lives into their own hands.

Why is this project important?

I talk to so many families, and they tell me it's hard because they assume -- after a certain amount of time not hearing from their family member -- that he or she must have died, and yet they don't know. They say that closure is so important, that having a place to go and grieve is important.

How are your students involved?

They'll be learning archaeological and forensic techniques, how to do an exhumation, collect evidence. Then we'll go into the analysis process -- how to determine age, sex, ethnicity and stature from skeletal remains. We'll have another group helping with DNA analysis. While I'll actually be doing the official DNA analysis, we'll still have them do the process with me, and we'll compare the results and see if they get the right results.

Why did you decide to return to Baylor?

I had a really good experience here as an undergraduate, doing field research around the world with my professors and doing research in the lab. I love being involved at an institution where you can actually interact with students, get them excited. When I came for my interview, I was really impressed with the leadership. A lot of universities don't have a vision for the future, and Baylor actually not only has a vision, but publicly states that vision.