Envisioning the Future

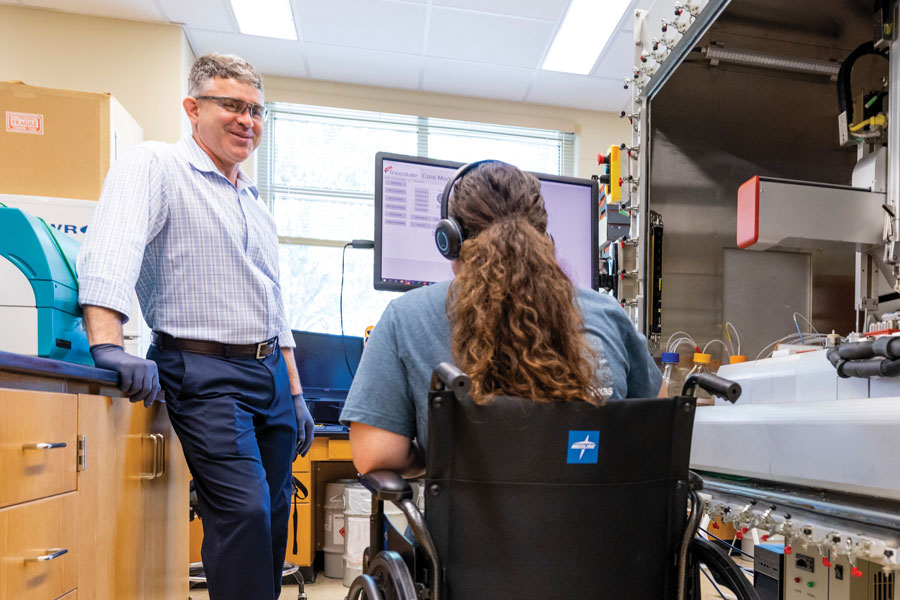

Biochemist Bryan Shaw and his team of researchers are pursuing advances that make laboratory spaces more accessible to those with different abilities.

Since joining the Baylor faculty in 2010, chemistry and biochemistry professor Bryan Shaw, Ph.D., has built a dual-track research career. As a bio-inorganic chemist, he studies changes in the properties of proteins and the effects they have on disease development, but that’s not what he’s best known for. “Nobody ever really cares about the science,” he laughs, because at the same time, he’s developing methods and tools to increase accessibility in science labs around the globe.

His accessibility research has been featured countless times in national media outlets such as NPR, NBC, the prestigious journal Science Advances, Texas Monthly and many other major publications — but the recognition is not what drives him. His accolades, awards and grants come second to the true purpose behind his work — human flourishing.

“I’m a chemist, and I do see myself in the human flourishing business,” Shaw said. “All the problems I work on, from the fundamental ones to the applied ones in chemistry, are related to human disease. For me, it’s not always about doing traditional chemistry, but also focusing on making labs accessible. There’s the regular chemistry we do, which we care so much about because we’re learning about the deep mysteries of the world. But once you help someone out in a way nobody else ever has before by creating a product that helps them … that becomes so addicting.”

“Children with blindness are typically put in a corner very early in terms of science education, and they’re excluded systemically from chemistry.”

Shaw’s work to make science accessible became even more personal after his son, Noah, was diagnosed with retinoblastoma as an infant in 2008. Shaw worked with Baylor Professor Greg Hamerly on a team to develop an app that parents and doctors can use to detect signs of the rare pediatric eye disease in their own children, aiding in early diagnosis and intervention. “I asked one of my son’s doctors once, Dr. Shizuo Mukai, about what Noah’s prognosis would have been if we had brought Noah in earlier, at 12 days when we first noticed symptoms,” Shaw said. “Dr. Mukai expressed that the tumors would have likely been so small in size and number that his right eye might have been salvaged, and radiation might not have been needed on his left eye.” Noah survived the treatment, but his sight was significantly impacted.

As Noah has grown up, Shaw’s scientific focus has grown with him. In addition to his lab’s research on proteins and the development of ALS, he has continued to seek ways to support those with blindness and other disabilities. He and his team have produced various methods to display scientific data in three dimensions so that students with optical impairments can feel the exact same information that sighted students are seeing.

In 2022, he was awarded a $1.3 million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health. This grant is funding the first effort to combine high-tech resources with low-tech “lab hacks” to make science concepts and laboratories accessible to students with blindness or low vision.

Opening New Doors for Science Education

The sciences have long been fields unavailable to students with blindness and other physical or intellectual limitations. Like other educators, Shaw recognizes the importance of eliminating implicit bias in academic settings that prevents students from equal access. But particularly in chemistry, there also exists an explicit bias that has purposely kept students with blindness out of the lab due to a lack of non-visual educational materials and technologies not yet optimized for those with optical impairments.

However, an understanding of chemistry is a critical foundation for anyone who desires to study in other fields such as biology, physics, engineering, medicine and even areas of law. Denying students an education in chemistry significantly limits their academic and professional pursuits. Making the chemistry lab totally accessible will open up a multitude of doors for people who have historically been kept out of these fields.

“Children with blindness are typically put in a corner very early in terms of science education, and they’re excluded systemically from chemistry,” Shaw said. “Some of the reasons for exclusion are safety concerns or because the lab has been designed only for people with eyesight. But much of chemistry and its technology can be modified for people with blindness and other limitations.”

Because, truly, who has ever even seen a molecule anyway? Their size is below the diffraction limit of visible light, which means they cannot be seen with the naked eye. Chemists have always developed tools to be able to visualize concepts that cannot be seen. Assistive technology, such as the microscope, is critical to the study of chemistry, even for sighted people. With rapid advances in technology, science labs are becoming more automated. Many tools that are already being implemented to help sighted people do their work more effectively can also help people with blindness.

Understanding and Producing Data

Shaw started his accessibility work by creating ways for students with blindness to understand existing data produced by sighted scientists. He and his team have developed various 3D modeling tools so that blind students can visualize and comprehend the same results that sighted students can see. He’s adopted the use of lithophanes — very thin slices of material that, when etched or engraved, allow light to pass through. When lit from behind, the image is visible. Since lithophanes are three-dimensional renderings, those with limited vision can also feel the image in three dimensions. Sighted and non-sighted people can observe the exact same data using the exact same tool.

“I follow a universal design approach to use the exact same curriculum, the exact same material to teach everyone, sighted or blind, at the same time,” Shaw said. Now he wants to make lab equipment and processes accessible as well, so that blind students can not only receive scientific data but also produce it.

Levi Garza, a second-year doctoral candidate in Shaw’s lab, has led the team to develop a tool they’re calling a Zampoña. Named in honor of Garza’s Hispanic heritage after the Spanish word for a pan flute, the Zampoña allows students with blindness to perform SDS-PAGE, a procedure that separates proteins based on their molecular masses and is widely used for a variety of applications across scientific disciplines.

Until now, SDS-PAGE was a process challenging for sighted people and impossible for those with blindness. It uses a pipette inserted into thin wells to transfer various liquid substrates and relies entirely on one’s ability to see that the pipette has been fully inserted into the correct channel. Garza’s Zampoña changes all that by allowing blind scientists to use their tactile sense to load the SDS-PAGE gels into the correct well.

“SDS-PAGE is the most common laboratory task in all of the life sciences. Everybody who works in life sciences is doing it, and it’s impossible to do if you’re blind. We have made it possible for those with blindness,” Shaw said. “Blind high schoolers, blind undergrads, blind postdocs and adults with Ph.Ds. who develop blindness later in life have used the Zampoña to load gels successfully, and the results they produce are identical to the results a sighted trained biochemist would produce.”

“This isn’t something that’s niche in our lab,” Garza added. “We’re making things for everybody that are very commonly used all over the world.” Hopefully, the Zampoña will become as commonplace in labs as the paper clip or the manila folder in the office.

Getting a Feel for Science

Last fall, Shaw’s lab hosted a cohort of high school students from the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired in Austin for a two-day event called “In Your Element.” As part of the NIH grant, the goal of this trip was to give these students the opportunity for interactive experiences in an operational university science lab with tools and processes designed for them.

Shaw’s team designed experiments that allowed the TSBVI students to conduct a variety of high-tech and low-tech laboratory procedures using lab equipment, including a robot that measures, pours and mixes chemicals. They learned about esters — chemical compounds that create distinct smells. They even got to try SDS-PAGE for themselves by loading their own gels — with and without the Zampoña.

“We had them do the technique without the Zampoña, and, as expected, it was a disaster,” Shaw recollected. “No results were produced. They weren’t able to do it. Then we gave them the Zampoña, and they did it perfectly.”

They were then able to feel the results of their procedure on the lithophanes.

“It felt very surreal,” Emma Olech, a 14-year-old TSBVI student, said. “It was amazing how simple it was, especially after doing it without the Zampoña.”

Dr. Mona Minkara, a bioengineering professor at Northeastern University in Boston, joined the TSBVI students during their visit to Baylor.

“I’ve been blind since I was a kid, and all I wanted to do was be a scientist,” Minkara said. “And all I heard was that I couldn’t be a scientist. So, to get to the point where we’re training the next generation to have the option to choose science? I can’t even describe to you in words how that hits me.”

“We could not make a model that would ever come close to the actual experience that they’re able to gather here in this program, with the mentors from Baylor,” said Neely Kulhanek, a teaching assistant at TSBVI. “I think as a culture, our attitude toward people with disabilities has grown so much, and Baylor is ahead of the game — a forefront type of program to be an example for others.”

As a result of their visit to the lab, TSBVI students participated in chemistry in ways that they hadn’t experienced before. For several of them, their interest in science was kindled, and they discovered new possibilities. Having the opportunity to explore the lab, experience scientific procedures and use lab equipment has been life-changing.

Science and Faith

Shaw arrived at Baylor in 2010, when Noah was 2 years old. He was looking for a place where his Christian faith would not just be tolerated but could inform his work. Coming from mainstream academic environments at UCLA and then Harvard, Shaw has always been “the Christian guy” in the lab. Shaw came to Baylor in part because of the Christian mission.

“I came to Baylor because, like a lot of people, I saw what a wonderful environment they’ve built for people to do science. I want to make a world in the lab where everyone can participate,” he said. “As my son gets older, and I meet other parents of children with disabilities, thinking about them when they’re in their 30s and 40s and what they’ll be doing is what keeps me up at night. Because what they’ll be doing in their 30s and 40s depends upon what they’re doing now, and what we’re doing for them. Most scientists are too busy, too into their own work to care. But at Baylor, it’s not that way. The people here care.”

“I want to make a world in the lab where everyone can participate.”

Garza, too, was drawn to Baylor because of his faith. “I was looking for an environment that coincided with my Christian beliefs and values,” Garza said, and he believes he found it at Baylor. “From the research team that I work with to the people that I pass by every single day, they’re all amazing. Baylor truly exemplifies a Christian university atmosphere.”

The accessibility research produced by Shaw’s lab team — which, in addition to Garza, includes Emily Alonzo, Mayte Gonzalez, Travis Lato, Darren Armstrong, Morgan Green, Chinthaka Fernando, Soeun Park, Matthew Guberman-Pfeffer and Noah Cook — has been widely recognized. They’ve partnered with researchers at universities across the nation who have co-authored many of these studies. Shaw and his team often encounter other scholars who are surprised, to say the least, by their Christian ethics. s

“We sometimes encounter scholars who don’t see any connection between our Christian faith and our research,” Shaw said. “They think our Christianity contradicts the science, but there is no conflict between science and faith. Any conflict is a human creation, and, history shows, temporary. I believe God made everything in this universe to be discoverable. God lets us discover everything about the universe and ourselves through hypothesis-driven research.”

“It’s a huge misconception that you choose either one or the other,” Garza said. “I think it’s both. Christianity and science go hand in hand. Science is the study of God’s beauty and His creation. And that’s what drives us and allows us to do the work that we do. The more that we understand these things, the more we can appreciate God’s creation. We can use science to help people — and that is our duty as Christians — to go the extra mile for people that may need it, like making chemistry accessible to all people.”

“Everybody knows somebody who might have a disability that’s keeping them from doing exactly what they want to do,” Shaw said. “I teach Sunday school, and there’s a girl in my class with Down syndrome. When I go to Memorial Hall for lunch, I might see a person with Down syndrome cleaning the tables. I go to H-E-B, and my groceries are bagged sometimes by a person with Down syndrome. I go to a coffee shop downtown where someone with Down syndrome is the barista who makes my coffee. Basically, everywhere I go, except the science lab, I encounter people with Down syndrome. We know that diverse groups of scientists — people who think differently because they live differently — produce better science. So, we will be going through the lab one piece at a time. You don’t have to be an expert in occupational therapy, or disability studies, or even science, to make the world around you accessible — to build ramps where there are stairs.”